Out of the Mouths of Babes: Ten Questions Often Asked by Children Whose Parents Are In Prison

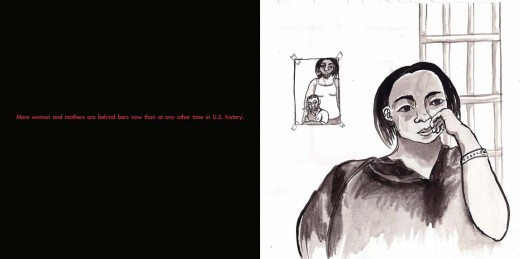

I was sent a book called “What Will Happen to Me?” this week. It is about children whose parents are incarcerated. The first thing that struck me were the 30 color photographic portraits of beautiful children that are featured throughout the book . The pictures are poignant and affecting. These are all of our children. Along with the photographs, we can read the children’s thoughts and reflections about their experience of having a parent in prison. One young woman’s portrait particularly called out to me. Her name is Maranda and she looks just like my little sister did as a child. Here is the text that accompanies her photograph:

“I would be thinking about my mom before I went to sleep. I had a counselor, but I didn’t talk to her. I just talked to her about problems with my friends ’cause I don’t like spreading that around about my mom. It makes me sad. It felt good when my mom came back. And when my dad comes back, I want to take him out to eat and go swimming and do other things. Go to the movies.”

From her comments, it seems that both of her parents are behind bars. It is incomprehensible to me that this could be the case but it seems that it is. It is truly tragic. Her words belie the simple pleasures that so many children yearn for: going swimming and to the movies with their parents. Yet what also comes across is Maranda sense of shame; shame that she has a mother in prison. This is an emotion that I know many other children with incarcerated parents experience. It is our failure as a society to provide these children with love and compassion that feeds the shame.

The main thing that I appreciate about the book is that it moves beyond the statistics (which are of course important) and tells the human stories about the impact of incarceration on family members. The book underscores the very real collateral costs of incarceration. I dare anyone to look at the faces of the children portrayed in this book and not be convinced that what we are currently doing to millions of people through mass incarceration is inhumane and immoral.

The book also shares the stories and thoughts of grandparents who are drafted into service to become caregivers for their grandchildren as a result of parental incarceration. “What Will Happen to Me?” includes information for family members, educators, social workers, clergy and other community members about how to support children to deal with their emotions and how to access needed resources. The book is co-authored by Howard Zehr (he is also the photographer) who is world renowned as a restorative justice practitioner. As such, the book includes a “Children’s Bill of Rights” along with thoughtful consideration about how to apply restorative justice and respect for relationships in these difficult situations.

Below is an excerpt from the book that might be of interest:

Ten Questions Often Asked By Children Whose Parents Are In Prison

By Howard Zehr and Lorraine Stutzman Amstutz,

Author of “What Will Happen To Me?”Children need time to adjust to the separation caused by having a parent in prison. But it takes more than time. As we have heard in their voices, children also need to make sense of what has happened to them and to their parent or parents. Because of this, they have many questions.

Some of the questions they ask are straightforward. But sometimes their questions come out indirectly or in their challenging behavior. Incarcerated parents, as well as caregivers of children or other adults in their lives, often have to answer their uncomfortable questions.

Children who are present when a parent is arrested, especially young children, are usually not told where their parents are being taken, when they will be coming home, or why they have to go away. As time goes on, the children have even more questions.

Our childhood experiences shape much of our adult lives. Children who live with these kinds of questions, many of which are not answered to their satisfaction, experience trauma as a result. Frequently that leads to their general mistrust of authority, especially the legal system. Not having their questions answered can also lead children to blame themselves for their parents’ absence or to believe that they are destined to follow in their parents’ footsteps.

Here are questions that children whose parents are incarcerated often ask, along with suggestions about how to answer them. We will address some of the questions more fully in later sections of the book.

1) Where is my Mom or Dad?

Parents and caregivers often believe it is best to protect children by not telling them where their mothers or fathers really are. Children may be told that their parents are working in another state, going to school, or serving in the military. Sometimes children are told that their parents are ill and had to go away for special treatment.Sooner or later children will realize the truth and know they have been lied to. This tends to hurt their relationship with the persons who have told them the untrue stories and can lead to feelings of distrust that affect their other relationships as well.

While the adult who hides painful reality does so believing it is in the best interest of the child, such an action (or inaction) creates a family secret that results in children feeling ashamed. Most childhood experts advise that children be told the truth.

2) When is he or she coming home?

The outcome and schedule of a parent’s arrest and/or imprisonment is often uncertain. However, it is important to keep children up-to-date about what parents or caregivers do know. Children need to have concrete information they can deal with, even if it is, “We don’t know what will happen yet.”3) Why is she or he in jail or prison?

Sometimes an innocent person is arrested. But when a parent has done wrong, it is important that this wrongdoing is acknowledged. Children need to know that there are consequences when people do things that are against the law or harmful to others.At the same time, they also need to be reassured that even if someone sometimes does something wrong, it doesn’t mean that s/he is necessarily a bad person. While a child’s parent may be serving the consequences for something wrong s/he did, the parent is still worthy of love and capable of loving.

A child can learn to trust a caregiver who is honest about what a parent has done wrong. This practice of honesty allows the child to believe other things that the caregiver tells her or him as they progress together on this journey.

4) Can I talk to my mom or dad?

Jails and prisons have specific and often constraining rules about prisoners talking on the phone to their loved ones. Phone calls from prison are often quite expensive and restricted in length. Many times a parent does not have enough money to call home because it is so expensive.When phone calls are difficult, letters can be especially important. Although young children may find it hard to express themselves through words, they may find it more meaningful to make drawings. As Stacy Bouchet, now an adult, suggests in her reflections, children often treasure the notes and letters they receive from their parents, as she did from her father.

5) When can I see my mom or dad?

It is helpful to explain to children that prisons have specific times for visiting, and their caretakers will get that information so that they can see their loved ones. If a parent is incarcerated at a distance, the child should be prepared for seeing his or her mother or father infrequently.Some children are angry and do not want to see their parents, or at least they’re ambivalent about the possibility. In general, though, it seems important for children to visit their parents as regularly as possible.

Before the first visit, they should be prepared for the circumstances of the visit. The caregiver should explain the security around the prison. The children should also know that there will be limits upon where they can visit and what they can do with their parents.

Most children want to know what their parent’s life is like in prison. They may imagine frightening scenarios. Giving them a sense of mundane details of everyday life in prison can be helpful. If the child is interested, a caregiver can encourage the parent to describe his or her cell or room and tell what a normal day is like.

6) Who is going to take care of me?

Children in this situation often feel insecure. It is important to let children know who will be caring for them. If there is uncertainty about their living arrangements, children may need to be told that, but they also need to be reassured that plans for their care are being made and that they will not be abandoned. As much as possible, they need stability in their living situations and their relationships.7) Do my parents still love me?

When children are separated from their parents, they often worry about whether their parents love and care for them. Most children need reassurance that they are loved by their parents no matter where the children happen to be living and with whom. They also value other loving relationships in their lives, but they still want to know about their parents’ interest and love.8. Is this my fault?

Children often blame themselves for being separated from their parents or even for their parents’ misbehavior. They may imagine that if they had behaved better their parents would still be with them. They need reassurance on three fronts: that what happened to their loved one is not their fault, that it happened because that person did something wrong or harmful, and that this does not mean that their parent is a bad person.9) Why do I feel so sad and angry?

Sadness and anger are children’s common responses to a parent’s incarceration. But most children do not understand their feelings or the origins of them. It is helpful for them to be reassured that their feelings are normal. Ideally, they can be encouraged to talk about their feelings of sadness or anger. If they cannot talk to their immediate caregivers such as their grandparents, they can be invited to talk to school counselors or social workers or even friends. Children often find it helpful to know other children in similar situations because they can understand each other’s feelings. Children who find it hard to articulate their feelings can be encouraged to express them through their drawings or other art work.10) Can I do something to help?

Children typically feel helpless and responsible. They need to know that their loved ones usually appreciate letters and pictures. They can be encouraged to send them as often as they want to.

The above is an excerpt from the book “What Will Happen To Me?“ by Howard Zehr and Lorraine Stutzman Amstutz. The above excerpt is a digitally scanned reproduction of text from print. Although this excerpt has been proofread, occasional errors may appear due to the scanning process. Please refer to the finished book for accuracy.For more information please visit http://www.howardzehr.com/ and follow the author on Facebook

Reprinted from What Will Happen to Me?. © by Good Books (www.GoodBooks.com). Used by permission. All rights reserved.

It is well worth your time to read this book and even better if you give a copy of it to your school social workers, your children’s teachers, and others who might regularly interact with young people. In case you are wondering if I get a cut of the book profits, unfortunately I do not. I still recommend the book. 🙂