Jon Burge, Torture, and the Militarization of the Police

While some people are only now waking up to the connections between the military and the PIC, this has been a trend for decades.

Julilly Kohler-Hausmann has written a terrific chapter titled “Militarizing the Police: Officer Jon Burge, Torture, and War in the ‘Urban Jungle’” which appears in Stephen Hartnett’s edited volume Challenging the Prison Industrial Complex.

Hausmann suggests that: “Americans, as domestic political unrest and the war in the jungles of Vietnam intensified during the late 1960s, increasingly referred to ‘urban jungles’ to organize their comments about the homefront (p.48).”

Furthermore, she adds important information to our understanding of the history of the militarization of law enforcement:

“Urban areas had long been constructed as foreign, racialized spaces; once they were in open revolt, their struggles with state authority were easily interpreted with the same rhetorical devices used for insurgent populations abroad. Thus, it is not surprising that over time, more and more voices called for the state to use the same tools and techniques employed overseas to subdue allegedly dangerous spaces. And so, by the mid-to-late 1960s, domestic law enforcement agencies had begun to interpret the conditions in inner cities as wars and had begun to turn for answers to military training, technology, and terminology (p. 48).”

A couple of weeks ago, I raised the point that some rappers in the 1980s and 1990s were likening their communities to “war zones” and the police to “an occupying force.” What I did not consider in that analysis is that this characterization pre-dated them. Hausmann quotes Inspector Daryl Gates of the LAPD as saying that “the streets of America had become foreign territory” during the 1965 Watts rebellions. It turns out that modern rappers were responding to the conditions in their communities engendered by a war that had been declared decades earlier by the state. Around the same time that Inspector Gates was making his comments about Watts, black nationalists and other activists were describing themselves as inhabiting “colonies” within the United States and being “occupied people.” Here is a quote cited by Hausmann from Black Panther David Hilliard in his autobiography illustrating this concept:

“we’re a colony, a people with a distinct culture who are used for cheap labor. The only difference between us, and, say, Algeria, is that we are inside the mother country. And the police have the same relation to us that the American Army does to Vietnam: they are a force of occupation which will stop at nothing to keep us under control.”

So interestingly, we had the representatives of state power and their targets reinforcing each others’ message that the inner city was “foreign territory.” Ironically by reinforcing the message that the “ghetto” was a war zone (which reflected the truth of their daily experiences in these communities), marginalized people were unintentionally watering the seeds of their own destruction and further oppression.

1968 brought a new opportunity for urban police forces to purchase new equipment and technologies thanks to funding from the passage of the Safe Streets Act. They also had license earned by the social anxiety and fear engendered by Vietnam and domestic urban rebellions to turn these new products on the marginalized population of the inner cities across America.

Jon Burge served in Vietnam in the late 1960s as a military police officer and was responsible for among other things transporting and guarding prisoners of war. Hausmann suggests that he would have observed some of the techniques employed by military intelligence officers who were interrogating prisoners. One of the tools that these intelligence officers used was a “field phone” as an instrument of torture. Hausmann writes:

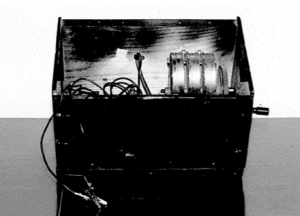

“Many also admitted that it was common for military intelligence officers to rig wires from hand-cranked field telephones to shock prisoners, ostensibly to extract confessions and information. But the use of field phones in torture was not limited to Vietnam, as the first reports of the device actually surfaced stateside, where it was allegedly assembled in the early 1960s by a doctor at the Tucker Prison Farm in Arkansas. Knowledge of this device, often called the “Tucker telephone,” migrated to Vietnam and references to its use have subsequently been reported all over the world (p.57).”

What is striking about this description of the field telephone is that it illustrates how technologies easily migrated between the U.S. to the war zone and back again.

Burge joined the Chicago Police Department in 1970 and was promoted a couple of years later to detective in Area 2. Hausmann tells us that “the first reports of abuse surfaced shortly after Burge joined the force; the Tucker telephone reappeared in 1973 when Burge used it to torture Anthony Holmes during an interrogation (p.57).”

Between 1972 and 1991, Jon Burge tortured or supervised the torture of more than 100 people (all except one were African American). The methods of torture were diverse, systematic and brutal; additionally the torture which was perpetrated by a group of white detectives who called themselves the “A-team” was always verbally laced with racial slurs:

“He and the detectives under him used a variety of techniques, including beatings, Russian roulette, shocking, and mock executions to coerce confessions from crime suspects; these techniques were intended to inflict high levels of pain or fear without leaving any physical evidence of violence; most of these forms of torture would be familiar to people knowledgeable about the unsanctioned but pervasive interrogation procedures employed by U.S. forces in Vietnam. On other occasions, victims were handcuffed to hot radiators, forced to strip, and repeatedly beaten on the genitals. Officers suffocated some detainees by placing a large bag or typewriter cover over their heads; Burge and his colleagues also shocked victims on the scrotum, penis, anus, fingers, or ears with a cattle prod or the field phone (p.57-58).”

You should all read Hausmann’s entire chapter for more information on the Chicago Police Torture cases and their connection to the militarization of police forces. Additionally, for more information about the cases, visit the site for the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, a terrific project that I am proud to be associated with.

Update: Thanks to reader Eric for flagging this story and sending it to me. It looks like just today the deaths of two black men in Area 2’s police station have been ruled “suicides.” Attorneys and supporters of these men’s families are invoking Burge and raising suspicions as to what really happened.