LGBTQ Youth, Violence & The Promise and Limits of Storytelling

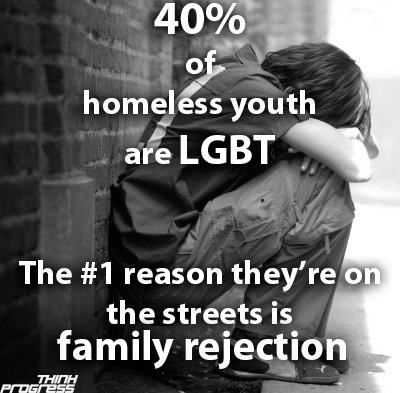

So this image has been making the rounds on social media over the past couple of weeks…

The photograph and words elicit an immediate emotional reaction from the audience. “How sad,” one might think. “What’s wrong with these horrible families?” another might ask. “We need to change our culture to make it more tolerant,” someone else might prescribe.

The photograph has engendered a lot of discussion in my circles. The image is meant to dramatize a recent study by the Williams Institute. The study is problematic on a number of levels and my very smart friends had a lot to say about it. I particularly appreciated the following commentary about the photograph by Facebook friend Johannah Westmacott:

“okay, so here’s what’s wrong with this picture: it’s not true.

sure, 40% of homeless youth in NYC self-identify as, and disclose being, LGBTQ, so the real numbers might be higher here. but NYC sees LGBTQ runaways from the rest of the country. numbers in other parts of the country suggest a 20-40% range.

but that’s not the part that concerns me about this meme. it’s absolutely not true that the #1 reason they’re on the street is family rejection. sure family rejection happens and it’s a serious problem, but so does a FAILED child welfare system (which is usually more conservative/homophobic/biphobic/transphobic than any family), poverty, institutional racism/sexism/classism/ableism/homophobia/biphobia/transphobia that affects landlords/teachers/employers/social workers/welfare workers, untreated mental illness, substance abuse, criminalization and criminal records, etc.

this “family rejection” line is dangerous because it completely absolves society and places 100% of the blame for youth homelessness on the families of origin. and i don’t support that.”

I write constantly on this blog about the propensity in our culture to reduce everything to the level of the individual. We have a profound inability to analyze the root causes of social problems because that would necessitate understanding structural oppression. Neoliberalism only exacerbates this tendency and serves to absolve society of its responsibility to provide equal opportunities for all.

Joe goes on to make another important point about the study:

“the researchers didn’t ask the YOUTH why they were experiencing homelessness, they asked service providers what they thought the leading causes of youth homelessness were.”

It is unfathomable to me that this fact is not prominently featured in all discussions and coverage of the study. There is nothing wrong with surveying “service providers” but this should be foregrounded. Too often, researchers bypass the experiences of young people, treating them more as props than as agents of their own lives.

Joe offered an example of LGBTQ young people (currently and formerly homeless) speaking for themselves and organizing around the issues that they see as most pressing in their lives. We must provide our most marginalized youth with the tools and opportunity to narrate their own experiences. The current and formerly homeless LGBTQ youth who produced the film below seem to prioritize their negative encounters with law enforcement as particularly deleterious.

I have mentioned before that my organization is currently engaged in a participatory action research project with young people about their daily encounters with the police. The project is called Chain Reaction: Alternatives to Calling the Police. As part of this work, we have partnered with LGBTQ youth in Chicago to record and discuss their experiences of criminalization. You can listen to some of their stories here. Rather than family violence, the stories that most of these young people share speak more to an unrelenting barrage of social forces that lock them into a disadvantaged position (without hope of escape).

I want to make it clear though that it is not enough to simply offer a forum or provide the tools for marginalized young people to share their “stories.” More is needed, those stories have to be historicized, theorized, and then deployed in the service of making social change. Narrated experiences still need context and analysis. I think that we should not shy away from that. In our Chain Reaction work for example, we are not simply content to let the experiences of the young people speak for themselves. Rather, we want to locate those experiences within a broader discussion about the forces of Neoliberalism which have helped to structure and produce the very negative outcomes that our young people are subjected to.

My friend Yasmin Nair has a lot of very intelligent things to say about the problematic nature of encouraging youth (particularly youth of color) to “perform” their oppression through things like spoken word. And you should read her thoughts about that here. But it is a line that she wrote about the politics of storytelling that I want to underscore today:

“Stories, the best kind, the kind that speak to whatever we might call truth should evoke context and the politics of the times in which they exist.”

Identifying “family rejection” as the #1 reason for why LGBTQ youth find themselves homeless is not neutral and it may not even be true. But promoting this as a “fact” has real world implications for how we go about trying “solve” the crisis. By telling a story about individual youth who are rejected by their intolerant (usually read to be black, brown and poor) families, we obscure the complicated social, economic, and political forces that are the root causes of homelessness for these youth. What gets lost is the racism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, ableism, etc… that is foundational to the problem. We must resist the erasure of these forces of oppression at all cost. We can begin by being very skeptical about images like the one that has been circulating so prominently on Facebook.