The Gendered Nature of Prisoner Resistance and the Invisibility of Women Prisoners’ Organizing

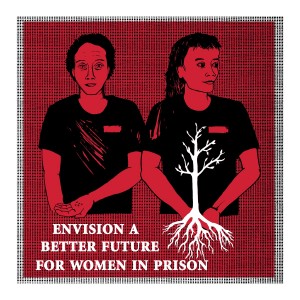

In light of the Georgia prisoner protest and uprising, I thought that this would be a good time to address the gendered nature of prisoner resistance. The most well-known and well-publicized examples of prisoner resistance are decidedly male-centric. Many people, even those who are unfamiliar with prison activism, can name the Attica Rebellion, George Jackson and others. When we think of prisons and prisoners in general in the U.S., we tend to think of men and in particular men of color. Women prisoners are rendered pretty much invisible in the public imagination. And yet, there have been numerous acts of resistance by incarcerated women over the years. The reasons for the invisibility of these acts of resistance are many and I won’t address those today. Instead, I hope to answer the following question: How have women prisoners individually and collectively challenged the conditions of their incarceration?

Victoria Law, in her book Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women, provides the most comprehensive account of the history of women prisoners’ resistance. Law presents the case of Carol Crooks as one such example of resistance:

“In the 1970s, Carol Crooks, a prisoner at the maximum-security Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in New York, initiated a lawsuit against the prison, its warden and several staff members. She claimed that the prison’s practice of placing women in segregation without a hearing and refusal to provide 24-hour notice of charges violated their constitutional rights. On July 2, 1974, a court agreed with Crooks, issuing a preliminary injunction, prohibiting the prison from placing women in segregation without 24-hour notice and a hearing of these charges.

The next month five male guards beat Crooks and placed her in segregation. Her fellow prisoners protested by holding seven staff members hostage for two and a half hours. However the “August Rebellion” is virtually unknown today despite the fact that male state troopers and (male) guards from men’s prisons were called to suppress the uprising, resulting in 25 women being injured and 24 women being transferred to Matteeawan Complex for the Criminally Insane without the required commitment hearings.”

Women prisoners’ resistance often looks different from that of men. However there are and have been countless examples of individual and collective actions by women to challenge the conditions of their incarceration. A powerful way that women prisoners have resisted has been through their writing and creation of media. The following words by Assata Shakur provide a good example of this:

“There are no criminals here at Riker’s Island Correctional Institution for Women (New York), only victims. Most of the women (over 95 percent) are black and Puerto Rican. Many were abused children. Most have been abused by men and all have been abused by “the system.” There are no big time gangsters here, no premeditated mass murderers, no god mothers. There are no big time dope dealers, no kidnappers, no Watergate women.

There are virtually no women here charged with white color crimes like embezzling and fraud. Most of the women have drug related cases. Many are charged as accessories to crimes committed by men. The major crimes that women here are charged with are prostitution, pickpocketing, shop lifting, robbery and drugs. Women who have prostitution cases or who are doing “fine” time make up a substantial part of the short term population. The women see stealing or hustling as necessary for the survival of themselves or their children because jobs are scarce and welfare is impossible to live on.”

This is an excerpt from a longer essay by Assata Shakur published in the Black Scholar in 1978 called Women in Prison: How It Is With Us. Resistance comes in many forms. It is important for us to underscore women prisoners’ resistance too.