Deja Vu All Over Again: More Police in Public Schools…

Early last year, I was on WBEZ talking about a report that I co-authored titled “Policing Chicago Public Schools.” I discussed the fact that black students in Chicago Public Schools (CPS) are disproportionately arrested and recommended that we rely on restorative practices for addressing disciplinary issues instead.

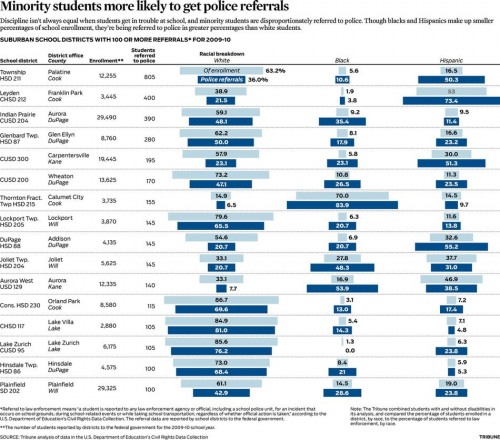

In CPS about 25 students a day are arrested on school property. The Chicago Tribune reports that in Illinois, minority students are disproportionately targeted for arrests. This is of course unsurprising. Below is a chart from their report:

We spend over $70 million on school security in CPS (with $25 million going to the Chicago Police Department to provide two police officers for each high school). In addition, last year, the Chicago Public Schools launched a Compstat “school-safety” partnership in order to further cement the ties between schools and law enforcement:

“The program brings police, principals and religious leaders together on a weekly basis to discuss crime and safety plans, analyze data and continually evaluate the implementation of those plans.”

On a local level, law enforcement is already embedded into the life of our schools. We have been working for years to break the overreliance of our schools on the police. Now comes word that President Obama is proposing a new pool of grant money so that school districts can hire more police. Specifically:

According to the White House, Obama plans on “using this year’s COPS program to provide incentives for more police departments to hire school resource officers” in addition to a “new, comprehensive school safety initiative to help local school districts hire up to 1,000 school resource officers and school-based mental health professionals, as well as make other investments in school safety.”

Over the years, “COPS has contributed nearly a billion dollars to hire more than 6,300 school resource officers (SROs) and expand the use of metal detectors and surveillance cameras in schools” across the country. It’s clear, however, that some have learned nothing since 1994 when the first iteration of this program passed under Bill Clinton. Bernardine Dohrn offers an important history lesson about the last time that gun-control reformers tried to make schools “safer:”

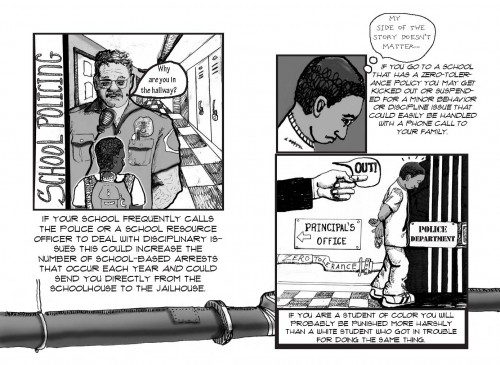

It was, after all, the well-meaning gun-control and youth advocates who drafted the now notorious zero-tolerance provisions into the federal Gun-Free Schools Act of 1994. It made mandatory a one-year expulsion (“exclusion”) from school for youth arrested for possession of firearms on school property – at pain of losing federal school funding. State legislatures rushed to comply with the mandate, and within a five-month period, legislation was passed in every state to place schools in compliance with the Safe Schools Act expulsion requirements, the quickest ever state compliance to maintain federal funding eligibility. One year later, the Safe Schools Act was amended, transforming the prohibition from possession of a “firearm” to possession of a “dangerous weapon,” and the door was pushed open for a stampede. A dangerous weapon was defined as “a weapon, device, instrument, material or substance, animate or inanimate, that is used for, or is readily capable of, causing death or serious bodily injury.” (18 USCA 930(g) (2) 1998. Weapons came to include a shoe, a foot, a book. The vast numbers of children and youth since arrested in and expelled from schools – in fact, deprived of an education – have been arrested or expelled for minor and non-weapon misbehaviors and have been disproportionally children of color and children with disabilities.

Importantly, the lessons of 1994 are not lost on all lawmakers. At a hearing about the school-to-prison pipeline just last month, Sen. Dick Durbin of my state had this to say:

“For many young people our schools are increasingly a gateway to the criminal justice system,” said Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) during a Senate subcommittee hearing in December that addressed the consequences of the school-to- prison pipeline. “What’s especially concerning about this phenomenon is that it deprives our kids of a fundamental right to education.”

It is my sincere hope and expectation that Sen. Durbin will be one of the vocal opponents of efforts to increase the number of police officers in schools.

The work that I do means that I am on the front lines of seeing the impact of the school-to-prison pipeline. Young people are often harmed by their interactions with police in schools. Minor disciplinary issues escalate and turn into arrests that can have a lifelong impact on young people’s lives. A couple of years ago, a young woman named “Mariah” who I’ve known for years was denied a nursing license after a background check turned up an arrest that had taken place in the 8th grade for a fight at school. She was not even referred to court for the incident and simply received an “informal station adjustment.” We had to spend several days to expunge her record and then send relevant paperwork to the state licensing agency. Thankfully, today she is working as a nurse practitioner. I wrote a series of posts about Mariah’s ordeal which you can read here, here, here, and here.

It’s also important to recognize that the already too close relationship between law enforcement and schools leaves youth vulnerable to be targeted for incidents that occur even outside of school hours. A young man in one of our programs narrated his experience of being pushed out of CPS. I hope that you will take a minute to listen to the audio.

I’ve been asked repeatedly what counter-proposal I would offer to the White House. It’s simple. Mass shootings are RARE. Schools are still the safest places for children and youth in the United States; safer than their homes and often their neighborhoods. We could improve the safety of our schools by REMOVING police officers from them. What our schools need are good teachers, sufficient counselors & social workers, updated books, an engaging curriculum, and a culture of calm. That’s it. Research suggests that police officers DO NOT make our schools safer. Those who say that they want to rely on data have a trove of it to choose from. Our goal needs to be to dismantle rather than exacerbate the school-to-prison pipeline.

Finally, the loudest and frankly ONLY voices that I have heard in the public sphere about this issue belong to adults. However, in my experience, young people across Chicago and the nation have very strong views about police officers in their schools. You can listen to some of what they have to say in these youth-created films. The following youth-created website “Suspension Stories” brings together resources (including reports, videos, images, audio, and curricula) about the school-to-prison pipeline. We already know what works to improve school safety and it doesn’t involve more police. Let’s instead devote ourselves to eradicating the greatest form of violence in the United States: POVERTY.