The Scottsboro Boys, Roy Wright & Juvenile Life Without Parole

The United States is the only country in the world to sentence youth to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Last year, the supreme court ruled that life without parole is unconstitutional for juveniles who have not committed murder. So a youth who was previously sentenced to life without parole for any crime other than homicide can appeal his/her sentence.

In Illinois for example, there are currently 103 people who are serving juvenile life without parole sentences. My fascination with history led me to ask whether there were some prominent cases of juvenile life without parole sentences in the American past.

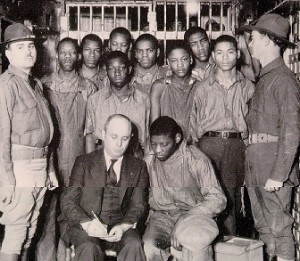

On March 25 1931, police arrested nine young black men at a railroad stop in Paint Rock Alabama after hearing of a fight between black and white youth on a freight train. In the process. they came upon two white women, Ruby Barnes and Victoria Price, who accused the nine young men of raping them. The young men were tried and all were found guilty despite medical evidence that clearly exonerated the boys. The jury could not decide whether to sentence the youngest defendant Roy Wright, who was 13 years old, to life in prison or to death. 11 jurors voted for death while one voted for life in prison without the possibility of parole. The jury was hung. Judge Allfred E. Hawkins immediately sentenced eight of the boys to death by the electric chair. Roy Wright was effectively sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole because he was jailed without a new trial. In 1933, Roy Wright gave an interview to the New York Times.

The firstest I knowed anything was wrong, or knowed who else was on that train was when that crowd of white men stopped the train and Paint Rock and took us off. They took us up the railroad bank to a white rock and stood us against it with their guns aimed at our heads.

One of the white men said to me, “Come on now, nigger, tell us who pushed those white boys off the train, ’cause we don’t want to punish anybody but the guilty ones. If you tell us which ones did it we’ll let you others go.” And I told them I didn’t know anything about it and hadn’t seen nothing.

Then one of them said to me, “You know, nigger, we don’t let no darkies hang around here, and if we catch you anywhere near here after dark we’ll shoot you. Now get going.”

Andy (that’s my brother), Haywood, Eugene and me — we started away. Nobody said nothing until we had walked some little way and then they called us back and loaded us on a truck, tied our hands and feet with rope and carried us to the jail in Scottsboro…

[At the first trials in Scottsboro] I was sitting in a chair in front of the judge and one of those girls was testifying. One of the deputy sheriffs leaned over to me and asked me if I was going to turn State’s evidence, and I said no, because I didn’t know anything about this case.

Then the trial stopped awhile and the deputy sheriff beckoned to me to come out into another room — the room back of the place the judge was sitting — and I went. They whipped me and it seemed like they was going to kill me. All the time they kept saying, “Now will you tell?” and finally it seemed like I couldn’t stand no more and I said yes.

Then I went back into the courtroom and they put me up on the chair in front of the judge and began asking a lot of questions, and I said I had seen Charlie Weems and Clarence Norris in the gondola car with the white girls.

[Later, he said that that testimony was false:]

I didn’t see no white girls and no white boys either.

The Scottsboro Boys case became a cause celebre across the U.S. as an example of the South’s racism and the corruption of the criminal legal system. It was also the most visible and successful example of multi-racial organizing in the 20th century before the black freedom movement of the 50s and 60s.

The Scottsboro Boys case remained consistently in the headlines into the late 1930s. Five of the nine boys would be in Kilby Prison off and on for the next 10 years. Although there were years of appeals, reimprisonment, pardon, compromise, and frustrating negotiation, the case dropped from the headlines after 1939.

The Communist Party engaged in a number of public demonstrations around the country to free the Scottsboro boys. They wanted to use this case to expose the injustices of the criminal legal system in the South. The NAACP worried that the Community Party was using the case for propagandizing and thought that this would not redound to the benefit of the young men.

After 6 years in prison, in 1937, Roy Wright who had been sentenced to life without the possibility of parole was released along with three other Scottsboro defendants. No restitution was made by the State of Alabama.

Roy Wright, the youngest of the boys, emerged from prison at age 19 penniless and untrained for any particular professions. However, the Scottsboro Defense Committee, an organization which had been created to provide legal support to the boys, was able to add a small monthly supplement to whatever the boys could earn on their own.

An article in the Daily Worker by Ben Davis offered the following information about the release of Roy Wright and some of his co-defendants:

“Herself a domestic worker and unemployed for more than a year, Mrs. Wright explained that Roy, even while in jail, would “deny himself things” to send a dollar home. Although Andy (Roy’s older brother who was sentenced to death) is the “sweetest” she went on, Roy has a sense of responsibility “way beyond his age, just like an old man.”

“When I first heard the news I felt like crying, thinking how long my boy had been in jail, his eye-sight nearly failing him from the way the jailers treated him. Even now I tremble when I think how close he came to death. They nearly lynched all the boys in 1931 when they first arrested them. Even after that they kept on sentencing them to die,” Mrs. Montgomery said.

“I didn’t want to cry when I got the news about the boys being free, because I knew everyone else would cry. But that night, I couldn’t help it — I cried all night. This is a real victory for Negroes, especially in the South.”

It is said that Roy Wright was the most successful of the four released in 1937 at reintegrating himself into society. He found a job and married soon after his release. However, twenty-two years after his release in 1959, he found his wife with another man and, in a fit of jealous rage, stabbed her to death. Riven with grief, he committed suicide later that same day. Ultimately Roy Wright did not escape the violence that had been visited upon him by his false imprisonment. Today I am thinking about all of the Roy Wrights that have existed in our history and the current Roy Wrights locked up all across the U.S.

Someone has posted the entire excellent PBS documentary about the Scottsboro Boys case on YOUTUBE. It is well worth watching the whole thing: