‘Taking Back BoysTown’ or How Some Queer Folk Can Be Hella Oppressive

I am incredibly lucky to be in community with some of the most brilliant people anywhere. One of those is my colleague and friend Owen Daniel-McCarter who is one of the founders of the Transformative Justice Law Project of Illinois. Owen recently published an excellent article and I want to share it with the readers of this blog. The article titled “Us vs. Them! Gays and the Criminalization of Queer Youth of Color in Chicago” is timely and will be particularly relevant to those who are interested in racism, classism, heterosexism, homophobia, and the criminalization of youth. I am only sharing a few excerpts from the article but you should really read it in its entirety HERE (PDF).

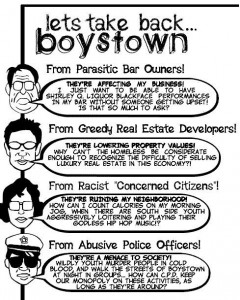

Owen offers some background for understanding the emergence of the “Take Back Boystown” phenomenon in Chicago:

After several publicly violent incidents in “Boystown” directly preceding and following the 2011 Chicago Pride Parade, residents of “Boystown” responded with calls for more policing, tougher enforcement of criminal laws, and resurrection of gang injunction ordinances. They even demanded that Chicago’s LGBT community center, the Center on Halsted, and a shelter for LGBT Youth known as the “Crib” be shut down for “attracting” violent outsiders into the “Boystown” community.” While “Boystown” residents’ fear of outside “invaders” seems to happen annually following the Pride Parade, this year was particularly hyper vigilant. Residents of “Boystown” created a facebook page called “Take Back Boystown” which touts to be “a venue for suggestions, ideas and thoughts on how we can preserve what we have and go back to the safe fun neighborhood Boystown is known for.” The site has provided a venue most notably for free-flowing rants from residents of “Boystown” about young people who are not residents of the neighborhood, referring to them in racialized code words such as “gangs,” “thugs,” and “hoodlums.” Local gay media immediately made the connection between public violence, youth, and race by reporting that “criminal activity” in “Boystown” could be due to the “presence of South and West Side youth.” As any resident of Chicago knows, “South and West Side youth” is code for Black and Latin@ youth.

Moved to action by the influx of young queer people from “other neighborhoods,” the Lake View Citizens’ Council introduced an online Petition to the Superintendent of the Chicago Police and the President of the Chicago Transit Authority that stated:

WHEREAS crime in the Lake View has been on the rise this year;

WHEREAS violent assaults have affected the livelihood of the residents of Lake View;

WHEREAS the crime committed comes from individuals NOT living in the Lake View area;

WHEREAS businesses in the area have felt the affects of the increase in crime and;

WHEREAS police in these areas have been deployed outside of the area;

THEREFORE we. the undersigned. who reside, work or have businesses in the Lake View Community AND PAY TAXES FOR CITY SERVICES demand from the Chicago Police Department an additional 20-30 police in the 19th and 23rd Districts of Lake View during the midnight-4am shift.

We also demand additional security canine patrol at the Belmont L stop during the same period of time.

IV.”This Work is Personal to Us-It is About Our Lives:” Liberatory Approaches

A liberatory approach to violence is one that “seeks safety and accountability without relying on alienation, punishment, or state or systemic violence, including incarceration and policing.” Thus, gay (and straight) residents of “Boystown” investing in increased policing, private policing, and harsh prosecution of queer youth of color “not from this neighborhood,” lacks a liberatory analysis. Many residents of “Boystown” argue that their property rights, the enjoyment of their neighborhood entertainment, and the privileges they have worked toward and donated to as gays are at stake with the “threat” of young people of color in their neighborhood. And, in some instances, physical violence and a threat of real physical violence has presented itself. All too often though, when the “victim” of interpersonal violence is a person of color, the violence is underreported or even accepted. As Kimberle Crenshaw argues, this downplaying of violence against people of color is a contemporary manifestation of racist narratives involving crime and violence with predetermined racial assumptions about who is “victim” and who is “perpetrator.” Regardless, it is without question that the people who are suffering the most due to “Take Back Boystown” movements are young people of color.

For true liberation the gay community in “Boystown” needs to reject the divisive “Us v. Them!” strategy and instead seek a transformative framework to help address the deep-seeded histories and current practices of anti-queer, anti-youth, and racist laws and policies in Chicago. This liberatory framework, then, must also include healing from violence and the internalized violence that systemic oppression manifests.

In her book, Democracy Remixed: Black Youth and the Future of American Politics, Cathy J. Cohen reveals the findings of the Black Youth Project, a groundbreaking survey asking young Black respondents living in America what they think about the government, their own lives and opportunities, their sexualities, etc. Considering the web of barriers to young Black people accessing so-called “opportunity,” it is not surprising that many have little to no faith in the ideology that the U.S. government aims to protect them. 61% of the Black youth surveyed believe that it is hard for young Black people to get ahead because they face so much discrimination. Further, nearly 80% of Black youth surveyed felt that the police discriminate more against Black youth than white youth. Cohen also reports that youth are aware that this is largely due to stigma about Black youth in general. She reiterates the response of one seventeen-year old Black young person who said “If [the police] see four or five black young dudes standing on the corner, we gotta be selling dope and stuff like that. So, they just already got us labeled.” She reveals that Black youth who experience overt discrimination, which is the majority of Black youth, have a profound disbelief in notions of “equal opportunity,” a disbelief that becomes more entrenched as they age. The connection between social alienation and so-called “deviance” is undeniable. Despite glaring social inequality for youth of color, “Boystown” residents, politicians, and business owners demand “[f]riendly, respectful social behavior,” not “anti-social, confrontational, and intimidating behavior.” Just as Richard Wright painted in his fictional Bigger Thomas, stigmatized and oppressed young Black people are both treated as though they are outside of society, and yet at the same time expected to behave with respect for the society that ostracizes them.

Youth who frequent “Boystown” have modeled many liberatory approaches in response to being labeled a threat to public spaces. As part of its “Street Youth Rise Up!” campaign, a campaign designed to change the way Chicago sees and treats its homeless, homefree, and street-based young people, youth from the Young Women's Empowerment Project wrote a bill of rights by and for young people living on the streets of Chicago. This includes “rights when accessing health care, interactions with the police, when working with social services agencies, and in education – places where queer youth of color experience pervasive institutionalized violence.” In addition to addressing rights for youth, this document also addresses action steps for others. For example, it states that “The police should receive trainings by youth or youth competent services providers on how to work with homeless, home free or street based young people in a respectful way and help them connect to voluntary and nonjudgmental services instead of arresting us.”‘ In conjunction with the release of this “Street Youth Bill of Rights,” youth marched through “Boystown” on September 30, 2011 to demand their basic needs be met and that there be accountability for the criminalization of their survival. The Street Youth Rise Up campaign is, at its very core, a liberatory movement led by youth of color that resists participation in state violence.

Similarly, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and allied youth of color from Gender JUST, an intergenerational multiracial organization based on Chicago’s South Side, orchestrated a number of protests to the push for increased policing in “Boystown” as a solution to violence in the community. Young people boldly stood up at the Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy meeting held on July 6, 2011 with nearly 800 people – mostly residents of “Boystown” – in attendance, stating “we see policing and profiling as tools of violence – and you can’t fight violence with violence.” In 2010, they also protested the Northalsted Business Alliance for supporting the policing of young people of color in “Boystown” neighborhood stores and at the Center on Halsted. In addition to protesting the policing of young people of color in “Boystown” public accommodations, they also launched the Committee on Urban Resource Sustainability & Equity (“COURSE”) campaign which aims to help solve another problem rooted in the “Take Back Boystown” movement: the lack of resources for queer people living on the South and West Sides of Chicago.[…]

Reflecting on the acute sense of abandonment she felt by the Gay Rights movement as a young criminalized transgender woman of color, Sylvia Rivera warned: “The oppressed becomes the oppressor.” A gay community politic that demands and even self-funds harsh policing of queer youth of color within a city, state, and country that oppresses youth, queers, and people of color at shocking rates is an oppressive politic. While many youth and adult allies are fighting for liberation, for now, gay residents, gay politicians, and gay business owners of “Boystown” are developing instruments of abuse, criminalization, and stigmatization against young queer people of color consistent with U.S. traditions of ageism, white supremacy, and institutionalized heterosexism. Queer youth in Chicago demand frameworks for liberatory political action that challenge the oppressive thinking of mainstream “gays” in “Boystown.” In their participatory action research report, youth from the Young Women’s Empowerment Project suggest concrete steps to end the systemic violence they experience that residents of “Boystown” must consider: “Think Critically about the law before advocating for a policy … [W]ill it just lead to an increase in police presence? Will removing a law decrease girls’ risk for violence or abuse?” Without asking these questions and grappling with their answers, liberatory dreams are lost.

Please read the whole article as these excerpts do not do Owen’s argument full justice.

Note: The following video provides some good context about “Take Back Boystown:”

My friend Sam Worley wrote an excellent article about the Battle in Boystown last year. I recommend it for those who want to learn more.