Nobody Matters Less Than Black Girls…

These are some impressions…I am thinking through recent experiences.

The saddest fact I’ve learned is: Nobody matters less to our society than young black women. Nobody. – Jim DeRogatis

This Jim DeRogatis quote has floated across my Twitter timeline several times this week. DeRogatis was referencing the lack of accountability for R.Kelly’s repeated sexual assaults of black girls. I must admit to grinding my teeth every time I’ve seen the quote. It isn’t that I don’t agree with the sentiments expressed by DeRogatis. Rather, I don’t believe that 90% of those who are sharing the quote actually grasp the lived realities of too many young black women and girls in America. So the implications of the quote are too easily ignored. But for hyper-disposable black girls, the pain lingers and festers…

“Nobody matters less to our society than young black women.”

I’ve spent the greater part of my adult life working with black girls and young women. I created a workshop that I co-facilitated several years ago focused on using Lil’ Kim’s image and experiences to illuminate our own lives as black girls and women. In other words, I’ve had a longstanding interest in and commitment to engaging in discussions with black girls about issues of representation and survival.

“Nobody matters less to our society than young black women.”

Since Beyonce released her visual album last week, there have been many, many attempts to analyze, dissect, and discuss it. This is not another post about Beyonce. At least, it’s not a post about whether Beyonce is or is not feminist. It’s also not an album review. It’s a post (I think) about the historical devaluing of black American girls and women and its implications for today.

“Nobody matters less to our society than young black women.”

Early Monday morning, I got a Facebook message from a young woman I mentored years ago. She had a very difficult upbringing and at 15 was struggling a great deal. This is a young woman who did what she had to do to survive. And survive she has. She’s 22 now and reached out to me about a Beyonce-related blog post that an acquaintance had shared on her Facebook page. The acquaintance included the following status update: “That’s right, hoes don’t deserve to live.” I won’t link to the original blog post that the acquaintance was responding to because it is vile, violent, and disgusting. The young woman’s message to me was “Do you think that this blog is saying that hoes don’t deserve to live? I’m confused..” My heart sank because this young woman is still doing what she needs to do to survive and take care of her siblings. I knew what she was asking… And I wanted to cry.

“Nobody matters less to our society than young black women.”

Later on Monday, we spoke on the phone and I found myself struggling to talk about the blog post. [My contempt for the authors of that piece is immeasurable]. We talked about the “fantasyland” (her words) that Beyonce has created through her album. She said that listening to it was like “taking a vacation from life.” I thought that her reaction to the album and her emphasis on fantasy, escape and fun was notable and instructive. Celebration and trauma co-exist. It’s important to remind oneself of this regularly, I think. When I hung up, I was unsatisfied with my responses and restless. I later tried to process with another friend who is a peer but I was still unable to adequately convey my thoughts and feelings.

“Nobody matters less to our society than young black women.”

On Tuesday, I read an essay by Brittany Cooper. While I didn’t relate to everything that she wrote, the following words resonated profoundly: “…we are culturally ill-equipped to deal with black women’s broken, burned and bruised places.” I thought about the whorephobia that my young friend was subjected to on Facebook. She bore the brunt of judgement and violence and was hurt by both. That this vitriol came from another black woman only deepened the wounds.

“Nobody matters less to our society than young black women.”

The present is mostly illegible to me without rooting myself in the past. History is my vernacular; it’s the language that allows me to express my thoughts and feelings about my life and experiences. The past bleeds into the present.

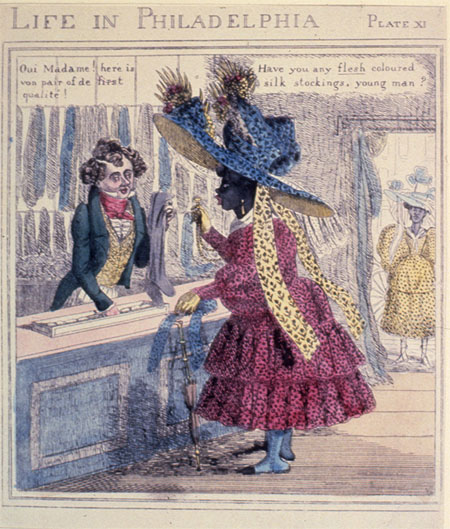

In 1828, a political cartoonist named Edward W. Clay created a series called “Life in Philadelphia.” Through the images that he drew, he sought to demean and denigrate free black people living in Philadelphia, black women in particular. Many of his images featured animalistic caricatures of black women dressed in their ‘finest’ clothes and participating in events that were considered to be the purview of whites. Below is an example of one such cartoon.

Edward Clay – Life in Philadelphia Series (1828) – Source: Library Company of Philadelphia

Caption: “Have you any flesh coloured silk stockings, young man? Oui Madame! here is von pair of de first qualite!”

The purpose of these caricatures was to dehumanize black people (especially black women). If black women were not human, then you were justified in treating them as objects and property. They could be dealt with harshly by the law, punished with impunity, abused at will and worked to death. The cartoons were also a warning to black people that they should know their place and stay in their station; that their ‘freedom’ was an illusion. How dare these ‘uppity’ Negroes compare themselves favorably to white people. These images did the cultural work of disseminating negative messages, reinforcing stereotypes, fanning racial resentment and policing racial boundaries in order to ensure the oppression of blacks.

“Nobody matters less to our society than young black women.”

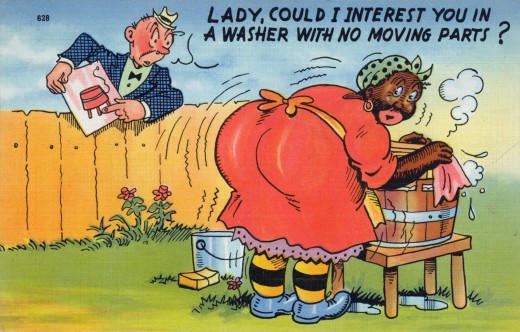

I collect early to mid 20th century postcards. Below is an example of a ‘humorous’ one that reduces a black woman to her body parts.

The white man leering at her is most certainly entitled to avail himself of her as she is mere property. The fence is no barrier. Black women have been and still are always ‘out here’ vulnerable to violence and buffeted by the forces of oppression. Our bodies were held captive, exploited, commodified, and abused. In spite of this, as historians like Stephanie Camp teach us, enslaved people organized “outlaw parties” where they “danced, performed music, drank alcohol, and courted (p.60).” Camp (2004) quotes Nancy Williams who was formerly enslaved recalling how she would get “out dere in de middle o’ de flo’ jes’a-dancin’; me an’ Jennie and de devil. Dancin’ wid a glass of water on my head an’ three boys a bettin’ on me (p.60).” So even under the most heightened policing of their bodies and their mobility, enslaved people sought ways to resist and assert control over their lives. They also looked to embrace some pleasure in the middle of hell. Camp writes:

Despite planters’ tremendous effort, enslaved women and men routinely “slip[ped] away” to attend illicit parties where such sensual pleasures as eating, dancing, drinking, and dressing were among the main amusements. […] Enslaved partygoers had a common commitment to delight in their bodies, to display their physical skill, to master their bodies through competition with others, and to express their creativity (p.61).

And so it appears that for us as black people, trauma and domination have always co-existed with pleasure and celebration. It is with this historical context as backdrop that Beyonce released her “visual album” this past weekend to great fanfare and debate. The past bleeds into the present as sense memory reminds us that we were property and that our bodies were violable hypersexualized flesh. We rage and turn our anger towards our reflections sometimes. We can hardly believe that we are still here when we weren’t actually meant to survive. We have few words to convey our mountains of hurt and of pain. We can’t imagine desire or pleasure without penalty. We’ve survived and my young friend is surviving still. We don’t know how to heal our “broken, burned, and bruised places” yet but we are searching for the right path. We know that we have never been in style and that chattel slavery’s script was written on our bodies. But even then, we sought ways to resist and to seize control. We created dances, embraced fashion, depicted ourselves in photographs, created homemade birth control technologies, had illegal abortions. We did this, we’ve continued to do this understanding full well that: “Nobody matters less to our society than young black women.”