What Should We Make Of Prison Tourism?

Defunct prisons all over the world operate as tourist attractions, museums and even hostels, offering everything from haunted tours to the chance to stay overnight in a cell. Even more surprisingly, some old prisons are being used as wedding sites.

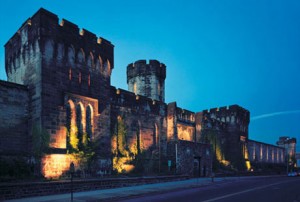

Alcatraz was opened to tourists by the National Park Service in 1971. Today over a million people visit the island prison each year. What meanings do people who visit Alcatraz and other prisons like Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia as tourists bring to and take away from their visits?

Some tourists undoubtedly visit old prisons because of an interest in architecture. Many of these defunct facilities were built at a certain period of time in American history and are formidable and imposing structures. Other tourists surely visit because they are fascinated with the stories of crime and “criminals” that they can hear about. These stories play the same role as the scary camp fire tales that some people remember from their youth. Still others might visit because they have an interest in the history of the United States and therefore would want to learn more about our history of punishment and social control. Michelle Brown (2009) explains that “[v]isitors arrive at the gates of closed prisons for many reasons — to retrace history, to search for ghosts, and to view otherwise prohibited places (p.90).” She adds: “Still, most have trouble articulating why they are visiting at all (p.90).” This point is an interesting one to ponder because it challenges us to interrogate our human fascination with disaster and pain.

So far, I have exclusively addressed tourism in defunct/closed prisons. There are also tourists who visit working prisons. In these cases, the prisons and the prisoners act as “living museums (Brown 2009, p.90). I am unsure if it is the same population that visits both of these types of sites: the defunct and the working prison. One would imagine that at least some of the people who are visiting working prisons today as tourists are doing so for research and informational purposes. Though Brown (2009) contends that this is “the minority of most tourists at these sites (p.91).” I will not be concerned with tours of working prisons in this post. I hope to come back to that topic in the future.

Prison tourism is not a new thing. When U.S. prisons were first opened in the 19th century, they were often the largest and most imposing structures in cities and towns. People would visit just to marvel at the impressive structures and no doubt to satisfy their curiosity about the prisoners who inhabited these places as well. Famous writers and intellectuals like Alexis de Tocqueville and Charles Dickens also made such visits to American prisons during that time.

Michelle Brown (2009) writes:

“These early ambassadors and diplomats spent days and sometimes weeks in the study of the prisons they visited, talking openly with administrators, staff, and inmates, observing daily operations, and writing about the experience in correspondance, notes, and eventually key works, citing the American prison project as a crucial democratic experiment in governance and the production of civic life (p.94).”

What I am concerned with here though is the modern phenomenon of prison tourism. Today, we lack public intellectuals of the stature of De Tocqueville and Dickens who are regularly visiting and writing about prisons. Most of the modern prison tourists are there in the role of spectators and consumers of pain and punishment. As such, I want to highlight some information about the complexities of modern prison tourism.

Michelle Brown (2009) describes a series of prison tours that she took in her book “The Culture of Punishment: Prison, Society, and Spectacle.” I was struck by this particular passage in the book that captures the inherent commercialism of these tours:

“At the gates of the prison, sally ports and administrative offices are converted into ticket desks and souvenir shops. This staging area is carefully arranged with both historical materials – signs, brochures, pamphlets, photos, posters, books, and plaques describing and commemorating the history and function of the institution as well as consumer spectacle – magnets, key chains, coffee mugs, shot glasses, T-shirts, playing cards, postcards, Hollywood souvenirs, disposable cameras, and ghost hunting equipment (flashlights, dowsing rods, etc.). At the Ohio State Reformatory and the former West Virginia Penitentiary, these discourses intersect as friends and families take photos of one another standing beside the electric chair or weapons display cases of homemade prisoner shanks and shivs. At West Virginia Penitentiary, some pose for the camera in areas designed to simulate mug shots. The entrance to prison tours consequently sets the stage for how to treat the event, emphasizing the tour as both museum and theme park – an experience to be carefully documented through the accumulation of a visual record (photos/postcards) and the purchase of souvenirs. (p.100)”

The excerpt quoted above really underscores how prison tours try to engage participants in both history and commerce at once. In some of these tours, there is also an emphasis in recounting the gruesomeness of certain crimes and in sensationalizing criminal exploits. Here again, I quote from Brown:

“Stops are made along the way at various points where stabbings, assaults, rapes, and murders occurred. These are some of the most descriptive and prolonged moments of the guided tours where escorts engage in complex narrative constructions, much like a good ghost story, emphasizing at the conclusion that all of this took place ‘right where we are standing.’ These flashpoints are also highlighted in publicity materials. At West Virginia Penitentiary, tourists are encouraged to ‘visit North Hall, where the most violent criminals spent 22 out of 24 hours,’ to ‘witness, Old Sparky which was built by an inmate to execute inmates,’ and to ‘see Charlie Manson’s letter requesting transfer to Moundsville.’ (p.106)”

Brown (2009) explains that “[t]his format lends legitimacy and authenticity to the experience, acting not only as a basic primer in institutional functions, in how inmates were housed and processed on a daily basis, but also engaging in and reproducing popular constructions and stereotypes of criminality, deviance, and danger. (p.106)”

So you might ask what’s the point in considering prison tourism?

What, if anything, is wrong with people touring defunct/closed prisons? I started thinking seriously about this issue a couple of years ago when I considered taking a trip to visit Alcatraz. When I do visit prisons, they are always working ones and I am almost always there to visit a particular person. I haven’t visited closed prisons as a tourist. I have found myself over the years uncomfortable with the idea of prison tourism and I never could put my finger on the reasons until a few months ago when I read Michelle Brown’s book.

Brown (2009) writes: “In most prison touring contexts, all human life with any direct connection to the practice of punishment is omitted.” Here is where my discomfort with this practice becomes acute. How can we think about prison without thinking about the incarcerated bodies that make up its core? The answer, I think, is that we cannot and should not lest we offer a fantastical view of prisons and how they work. This leads me to believe that prison tourism actually harms the possibility of organizing for the ultimate abolition of all prisons. These tours, rather than serving as a way to convert people into budding prison reformers, are actually more likely to distance the public from the actual realities of prison life by sensationalizing the carceral experience and by othering the prisoner. The tourist acts mostly as a detached spectator who might as well be watching an episode of Lockup, USA on regular television. Prison tourism then turns people into voyeurs of the incarceration experience rather than potential allies for transforming the current system.

For those readers who have visited defunct/closed prisons, what led you to do so? What did you learn? Am I wrong in my assessment?

Update: Thanks to Mary for sending along this youtube video of a tour at the West Virginia Penitentiary which partly illustrates what I wrote about here.