We Were Never Meant To Survive: On Quvenzhané Wallis, Intersectionality, & Drones…

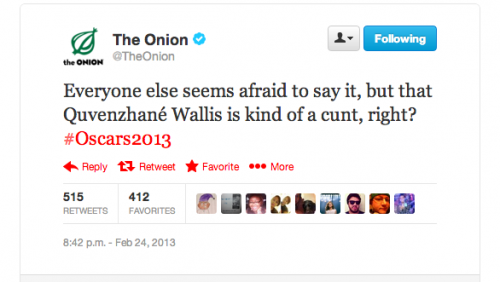

This was going to be a post about the roots of racism and their implications for organizing to end mass incarceration. Then I “watched” the Oscars on Twitter and saw a tweet by the Onion about 9 year old black actress, Quvenzhané Wallis:

My head exploded. I took to Twitter to rant about how disgusting I felt the Onion was to say such a vile thing about a child. I tried to stop there but then went on a tirade about the historical context for this sexual objectification of a black girl. I suggested that originating in slavery, the idea that black women are loose, promiscuous, and generally easygoing about sexual matters still circulates throughout the dominant American culture and has an impact on intra-racial and inter-racial gender and sexual politics.

Look, I am not dumb and I enjoy a good joke as much as anyone else. I understand that this was an attempt by the Onion to make fun of the way that actresses are talked about in the media. But I was deeply offended that they chose to pick on a 9-year old black girl in this way. I tried to take a couple of hours away from social media but still found it difficult to calm down. I am an insomniac but I was even more agitated than usual so I decided to write in greater depth about the sources of my anger and disappointment. My thoughts are inchoate and regular readers are used to this so here goes…

A study by MEE productions published in 2004 found that:

“Black females are dissed by almost everyone. Young African American females hold little status within their communities, reflected in the name-calling and devaluing of young girls. Not only do males not trust females, but overwhelmingly, girls reported that they do not even trust each other.”

This encapsulates the racialized misogyny that exists in our society and that is often internalized by black girls themselves. It’s not difficult to understand why the Onion would feel it OK to target a 9-year old black girl within this context.

Michelle Wallace (1990) put it best when speaking about African American women, we have “high visibility” combined with an “almost total lack of voice” (5). This seems like a contradiction and yet many black women can attest to the duality of being both black and female in a culture that devalues both of these identities. Jill Nelson (1997) writes powerfully about being both a visible and an invisible target of violence in a racist and sexist culture:

“Sometimes, there is the violence summoned by being visible to men as an objectified, sexualized thing. Lost in happy thought, a perfectly wonderful day is verbally assaulted because I did not hear a man speak to me, did not speak to him, or maybe I did hear him call, “Hey, mama with the big legs!” but chose not to respond. His violence toward me then is verbal, something along the lines of “Well, fuck you, bitch. Your legs aren’t shit, anyway.” What I’d like to say is, “No one asked you, dickhead,” but I don’t, feel in a desperate way as if I got over, escaped, because his violence was limited to words. I am torn between the desire to be seen, heard, and appreciated, and the tendency to cower within my black female invisibility, knowing that even though to be invisible is a constant source of pain and rage, to be noticed only as a representation of something men can use at will is far more dangerous (p.153-54).”

I found myself pleading for support from black men in particular last night. What I didn’t do was plead for empathy. Dr. Christina Sharpe writes that “in the US, domestic blackness rarely results in something like empathy.” She suggests that we are unable to structurally care about black bodies. I take this to heart. I expected that a number of people would dismiss the Onion’s tweet as “satire” or as a “joke.” They did. I expected that I would be accused of being overly sensitive. I was. I didn’t under any circumstance expect empathy for this black girl-child from the majority of people. I was right not to. In much the way that Beasts of the Southern Wild ends, in 21st century America, we leave far too many little black girls out in the world to fend for themselves, unprotected, undefended and unloved. We saw this play out in part last night on social media.

I’m doing research for a still-undefined project about lynching in America. I came across an editorial in the Meridian Clarion dated August 7, 1865 that stated:

“A hundred years is a long time to one man: but to a nation or a race, it is but a limited period. Well, in that time the negro will be dead. Slavery is abolished now, but in a hundred years the negro himself will be abolished. Nothing but the fiat of the Almighty can stay the hand of his fate…”

Reading this editorial felt like a punch in the gut. I paused a couple of times to catch my breath. I thought to myself (not for the first time): “We were never meant to survive.”

When slavery “ended,” black people were left to fend for ourselves. The South ceded the responsibility for the care of the former slaves to the North. You wanted them freed, they said. They are your problem now. In response, the North created the Freedmen’s Bureau which is mostly known today for the over 4,000 schools that it established across the South for black people. The Freedmen’s Bureau had very limited resources and delivered these in a capricious fashion.

Former black slaves were destitute after the war. They were left hungry, without employment, without an education, without housing, and without even shoes. As “free” men and women,they continued to be punished with new laws intended to re-enslave them and with brutality intended to control or kill them. Many white people believed that blacks could not and would not survive outside of slavery (as the Clarion editorial illustrates).

But the “freed” slaves persisted and they did what they had to do to ensure their survival. They were branded as lazy and as criminal. If the newly freed slaves did in fact steal, it was a derivative crime born out of the fact that they had been abandoned and were still being exploited for their labor. In Virginia, a group of black tobacco workers complained in 1868 [transcribed as written]:

“They say we will starve through laziness that is not so. But it is true we will starve at our present wages. They say we will steal we can say for ourselves we had rather work for our living. give us a chance. We are Compeled to work for them at low wages and pay high Rents and make $5 per week and sometimes les. And paying $18 or 20 per month Rent. It is impossible to feed ourselves and family – starvation is Cirten unles a change is brought about.”

Examples like the one I cite above provide more evidence that public policy in the U.S. was developed to create and then enshrine black failure. I don’t know how one can fairly look at history and not come to this conclusion.

A recent comment made on Twitter by the brilliant Dr. Sharpe (who I cited earlier) led to a question that has been rattling around in my brain: “What if most people (including some who are black) in the U.S. actually don’t care about the decimation of black people?” For many, this may in fact be a rhetorical question. But for me, it isn’t. The response that one offers must necessarily shape our interventions, strategies, and ideas about social change and justice.

And so the question that we are left to answer is: “What if no one cares about black survival because we were actually never meant to survive?” Where does this leave those of us who want to see an end to racialized mass incarceration or to the subjugation of black women & girls? Who should we be “convincing” to join in that struggle? How are we supposed to build power within this context?

It’s been a “slow motion genocide” for Black people since our arrival on American soil but we’ve refused to go “gently into that good night.” It’s clear that the cavalry isn’t on its way to save us and so we must do what we’ve always done; we must save ourselves. The question that remains for those of us who do care about black survival and who want to confront black women’s subjugation is “how?”

What I re-learned last night is that some of those who I might have enlisted as allies in the struggle to reverse this “slow motion genocide” are in fact untrustworthy and unreliable. In particular, I want to underscore some comments from those people (mostly men) who took the occasion of real anger and hurt at what the Onion wrote to make obnoxious and unhelpful comments about drones and the security state. Here are a couple of examples but there were many more:

“How do we describe the imbalanced ethical plane where response to a verbal slur is more vehement than response to a series of drone strikes?”

Imagine if we got as much criticism every time we killed a nine year old girl as those comedians are getting for tastelessly insulting one.

The presumption and condescension dripping from these tweets could drown a small child. The underlying assumption is that folks who are outraged about the Onion’s tweet are not also vocally opposed to state-sponsored violence. It’s a snarky way to belittle the justified anger that people were feeling about the Onion’s actions. It also assumes an inability to hold at least two thoughts in one’s mind at once. It is insulting. Speaking for myself, I am a feminist who has worked to end gender-based violence AND I am a prison abolitionist. I am someone who has organized and spoken out against the carceral state and also state-sponsored violence. I am committed to eradicating oppression wherever it exists. All of these things are part of me. All are connected for me. But it was clear last night from some of the tweets that I saw that others are unable to make these connections. I would bet that these same people throw around words like “intersectionality” quite freely. Yet when it comes time to put the words into practice, they fail spectacularly. That’s their problem and not mine. I do know, however, that I want no part of their revolution…