Domestic Terrorism Pt.2: Youth Criminalization & Police Power

I have previously addressed the issue of police violence as a form of domestic terrorism. Recently I have been following the case of a young man named Jeremy Marks and I have no idea why this isn’t engendering more of a national outcry.

Jeremy is a black high school student who is accused of attempting to “lynch” a school police officer. You read that correctly; “attempted lynching” is one of the charges against the young man. An article in LA Weekly provides key information about this situation:

On Dec. 2, Jeremy Marks, a Verdugo Hills High School special education student, was offered a new plea offer by the L.A. County District Attorney: If he pled guilty to charges of obstructing an officer, resisting arrest, criminal threats and “attempted lynching,” he’d serve only 32 months in prison.

That actually was an improvement from the previous offer made to the young, black high schooler — seven years in prison.

It is critical to understand how often the state tries to force people to accept plea deals against their best interest. The courts are overrun and prosecutors consistently offer plea deals as a way to expedite cases. However most defendants would actually be better served to take their chances in court given the fact that prosecutors in criminal cases have a high bar for successful convictions. Proving that something happened beyond a reasonable doubt puts the burden on the state to make a credible case.

Here’s more about the Jeremy Marks situation:

Marks, 18, has been sitting in Peter Pitchess Detention Center, a tough adult jail, since May 10. Bail was set at $155,000, which his working-class parents can’t pay to free their son for Christmas. His mother is a part-time clerk at a city swimming pool, his father is a lab tech.

The first thing to understand is that Jeremy Marks touched no one during his “attempted lynching” of LAUSD campus police officer Erin Robles.

The second is that Marks’ weapon was the camera in his cell phone.

The third is that Officer Robles’ own actions helped turn an exceedingly minor wrongdoing — a student smoking at a bus stop — into a state prison case.

The altercation that has ruined Marks’ life occurred in early May at a Metro bus stop on a city street a few blocks from Verdugo Hills High School as about 30 kids were waiting to board a bus.

The reason that I blog so often about the school to prison pipeline and the impact of harsh school disciplinary policies is because of situations like the Marks case. Having police officers in and around the vicinity of schools causes more harm than it does good. Small altercations are transformed into “aggravated” assaults. The presence of police in and around schools is NOT about increasing student “safety” instead it criminalizes many more young people.

Witness accounts say campus police officer Robles challenged an unnamed 15-year-old for allegedly smoking — it’s unclear whether he was smoking or just holding what has been variously reported to be a cigar, cigarette or joint.

When the 15-year-old resisted, Robles grabbed and shoved him, according to eyewitnesses.

In Robles’ sworn statement, she says she pulled the resisting boy to the ground as other students shouted “Fuck you!” and Marks called out the name of the gang Piru Bloods.

Robles testified that the minor who allegedly was smoking “is screaming, ‘Hit me, fucking bitch, hit me, you stupid bitch, hit me, you dyke!'” When that boy turned his body and possibly elbowed her, Robles says, “That is when I did strike him,” with her expanded baton, “about three times in the left leg.”

She further stated that she sprayed him with pepper spray. The kid then hit her hand, she dropped her pepper spray can, and another student grabbed it off the ground.

Students and Berry-Jacobs allege to L.A. Weekly that Robles then slammed the student’s head against the bus window — a violation of numerous police policies. After that, several stunned students got out their cell phone cameras to record what was unfolding.

Robles struck the 15-year-old’s head on the window so hard, eyewitnesses tell the Weekly, that the window was forced out of its rubberized casement and broken.

Robles has changed her story in documents obtained by the Weekly, as she describes which student allegedly called out, “Kick her ass!” — the phrase at the heart of Cooley’s case against Marks, and the basis of the “attempted lynching” charge against him.

This excerpt cited above has all of the elements doesn’t it? It involves a young person (maybe, perhaps, don’t know) smoking marijuana. So the police officer is presumably making the case that she is acting to support our country’s war on drugs. We have a supposedly “resistant” student who is begging to be assaulted. We have Marks who is apparently invoking “gang” affiliations. We have an instance of homophobia as the officer is purportedly called a “dyke.” All of this allegedly prompts the police officer to beat the 15 year old with her baton and pepper spray him. As we know the Southern Poverty Law Center has filed a lawsuit claiming that students in Birmingham are regularly maced and pepper sprayed. So apparently this is not unusual across the country. Awful! Then the cop slams this young person’s head against glass which prompts students to start filming the encounter.

You know that police officers HATE, HATE, HATE to see the cell phone cameras come out of witnesses’ pockets. Recall that police tried to confiscate cell phones and recording devices at the BART station after the killing of Oscar Grant. Additionally, I have previously written about a case where a man was facing 16 years in prison for videotaping a traffic stop.

The L.A. Weekly report goes on to suggest that two student videos of Marks using his cell phone to film the encounter tell a very different story than the one that is being promoted by the cop and the prosecutors.

You can view the student videos here. They show “Marks in a grayish shirt, getting out his cell phone as he stands in the background of the scene near a student in a white shirt.”

Here is the second student video:

From the L.A. Weekly story:

Marks tapes the final minutes of the MTA bus stop altercation as several students — not including Marks — loudly and repeatedly taunt Robles.

The videos appear to show that Robles had little ability or training to handle razzing from angry high schoolers. She holds the 15-year-old against the MTA bus as he repeatedly tries to slap and push her hands off, and she never appears to have him fully under control.

She turns several times to look behind her at rowdy students, several feet away on a low wall, who jump around and cheer for the student Robles is grasping.

The videos show the loudest and angriest student in a black shirt and sweatpants rushing a few feet toward Robles more than once, and another student in a striped shirt moving toward her — but not Jeremy Marks.

In the videos, Marks, in his grayish shirt, can be seen speaking once. He never joins the extended taunting or picks anything up off the ground.

One really has to feel some sympathy for this police officer who was obviously in over her head. She should not have escalated the situation over a smoking incident. Additionally it is clear that she is outnumbered and outmatched by the students who are all around her.

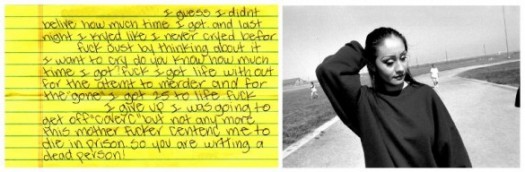

Obviously this whole fiasco has also taken a toll on Jeremy Marks and on his family:

Marks’ mother, Rochelle Pittman, has barely been able to sleep since the campus cops and Los Angeles County prosecutors began to single out her son as the bad actor that day.

Yet he had no physical contact with anyone during the bus incident, was shown on video to be among the quieter students watching the altercation, and spent much of the time taking pictures of it with his cell phone.

The family recently hired two new criminal defense attorneys, Mark Ravis and Karen Travis, to defend him.

It is difficult to relay the emotional, psychological, and financial costs of these types of incidents on the young people who are targeted in this way. To understand the full context of this story, the entire L.A. Weekly article is worth-reading.