Parchman Farm and the Quelling of Black Protest

I write often on this blog about the intersections between the carceral state and the history of black protest. Today I want to continue that exploration by focusing on the history of the Mississippi State Penitentiary also known as Parchman Farm. The prison has been memorialized by the famous Bukka White song “Parchman Farm Blues.”

Mississippi Governor James Vardaman who was elected in 1903 was an avowed racist but also virulently against convict leasing. His critique was that the lease system enriched specific individuals at the expense of the state. He advanced a proposal to create a state-run penal farm which led to the establishment of Parchman Prison Farm in 1904. So Parchman Farm was conceived as a reform project. Instead, it became notorious as one of the most racist, violent, and brutal prisons in America.I will focus another day on the actual history of Parchman. Today, I will underscore the prison’s role as a tool to quell the dissent and protests of the Civil Rights movement. David Oshinsky (1996) writes that: “In the 1960s, Mississippi officials used the Delta prison to house — and break down — those who challenged its racist customs and segregation laws (p.233).”

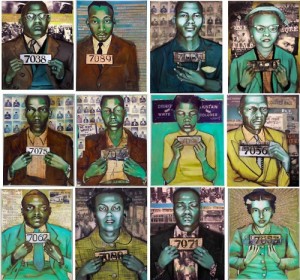

In the summer of 1961, hundreds Freedom Riders including James Farmer, James Bevel and Stokely Carmichael were imprisoned at Parchman. They had rejected paying a $200 fine and chose prison instead. This was part of the vaunted Jail No Bail strategy developed by SNCC. Considered troublemakers by prison administrators and many of the convicts at the State Penitentiary, the Freedom Riders were placed in sweltering cells in the maximum security section isolated from other prisoners. According to Oshinsky, “Governor Barnett left explicit instructions to keep the Freedom Riders safe. Break their spirit, he suggested, but not their bones (p.235).” Oshinsky describes how the Freedom Riders spent their days at Parchman:

In the summer of 1961, hundreds Freedom Riders including James Farmer, James Bevel and Stokely Carmichael were imprisoned at Parchman. They had rejected paying a $200 fine and chose prison instead. This was part of the vaunted Jail No Bail strategy developed by SNCC. Considered troublemakers by prison administrators and many of the convicts at the State Penitentiary, the Freedom Riders were placed in sweltering cells in the maximum security section isolated from other prisoners. According to Oshinsky, “Governor Barnett left explicit instructions to keep the Freedom Riders safe. Break their spirit, he suggested, but not their bones (p.235).” Oshinsky describes how the Freedom Riders spent their days at Parchman:

“Life was hard and monotonous for them, but the danger had passed. The protestors lived two to a cell in stifling eight-by-ten compartments, segregated by sex and race. They left only to shower twice a week. There was no fresh air or exercise time, no cigarettes or reading material except the Bible and a racist tract about the inferiority of blacks. The food was bug-ridden and drenched in salt. The women wore striped prison dresses, the men ill-fitting underwear…To ease the boredom, the Freedom Riders did calisthenics and sang freedom songs. Their loud, energetic voices grated on the guards, who warned them to pipe down. When the prisoners refused, their bedding was taken away. One of the memorable scenes from Parchman involved a tall, reed-thin Howard University student named Stokely Carmichael being dragged along the cell-block floor on his mattress, singing ‘I’m Gonna Tell God How You Treat Me.’ (p.235-236)”

After serving an average of 39 days at Parchman (some like Carmichael had spent 53 days there), the Freedom Riders were released. If you are interested in more about the history of Mississippi’s criminal legal system, I wrote a post about a year ago in response to the case of the Scott Sisters.