Watts 1965 and Some Thoughts About Police Violence…

Earlier this week, the 1965 Watts Rebellion came up in the context of a sociology class that I teach at a local university. Unsurprisingly many of my students knew little to nothing about the history of this police riot. For those who had heard of Watts, they only had very basic information about the incident. Almost no one knew of the central role that a militarized police force played in both inciting and then ultimately brutally repressing the rebellion.

Because of racist covenants, Blacks in Los Angeles were restricted to two main community areas: Watts was one of these. Poverty and unemployment were endemic in the community. Most of the businesses were run by outsiders and the majority did not employ community residents. These businesses were very much resented by locals. This fact would become important to understanding why so many local businesses were targeted during the uprising.

On the evening of August 11, 1965, 21 year old Marquette Frye was stopped by a white highway patrolman, named Lee Minikus, near Watts for driving erratically. The officer smelled liquor on his breath and told him to walk a straight line. According to the officer, Frye failed the test and was charged with driving under the influence. Officer Minikus began to write a ticket and Marquette started to argue that he should be let off without one. During this time, his stepbrother Ronald was a passenger in the car but when he saw that a tow truck was approaching to impound it, he stepped out and asked if he could drive the car to his mother’s house just a couple of blocks away. In the meantime, their mother, Mrs. Frye had heard about the incident from neighbors and arrived on the scene with her license and registration (the car was hers) asking the police not to impound the car. Officer Minikus agreed to let her take the car and then she began to admonish her son Marquette for being intoxicated. According to an account by historian Robert Conot, this is when things took a turn for the worse:

On the evening of August 11, 1965, 21 year old Marquette Frye was stopped by a white highway patrolman, named Lee Minikus, near Watts for driving erratically. The officer smelled liquor on his breath and told him to walk a straight line. According to the officer, Frye failed the test and was charged with driving under the influence. Officer Minikus began to write a ticket and Marquette started to argue that he should be let off without one. During this time, his stepbrother Ronald was a passenger in the car but when he saw that a tow truck was approaching to impound it, he stepped out and asked if he could drive the car to his mother’s house just a couple of blocks away. In the meantime, their mother, Mrs. Frye had heard about the incident from neighbors and arrived on the scene with her license and registration (the car was hers) asking the police not to impound the car. Officer Minikus agreed to let her take the car and then she began to admonish her son Marquette for being intoxicated. According to an account by historian Robert Conot, this is when things took a turn for the worse:

“Momma, I’m not going to jail. I’m not drunk and I’m not going to jail.”…As he spoke to his mother, his voice broke. He was almost crying. Spotting the officers [who were approaching], he started backing away, his feet shuffling, his arms waving…All his old anger, the old frustration, welled up within Marquette… What right did they have to treat him like this? [He screamed at the cops,] whipping his body about as if he were half boxer, half dancer…”

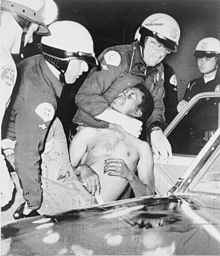

According to official accounts, the police made calls for reinforcements. One police officer used his nightstick and according to him accidentally hit Marquette Frye in the forehead causing his head to bleed. Ronald tried to protect his brother and was hit in the stomach. Minikus grabbed Marquette and threw him into a squad car. Mrs. Frye rushed to the aid of her sons and jumped onto Minikus’s back. She was restrained by other officers and also put into a police car. In the end, all three Fryes were under arrest.

It was a hot summer evening so many residents were outside their homes and witnessed the traffic stop and subsequent arrests. Within 10 minutes a crowd of 25 had grown to nearly 300. Within 20 minutes the crowd swelled to over 1000 people. One of the onlookers was a young student at Compton Junior College named Joyce Ann Gaines. She had run out of a nearby beauty salon so she still had on her smock. A police officer felt something on the back of his neck and decided that it was spit. He identified Gaines (who was innocent) as the culprit. She struggled against being removed from the crowd and arrested. One of her friends tried to intervene to help her and he was promptly put in a squad car too.

Tensions in the community were high to say the least. As the police finally retreated, they left behind an angry crowd. Rumors flew that the young woman, Joyce Gaines, who had been arrested was pregnant. People also said that the Fryes had been mistreated and abused during the incident This incident took place within the context of a community that was sick of constant police harassment. This was also a community fed up with living in dilapidated housing and angry about the ongoing racism that they were experiencing. The Frye incident was the spark but the anger and tension had been simmering for decades. The Watts Rebellion of 1965 lasted for seven days and it took a contingent of nearly 14,000 national guardsmen along with thousands of police officers to eventually quell the uprising. The rebellion resulted in 34 deaths, over a thousand injured and property damage in excess of $40 million dollars.

For an excellent account of the Watts uprising, I highly recommend Robert Conant’s book “Rivers of Blood, Years of Darkness.” To view a collection of photographs about Watts, click here.

Why does Watts matter in 2012? Well because as Malcolm X said: “Armed with the knowledge of our past, we can charter a course for our future.” Last year, I wrote that discussions about law enforcement’s brutality toward Occupy Movement participants were divorced from historical context. This is of great concern because I believe that it limits the effectiveness of social justice movements when we act as though everything old is new again. We should be learning from past experience to improve for the future. The lessons of the past should be informing our current strategies for social transformation. As thousands of people prepare to descend upon my city for Chicago Spring (G8/NATO Summits), I think that we have an opportunity to avoid the past mistakes in terms of our interactions with the police.

I have been and am currently working on a few projects that I hope will help to inform and educate the broader public about the longstanding tradition of oppressive policing toward marginalized populations (including some activists and organizers). One of the projects that I am most excited about is a series of pamphlets about historical moments of police violence. I reached out to some friends inviting them to contribute to the project. I am thrilled to say that several people have taken on the challenge of researching and writing one or two pamphlets (which will be no more than 30 pages each). Topics include: Oscar Grant, the 1937 Memorial Day Riots, Timothy Thomas, The Dixmoor Five, Mississippi Summer, The Danzinger Bridge Incident, the Young Lords, 1968 Democratic Convention, Black Protests on College Campuses, among others…

This idea is inspired by the many pamphlets (precursors to today’s zines) that circulated in the U.S. & in the developing world during the 1950s and 60s in particular. W.E.B. DuBois, CLR James and many other luminaries published short 10 to 30 page pamphlets about different political ideas and historical figures that would sell for as little as 15 or 25 cents. Many were also distributed free of charge. These were produced by companies like International Publishers out of New York or associations like the Afro-American Heritage Association here in Chicago. The goal is to revive this idea for the 21st century recognizing that it is important not to confine learning to classrooms and facilitated spaces. The pamphlets will be made available free of charge online and we hope to print a limited number of copies that can be mailed to currently incarcerated youth and adults.

The first couple of pamphlets will hopefully be published in May. We will continue to publish other pamphlets throughout the course of the year.