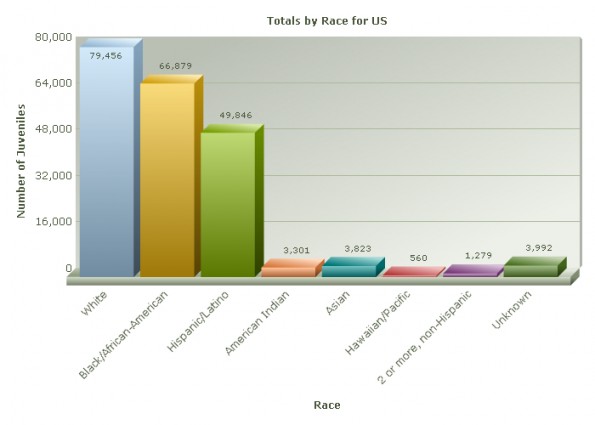

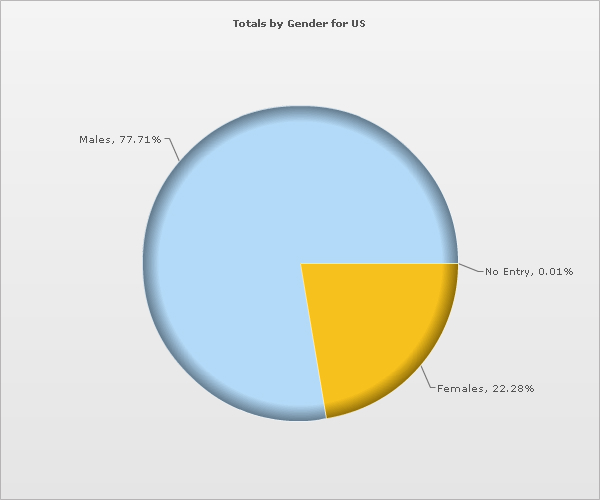

Census of Juveniles on Probation

I’ve been waiting for this information and they are now offering preliminary data from the Census of Juveniles on Probation. This is a snapshot as of yesterday and the numbers should be considered preliminary

For more details, click here.

What exactly is the prison industrial complex?

The Urban Politico just featured an interview with Sarah Catharine Walker of the Second Chance Coalition. The most interesting part of the exchange for me is this one:

When I mention prison industrial complex to most people, they look at me like some weird, conspiracy theorist. What does this term mean to you?

Personally, while I am sympathetic the Prison Industrial Complex concept I have not found it useful in a legislative advocacy. The term industrial complex is over-used and lacks clear definition. When a concept is too inclusive or amorphous it makes it difficult to attack specific issues. When I work with college interns I frequently hear the term Prison Industrial Complex, Non-Profit Industrial Complex, the Social Service Industrial Complex and the Military Industrial Complex. I think the term industrial complex offers too easy an out for advocates. It makes the work seem daunting and impossible. How does one take on the industrial complex. Perhaps more importantly, for me, the concept of the prison industrial complex is really a question of resource allocation. Where do we allocate our resources? In social support programs or in our justice system? We need to shift the conversation to focus on resource allocation that prioritize outcomes that support individuals, their families and the communities where they live. Our policies should support the outcomes we desire: public safety, reduced recidivism, healthy communities and families, and more efficient use of our resources. Our current policies often work against the public interest by creating a system of “perpetual punishment.” In truth, in MN, the coalition has worked to develop and establish partners in public safety. Increasingly with diminishing budgets and increased research on what is actually effective many law enforcement professionals and corrections professional would also like to see reduced barriers.

Over several months this year from January to June, my organization ran a Saturday Communiversity course about the prison industrial complex. It was a free course offered to community members in a community setting. We had excellent attendance and participation throughout. You can find information about that course here. I still have to update that blog with information from our final June session. We’ll get to that this month.

Here is part of what I wrote about why the term PIC resonates with me:

Personally, I continue to find the term “Prison Industrial Complex” to be a good frame for discussing the issues that we have over the past five months. This is why I continue to use it. In particular, I rely on Critical Resistance’s definition:

“Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) is a term we use to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to what are, in actuality, economic, social, and political ‘problems’.”

Teaching about Prisons and Abolition: the Latest Issue of Radical Teacher

The latest issue of Radical Teacher is devoted to teaching about prison abolition and it is excellent. I have been thinking a lot about teaching lately since I have now returned to the classroom this fall after a 5 year hiatus. I had been feeling burnt out with respect to teaching college students. I am stepping back in now feeling much more energized and excited.

In the introduction to Radical Teacher, the editors offer this window about their discussions in putting the issue together:

The conversations we had during meetings of the Editorial Board of Radical Teacher mirrored the debates on the left about how best to resist the PIC. Many members of the Board felt that the contemporary PIC abolition movement was utopian in the pejorative sense — a pie-in-the-sky faction ungrounded in the socio-political possibilities of this historical juncture. Others expressed the commonly held fear that prisons, though overly relied upon in the United States, are necessary institutions to house those members of society who have caused certain kinds of harm, such as murderers, rapists, and perpetrators of hate crimes. While those of us on the left might imagine ourselves to be less inclined to be persuaded by arguments for the necessity of prisons based on the racialized “threat” of the “criminal,” we sometimes have a hard time knowing where else to turn to address violence against queer people, people of color, immigrants, and others.

The honesty in this paragraph is wonderful. It is of course true that even those of us who consider ourselves to be progressive on a number of social issues still find ourselves struggling with internalized oppression. This is an inescapable fact of life. The important thing is to notice this and to struggle to overcome it.

Two friends of mine, Jessi Lee Jackson and Erica Meiners, also have a terrific essay in this issue. They wrote a piece titled “Feeling Like a Failure: Teaching/Learning Abolition through the Good the Bad and the Innocent.” The essay opens with two examples from the authors. I will include Jessi’s example here:

It is the 8th week of English class in our adult high school completion program, and we have just read a short excerpt from Angela Davis’s Are Prisons Obsolete? As a class, we review vocabulary words, and then, piece by piece, work to understand Davis’s argument for prison abolition. All of the students have firsthand experience of the system, and they agree that the prison system is clearly racist in its impact. But when we get to the point of discussing abolition — of shutting down prisons — the class quiets. The disagreements start. “I agree with abolishing the death penalty, but…” “But some people need to get locked up.” “I agree we need to change the system, but getting rid of prisons entirely,,,” “It’s too much…” “I don’t think we need to go that far…”

I find myself in the awkward position of being the only person without direct experience of being locked up, and the only vocal abolitionist. By the end of our conversation, I perceive that students have made up their minds and are united in their analysis: the prison system is messed up, but abolition is “going too far.” I wonder to myself what went wrong in our conversation. Why was I not able to present abolition in a way that challenged people to go further or question their assumptions about the necessity of prisons?

Jessi and Erica are both long-time anti-prison activists and educators. They bravely lay out their challenges in teaching abolition to students with experience in the criminal legal system. The examples that they offer are excellent because so many of us who teach about prisons and abolition have encountered similar resistance.

They offer this important insight in the essay:

We believe it is key to not rest with the what about the bad people questions or to ignore the feelings produced through and by the PIC, but to explore these fears by responding to the “bad” people statements with the question: “What would we do about violence without prisons?” We believe this is an important question, one that needs to be asked in multiple contexts. What are we doing about violence, both interpersonal and state-sanctioned? What are we doing to confront and defuse racist fears? This reframing renders visible how the original question, “what about the bad people?” masks the reality that prison offers a false answer to the question of violence, actually shifts resources and energy from meaningful and sustainable anti-violence work. Abolition frameworks point out that anti-violence work needs to be centered, not around identifying and caging bad people, but in responding to and preventing violence.

I think that this is a key reframing that provides a real opportunity to engage more people in discussions about abolition. Read the entire issue, you won’t be sorry. Over the next few days, I will be highlighting other selections from the issue.

I’m back to teaching today so I will be taking a blogging break…

I don’t know what possessed me to agree to teach a sociology course this semester. I did this several months ago before I knew how much busier I would be than ever… So my course starts this evening and I have to actually work on my lecture… I will be back to blogging tomorrow.

Adventures in Zero Tolerance Land #5: Suspended for “I Heart Boobies”

It seems that zero tolerance policies in American schools will provide me with something to blog about on a daily basis. Now comes the news that a young man has been suspended from school for refusing to give up his “I heart boobies” bracelet.

Here’s the story:

A Rocklin High School sophomore faces disciplinary action for wearing a controversial bracelet that proclaims “I heart boobies,” then refusing to turn it over to school officials.

Hunter Cooper, 15, said he wore the bracelet since the first day of school. His mother gave it to him after she picked it up from a doctor’s office. For five months before that, he had the pink survivor bracelet from Susan G. Komen. Then last Friday, school officials spotted him with the black “boobies” bracelet and asked him to remove it.

“I’m wearing it in honor of my grandmother,” said Cooper, who said his grandmother died before he was born. “I don’t see it as an offensive thing at all.”

The black bracelet with white lettering also trumpets other slogans, such as “wearing breast,” “save the breast” and “keep a breast.”

A Keep-A-Breast.org spokesperson said its breast cancer awareness campaign is targeting teens.

“This is a modern word, I think. I know plenty of people who use the word boobies,” said Cooper.

“We support the cause 100 percent,” said Rocklin principal Mike Garrison. He said several staff members at Rocklin High School have battled breast cancer.

“But, not the language on the bracelet,” said Garrison. “When you use the term boobies, we find, and many people find, the term offensive and inappropriate. We find it inappropriate to be wearing it on school grounds.”

Rocklin High officials asked Cooper to hand over the bracelet, but he refused. Cooper said he now faces Saturday school or one day of on-campus suspension for not complying.

A female student at Rocklin High reportedly attended Saturday school over the weekend and was disciplined after refusing to turn over her “I Heart Boobies” bracelet.

The principal would not discuss Cooper’s case or confirm if Cooper faces disciplinary action. Principal Garrison would not discuss the other student’s case either.

“We have not suspended any student or disciplined any student for wearing a bracelet or shirt that has that insignia on it,” Garrison said.

“I guess I was being too defiant because I didn’t hand it over,” said Cooper. “I don’t really think those are fair punishments.”

Cooper said his grandmother died from breast cancer five months after his grandfather died from lung cancer. Several other family members and friends have battled cancer. Cooper owns various bracelets as a show of support– including the well-known yellow Livestrong bracelet.

Cooper’s mother said she was disappointed with the way the school and the district handled the issue.

“Without having a discussion and handing out penalties first, I think that’s a real problem,” said Danielle Cooper. “They need to inform us as parents. I’d like them to handle the subject matter as mature adults. I’d like the staff to take a stand, one way or another. If they banned (the bracelets), and why they banned them, we should receive notice.”

Garrison said school administrators will be meeting Tuesday for a leadership meeting and will be discussing their position.

By Suzanne Phan, [email protected]

Thoughts?

A Young Woman’s Response to Yesterday’s “Stand By Your Man” in Prison Posting

I received an e-mail from a young woman based on Monday’s blog post about hip hop’s “stand by your man” in prison problem. In that post, I highlighted a number of past videos and songs to buttress my argument about the cultural expectations that are being placed on young women of color to wait out the incarceration of their partners.

I asked the young woman who sent this to me for permission to share a part of her e-mail here and she agreed:

“I wanted to let you know that I live that life that you wrote about. My boyfriend is locked up serving a fifteen year sentence in prison. We have a baby together and I am 21. Everyone expects me to just wait for him to get out. I do love him but I also feel that he made a mistake and now I have to do his time too…I am at community college now and I am trying to make a better life. I just found your website because I was writing a paper about prison life for a sociology class this summer and now I read it all of the time. I just wanted to send you this e-mail because I don’t think that everyone should expect young girls to just have to wait for their men to get out of prison and for us not to live our own life too. It’s hard and not easy.”

The young woman also suggested another video to me that addresses the issue of the young women left behind in this epidemic of incarceration of men of color. She said that it was very popular among her peers. I am including it here. It is by a group called Aventura and the song is called “El Malo.”

Here are the first couple of stanzas of the song translated from Spanish to English:

The Bad One

He gives you his love

You sleep with doubts

Now you see that routine

Is not what it appeared to be

He’s sincere, contrary

To my defects but I’m still

The bad one that you can’t stop lovingYou might be the cinderella

In the fairy tale that gives pity

And even if i’m not a prince charming

I’m your love and your dilemma

And just like in the novels

I’m the bad boy with a virtue