Whenever I talk about my work with others, I make sure to stress that it focuses on developing community-based alternatives to the traditional criminal legal system. I add that we do this using a transformative justice approach and lens. Many have responded to me by saying: “that’s not something that I can wrap my mind around.” This is usually followed by the questions: “What does transformative justice look like?” and “How would it work?” Actually I should back up to say that the first question is usually: “What about the violent and bad people? Surely you are not advocating letting them out of prison!”

I understand the fear that people have of the so-called “unknown.” People would rather rely on a criminal legal system that they KNOW is ineffective and unjust than to move to an approach that they view as “unproven” and perhaps even Utopian. It provides them with a sense of safety, however fragile. Hence, the constant and persistent question: “What about the bad people?”

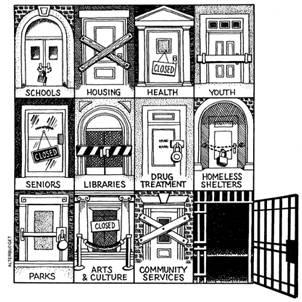

I understand that people want to have some sense of accountability for harm that was done. I often answer questions about the “bad people” by asking individuals whether they feel that every “bad” person is currently incarcerated. If they say, no, I ask them if it is realistic to incapacitate every “bad” person on the planet. In fact, what does it even mean to be a “bad” person? Then I ask them to think about what factors determine who ends up behind bars. This is intended to push people to acknowledge the fact that not every “crime” is punished and that certain groups always seem to be more of a target for punishment than others. I point out that the majority of people who are incarcerated are non-violent offenders. I tell them that if they would agree to release all of those people only then am I willing to entertain their questions about the “bad” people. This serves as a way not to get bogged down in the endless discussion about whether “bad” people need to go to prison. Once all of the non-violent prisoners are freed, I am confident that we would be able to make the case that prisons are in existence to mask our failure for addressing the root causes of oppression. As such, more people would be freed still. We need to start opening the doors of the prisons and this necessitates deploying alternative approaches to addressing violence and crime.

I am prompted to write this post today after reading an article in the Daily Progress about restorative justice. I wanted to write about this topic because it is past time that those of us who are anti-prison activists step up to the plate and create actual community-based alternatives that do not rely on the criminal legal system to solve issues of violence and crime. We cannot simply rely on analysis of the problem of mass incarceration as important as that work is. We have to test our theories about using transformative approaches to addressing violence and crime. We have to be willing to take some risks and to also be prepared to fail some times. More of us have to put our ideas in practice. It takes courage because it is lonely and difficult work but we cannot expect to dismantle the prison industrial complex if we do not develop vehicles for community accountability with respect to violence and crime. We can start small and that is exactly what we are attempting in our organization.

Many people of good will are looking for concrete examples of restorative and transformative practice in action. Restorative justice as an approach to addressing violence and crime is only one step on a continuum of community accountability. That continuum is ultimately pointing our society towards TRANSFORMATIVE justice.

Over the past few years, I have adopted a hobby of collecting stories and vignettes of restorative and transformative justice in action. To date, the best example of what I mean by transformative justice is a story that I heard a couple of years ago on NPR about a man named Julio Diaz. The title of the story was “A Victim Treats His Mugger Right.”

Julio Diaz has a daily routine. Every night, the 31-year-old social worker ends his hour-long subway commute to the Bronx one stop early, just so he can eat at his favorite diner.

But one night last month, as Diaz stepped off the No. 6 train and onto a nearly empty platform, his evening took an unexpected turn.

He was walking toward the stairs when a teenage boy approached and pulled out a knife.

“He wants my money, so I just gave him my wallet and told him, ‘Here you go,'” Diaz says.

As the teen began to walk away, Diaz told him, “Hey, wait a minute. You forgot something. If you’re going to be robbing people for the rest of the night, you might as well take my coat to keep you warm.”

The would-be robber looked at his would-be victim, “like what’s going on here?” Diaz says. “He asked me, ‘Why are you doing this?'”

Diaz replied: “If you’re willing to risk your freedom for a few dollars, then I guess you must really need the money. I mean, all I wanted to do was get dinner and if you really want to join me … hey, you’re more than welcome.

“You know, I just felt maybe he really needs help,” Diaz says.

Diaz says he and the teen went into the diner and sat in a booth.

“The manager comes by, the dishwashers come by, the waiters come by to say hi,” Diaz says. “The kid was like, ‘You know everybody here. Do you own this place?'”

“No, I just eat here a lot,” Diaz says he told the teen. “He says, ‘But you’re even nice to the dishwasher.'”

Diaz replied, “Well, haven’t you been taught you should be nice to everybody?”

“Yea, but I didn’t think people actually behaved that way,” the teen said.

Diaz asked him what he wanted out of life. “He just had almost a sad face,” Diaz says.

The teen couldn’t answer Diaz — or he didn’t want to.

When the bill arrived, Diaz told the teen, “Look, I guess you’re going to have to pay for this bill ’cause you have my money and I can’t pay for this. So if you give me my wallet back, I’ll gladly treat you.”

The teen “didn’t even think about it” and returned the wallet, Diaz says. “I gave him $20 … I figure maybe it’ll help him. I don’t know.”

Diaz says he asked for something in return — the teen’s knife — “and he gave it to me.”

Afterward, when Diaz told his mother what happened, she said, “You’re the type of kid that if someone asked you for the time, you gave them your watch.”

“I figure, you know, if you treat people right, you can only hope that they treat you right. It’s as simple as it gets in this complicated world.”

Produced for Morning Edition by Michael Garofalo.

If you have an interest in issues of transformative justice, you absolutely have to LISTEN to Julio as he narrates his story. The story has all of the elements of transformative justice: healing, compassion, relationship-building and accountability.

For more stories that address themselves to transformative justice, I recommend the work of Creative Intervention’s Storytelling and Organizing Project.

Sometimes my anti-prison work has me looking for outlets where I can just laugh. Well when I came across this quote, I laughed out loud.

Sometimes my anti-prison work has me looking for outlets where I can just laugh. Well when I came across this quote, I laughed out loud.