Punishing Children: Houses of Refuge & Juvenile Justice

This past Saturday marked the launch of a 30-hour juvenile justice advocacy training program (JJATP) that my organization is sponsoring in partnership with the Jane Addams Hull House Museum. Twenty people came together to discuss the history and to better understand the current manifestations of juvenile justice in Illinois. Our goal with the JJATP is to increase community members’ knowledge about the key issues facing youth in conflict with the law. Ultimately we expect that this increased knowledge and awareness will serve as a catalyst for social change.

It is worth taking a few minutes to think about the current challenges that we face with respect to juvenile justice. Just a couple of days ago, I read a profoundly troubling account of how guards at the juvenile wing of Rikers jail in N.Y. are allegedly encouraging violence among the inmates. It seems important at these moments to recall the roots of juvenile justice (in this instance particularly those in New York).

It is impossible to understand the State’s regulation of children and youth in the U.S. without considering immigration and population growth in the early 19th century. From the mid-18th to the mid-19th centuries, the overall population of the U.S. exploded from 1.5 million to 23 million.

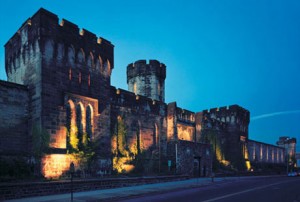

Nowhere were the newcomers to the colonies more visible than in states like New York, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. These mostly Irish and German immigrants were poor and their children moved to cities like New York seeking work. Many of these young people’s parents were seen as unfit because their children were unsupervised and some were committing petty crimes to ensure their own and their families’ survival.

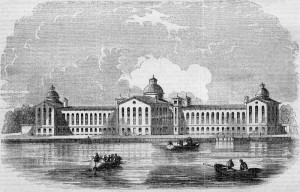

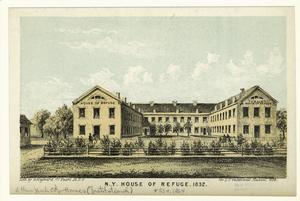

In this backdrop emerged several philanthropic organizations on the east coast dedicated to addressing the problem of “juvenile delinquency.” One of the most prominent of these groups was the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents (SRJD), founded in the 1820s. This group of wealthy businessmen and professionals lobbied the New York State Legislature to pass a bill in 1824 to establish the New York House of Refuge, which was the first correctional institution for youth in the U.S.

Here is how the SRJD described the goals of the house of refuge and defined what it meant by “delinquents”:

“The design of the proposed institution is, to furnish, in the first place, an asylum, in which boys under a certain age, who become subject to the notice of our police, either as vagrants, or homeless, or charged with petty crimes, may be received, judiciously classed according to their degree of depravity or innocence, put to work at such employments as will tend to encourage industry and ingenuity, taught reading, writing, and arithmetic, and most carefully instructed in the nature of their moral and religious obligations while at the same time, they are subjected to a course of treatment, that will afford a prompt and energetic corrective of their vicious propensities, and hold out every possible inducement to reformation and good conduct.”

The following is a description of the early days of the New York House of Refuge:

The reformatory opened January 1, 1825, with six boys and three girls. Within a decade 1,678 inmates were admitted. Two features distinguished the New York institution from its British antecedents. First, children were committed for vagrancy in addition to petty crimes. Second, children were sentenced or committed indefinitely; the House of Refuge exercised authority over inmates throughout their minority years. During the nineteenth century most inmates were committed for vagrancy or petty theft. Originally, the institution accepted inmates from across the state, but after the establishment of the Western House of Refuge in 1849, inmates came only from the first, second and third judicial districts (Ch. 24, Laws of 1850).

A large part of an inmate’s daily schedule was devoted to supervised labor, which was regarded as beneficial to education and discipline. Inmate labor also supported operating expenses for the reformatory. Typically, male inmates produced brushes, cane chairs, brass nails, and shoes. The female inmates made uniforms, worked in the laundry, and performed other domestic work. A badge system was used to segregate inmates according to their behavior. Students were instructed in basic literacy skills. There was also great emphasis on evangelical religious instruction, although non-Protestant clergy were excluded. The reformatory had the authority to bind out inmates through indenture agreements by which employers agreed to supervise them during their employment. Although initially several inmates were sent to sea, most male and female inmates were sent to work as farm and domestic laborers, respectively.

The young people who most often found themselves targeted by early juvenile justice statutes were Irish immigrants. Between 1825 and 1855, 63% of the youth committed to the House of Refuge were of Irish descent. Refuge youth were subjected to corporal punishment including hanging children from their thumbs and severe beatings.

Other states began to open their own Houses of Refuge for youth in the mid-19th century. However over time, these institutions began to suffer from overcrowding and the conditions of the spaces deteriorated quickly. Common practices in many houses of refuge included solitary confinement, the use of the “ducking stool” for girls, handcuffs, and the “silent system.”

Reformers such as those from Hull House began to vociferously criticize the conditions of various Houses of Refuge across the U.S. and a series of court challenges emerged to the refuge movement. The early history of juvenile justice in the U.S. is characterized by intentions falling far short of actions. The notion of humane treatment for “wayward” children gave way to harsh punishment, exploitation, overcrowding, and various other abuses. By the time of the settlement house movement in Illinois and New York, reformers (mostly women) were pushing for changes in the juvenile justice system. One of the greatest advances would be the establishment of the first juvenile court in the U.S. in Chicago in 1899. I will address the establishment of this court next week. In the meantime, I want to end with the words of Judge Julian Mack today.

Judge Mack, who sat on the Juvenile Court bench from 1905-1907, was one of the early reformers who indicted society for creating and then ignoring conditions that produced youth crime. He argued:

The fundamental duty of society is to prevent that child from going wrong: the fundamental duty of society is to recognize the causes that lead to the wrongdoing. The fundamental duty of society is to see what the economic basis is that brings the child into the court and correct that economic wrong. Tear down your hovels and your slums. Give your working man the leisure by enforced limitation of hours of work to give thought to the raising of his own family before you step in and say that he is not competent to deal with his own children.

One can scarcely imagine such a trenchant critique coming from a contemporary juvenile court judge but it would serve all of us well if they would just look back at their own history to reclaim that legacy of social criticism and activism.

Note: For some historical images of the New York House of Refuge, click here.