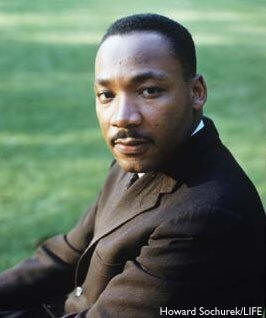

What Would Dr. King Make Of Hyper-Incarcertion in the 21st Century?

In 1964, a year after the March on Washington and four years before Dr. King was assassinated, there were 81,099 Americans in prison. 27,191 were black. In 2009, there were 1,613,656 prisoners in America. Over 600,000 were black. Over 2.3 million people are locked up in prisons and jails in the U.S. and over 850,000 of these are black. Sociologist Lawrence Bobo explains that “[t]he rise of mass incarceration has had a disproportionate effect on African-American communities, especially those that are low-income.” He adds that “[w]e are at a point where 1 in 15 black men is in jail or prison – and for those between the ages of 20-34, the rate is 1 in 9.”

As one of the most important moral voices of last century, Dr. King spoke of racial and economic justice. He cared deeply about human rights. What would he have to say about America’s prison boom and particularly its destructive effects on poor people in general and poor blacks in particular?

I looked back at some of his words for guidance and offer the following excerpts from Why We Can’t Wait published in 1964 for your consideration:

“Jailing the Negro was once as much of a threat as the loss of a job. To any Negro who displayed a spark of manhood, a southern law-enforcement officer could say: “Nigger, watch your step, or I’ll put you in jail.” The Negro knew what going to jail meant. It meant not only confinement and isolation from his loved ones. It meant that at the jailhouse he could probably expect a severe beating. And it meant that his day in court, if he had it, would be a mockery of justice.”

This excerpt is incredibly rich and ripe for analysis. Dr. King links the jailing of black people in his era with the State’s abiding interest in emasculating black men.

What type of threat does incarceration pose for black people in 2011? Rose Brewer and Nancy Heitzeg (2008) make the case that “[t]he post-civil rights era explosion in criminalization and incarceration is fundamentally a project in racialization and macro injustice.” Michelle Alexander calls it the “New Jim Crow.” These writers and researchers suggest that hyper or mass incarceration has emerged in part as an “indirect mechanism for perpetuating systemic racism.” Recently Bill Quigley advanced fourteen examples of racism in the criminal justice system. These examples support the case made by scholars and social commentators that what we are currently experiencing in the 21st century is as Loic Wacquant has characterized it “a new fourth state of racial oppression.”

Even today there still exists in the South — and in certain areas of the North — the license that our society allows to unjust officials who implement their authority in the name of justice to practice injustice against minorities. Where, in the days of slavery, social license and custom placed the unbridled power of the whip in the hands of overseers and masters, today — especially in the southern half of the nation — armies of officials are clothed in uniform, invested with authority, armed with the instruments of violence and death and conditioned to believe that they can intimidate, maim or kill Negroes with the same recklessness that once motivated the slaveowner. If one doubts this conclusion, let him search the records and find how rarely in any southern state a police officer has been punished for abusing a Negro. (King, 1964)

Dr. King references the history of slavery and posits its critical import in understanding black people’s relationship to the criminal legal system. He explains black people’s inherent mistrust of law enforcement as having its roots in slavery and in Jim Crow. The words quoted above have as much relevance in 2011 as when they were first written by Dr. King in 1963. One only needs to think of Sean Bell, Oscar Grant, and the countless nameless and faceless young people of color who are subjected to the whims of the punishing state and its implementers (police, court personnel, etc…) to grasp the relevance for today.

Since nonviolent action has entered the scene, however, the white man has gasped at a new phenomenon. He has seen Negroes, by the hundreds and by the thousands, marching toward him, knowing they are going to jail, wanting to go to jail, willing to accept the confinement, willing to risk the beatings and the uncertain justice of the southern courts.

There were no more powerful moments in the Birmingham episode than during the closing days in the campaign, when Negro youngsters ran after white policemen, asking to be locked up. There was an element of unmalicious mischief in this. The Negro youngsters, although perfectly willing to submit to imprisonment, knew that we had already filled up the jails, and that the police had no place left to take them.

When, for decades, you have been able to make a man compromise his manhood by threatening him with a cruel and unjust punishment, and when suddenly he turns upon you and says: “Punish me. I do not deserve it. But because I do not deserve it, I will accept it so that the world will know that I am right and you are wrong,” you hardly know what to do. You feel defeated and secretly ashamed. You know that this man is as good a man as you are; that from some mysterious source he has found the courage and the conviction to meet physical force with soul force.(King, 1964)

It frankly seems quaint to recall how mass protests for racial and economic justice occurred not that long ago with people who were hoping to be arrested and locked up. Their level of commitment to the cause of social justice was that strong. It is difficult to believe that thousands of people in 2011 would mobilize in this same way to address the injustice of mass incarceration. Yet it is something to strive for.

So it was that, to the Negro, going to jail was no longer a disgrace but a badge of honor. The Revolution of the Negro not only attacked the external cause of his misery, but revealed him to himself. He was somebody. He had a sense of somebodiness. He was impatient to be free. (King, 1964, pp.26-30)

There is a certain perverseness to the words above as we consider them in 2011. What we know today is that for some young black boys in particular going to prison has become a more common experience than going to college, joining a union, or doing military service. These young people are not there as resisters in the classic sense. They are the unwilling fodder for an insatiable punishing state that is looking to disappear them. The outstanding question is whether people of color and in particular black people in 2011 are ready to organize a large-scale movement to dismantle the prison industrial complex. The jury is still out on this. It has been written that for Dr.King social justice would not “roll in on the wings of inevitability” but would come through struggle and sacrifice. One would imagine that he would exhort us all today to struggle and sacrifice in order to dismantle the unjust and destructive racial caste system that is a by-product of hyper or mass incarceration. Happy Birthday, Dr. King and thank you! I leave everyone with these powerful words by Dr. King.