‘Free Joan Little’: Reflections on Prisoner Resistance and Movement-Building

Following up on my post about the invisibility of women prisoners' organizing efforts and on the occasion of news that Sara Kruzan has had her sentence commuted, I thought that folks might be interested in revisiting the “Free Joan Little” movement as an example of successful cross-issue organizing that could provide a useful template for the present. First, a short summary of the facts of the Joan (pronounced Jo Anne) Little case.

At 4:00 A.M. on August 27, 1974, officers at the Beaufort County Jail in Washington, North Carolina discovered the body of guard Clarence Alligood in a cell. Nude from the waist down, he had been stabbed 11 times. His trousers were bunched up in his right hand. The fingers of his left hand enclosed an ice pick. The cell’s occupant, Joan Little, age 20, had been serving a seven-year sentence for robbery; now she was gone. One week later she surrendered to authorities. The story she told made headlines. Little, a black woman, claimed that the 62-year-old white jailer had forced her into performing a sexual act, and that she had killed him in self-defense.

Source: Joan Little Trial: 1975 – Sexual Advance Prompts Killing, A Quick Acquittal

Here’s how Time Magazine described the trial in 1975:

In the dark-paneled courtroom in Raleigh, N.C., the 21-year-old black defendant testified in a voice that was so low that jurors often had to cup their ears to catch her words. She clutched a tissue but broke down in tears only once. Otherwise, Joan Little remained remarkably self-possessed through two days of painful testimony and cross-examination, sticking stoutly to her story that she had been defending herself from rape when she stabbed white Jailer Clarence Alligood to death with an ice pick in the Beaufort County Jail in Washington, N.C., on Aug. 27,1974.

Her appearance on the witness stand was the climactic moment in the five-week-old trial, which had become a cause celebre among feminists and civil rights activists (TIME, July 28). Citing mostly circumstantial evidence, Prosecutor William Griffin contended that she lured the 62-year-old jailer into her cell with a promise of sex and then killed him in order to escape from the jail, where she had spent 81 days after being convicted of breaking and entering.

Eventually, Joan Little was acquitted by a jury after 78 minutes of deliberation and returned to jail to serve time for her original offense which was a break-in. Ms. Little escaped in October 1977, a month short of possible parole.

She was recaptured in Brooklyn that December after a high-speed car chase. North Carolina’s request for extradition touched off wide protests among civil-rights advocates and others who said it would be tantamount to a death sentence.

After long court battles, Ms. Little was sent back to Raleigh to serve out her sentence plus time for escaping. She was freed in June 1979 and returned to New York. Source: New York Times

These are the broad contours of Joan Little’s 1974 case.

What I want to talk about today is the movement that was mobilized to free Ms. Little from prison. Jerry Paul was the lead attorney on Joan Little’s case. He and some early supporters of Little traveled the country telling her story at rallies, in the media, etc…. Even People Magazine published a story about the case. They used an organizing strategy that involved seeking the support of feminist organizations, anti-rape organizations, civil rights groups, black power activists, and the like. In an earlier post, I shared that Rosa Parks was a founder of the Joan Little Defense Committee in Detroit.

Paul was joined by Karen Galloway, the first African-American woman to graduate from Duke Law School, who signed up to join the legal team on the same day that she passed her bar exam (McGuire 2010, 214).

In 1975, Angela Davis wrote an essay in Ms. Magazine that brought national attention and even more supporters to Joan Little’s cause. In her book At the Dark End of the Street, historian Danielle McGuire provides a sample list of some of the organizations, groups, and individuals who organized to support Joan Little’s cause. These included: the Southern Poverty Law Center (with Julian Bond at the helm), the Women’s Legal Defense Fund, the Feminist Alliance Against Rape, the Rape Crisis Center, the National Black Feminist Organization, the National Organization for Women, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, some local chapters of the NAACP (though not the national group), and Maulana Karenga, just to name a few.

Bernice Johnson Reagon, civil rights activist and founder of Sweet Honey in the Rock, penned a song called “Joanne Little” which became an anthem for the “Free Joan Little” movement. Here are the lyrics of that song:

Joanne Little, she’s my sister

Joanne Little, she’s our mama

Joanne Little, she’s your lover

Joanne the woman who’s gonna carry your child.Verse 1

I’ve always been told since the day I was born

Leave those no good women alone

Child you better keep your nose clean

keep your butt off the street

You gonna be judged by the company you keep

Said I always walked by the golden rule

Steered clear of controversy I stayed real cool

Till along come this woman little over five feet tall

Charged and jailed with breaking the law

And the next thing I heard as it came over

the news

First degree murder she was on the looseVerse 2

Now I ain’t talking bout the roaring west

This is 1975 at its most oppressive best

North Carolina state the pride of this land

Made her an outlaw hunted on everyhand

Tell me what she did to deserve this name

Killed a man who thought she was fair game

When I heard the news I screamed inside

Lost all my cool my anger I could not hide

Cause now Joanne is you and Joanne is me

Our prison is the whole society

Cause we live in a land that’ll bring all pressure

to bear on the head of a woman whose

position we shareTell me who is this Girl –

and who is she to you?

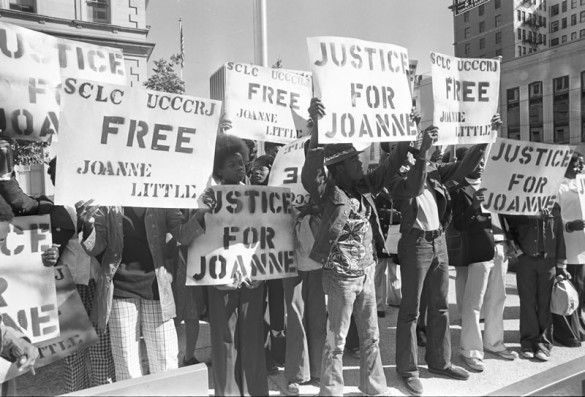

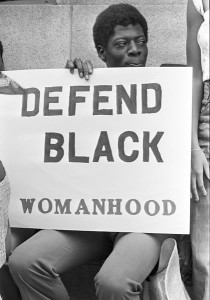

When Little’s trial began on July 15th 1975, 500 supporters rallied outside the Wake County Courthouse. According to McGuire (2010):

“They hoisted placards demanding the court “Free Joan Little” and “Defend Black Womanhood,” and loud chants could be heard over the din of traffic and conversation. “One, two, three. Joan must be set free! the crowd sang. “Four, five, six. Power to the ice pick!”

The Joan Little case affirmed a woman’s right to self-defense. But to me one of the most important aspects of the “Free Joan Little” movement was that supporters insisted that incarcerated women had a right to their own bodies. It was not socially acceptable to rape women in custody. Obviously, we are still a long way from preventing sexual assault in prisons even today but the Joan Little story played an important role in the continuing struggle for social justice.

One has to wonder what it would take to build a similar coalition of groups and individuals in 2011 to take aim at dismantling the unjust prison industrial complex. The “Free Joan Little” movement is instructive because it underscores that it is possible to come together to address prisoner injustice and to WIN.