I am supposed to be on vacation this week and yet I find myself unable to “vacate.” I had made a deal with myself that I would not read anything related to prisons or my work yesterday. I failed on both counts. Anyway, one of the articles that I read described a presentation that Michelle Alexander made to a crowd in Pasedena, California. Here’s the part of the article that jumped out at me:

“Organized by the Pasadena Public Library and the Flintridge Center, with a dozen or more cosponsors, including the ACLU Pasadena/Foothills Chapter and Neighborhood Church, and the LA Progressive as the sole media sponsor, the event drew a crowd of the converted, frankly — more than two-thirds from Pasadena’s well-established black community and others drawn from activists circles. Although Alexander is a polished speaker on a deeply researched topic, little she said stunned the crowd, which, after all, was the choir.”

I want to complicate the concept of “the choir” today. I actually don’t think that in our complicated world there is “a” choir anymore. Rather I think that there are multiple interlocking choirs. In addition, I want to offer a full-throated defense of “preaching to our choirs.”

Years ago, I used to facilitate anti-racism workshops. I must have led at least 30 of them before I recognized that perhaps the person who was best suited to facilitate them was a white person (preferably a white male). I wrestled with myself about the issue because after all I have been the target of racism for my entire life. Who better to “educate” others about racism than me? But as I stood in front of rooms of mostly white people, it became clear that my voice was not the one that had the most impact in changing their ideas about racism in America. Whenever I would co-facilitate these workshops with a white person, I noticed that the message resonated differently. Somehow the audience seemed more willing to listen to the white facilitator’s voice than mine. There are complicated reasons underlying this fact but the reality could not be denied:”White people ‘heard’ other white people about racism differently than they did a black woman.” Even though many of the white people who attended my anti-racism trainings could have technically been considered part of my ‘choir’, they needed a conductor who looked like them in order for their music to really soar.

I retired from running anti-racism workshops in 1999. I have since found that my energy can be put to better use in supporting my anti-racist white friends who are working to educate their own communities about these issues. I have provided resources, training materials, and an ear for them over the years. And frankly, I have found that my blood pressure and level of stress have decreased significantly as a result. I must admit that it was hard to move away from this work mainly because I felt strongly that people of color’s voices should be centered in discussions about racism in America. However, coming to the conclusion that it was white people’s responsibility to take the lead in educating other white folks about racism turned out to be a blessing and frankly a bit of a relief.

“So what role should people of color play in facilitating anti-racism workshops?” you might ask. My answer is simple. Any role that feels comfortable for the individual person of color. There are of course many, many people of color who have and continue to facilitate anti-racism workshops. I don’t want anyone to misinterpret my words. I think that their voices are important and I know that they can and do have a positive impact in addressing racism. For me, I felt that my voice was not as impactful for white audiences as that of my white co-facilitators when discussing racism. I am merely sharing my own conclusions about this work, based on my own personal experiences. My views are not intended to be generalized. Additionally, I have to say that for me those workshops always took an emotional toll. I could not sustain that in any ongoing way. Some people will feel that this was a cop-out but I have made my peace with it. I could not successfully “distance” myself from the issue of racism and therefore I had no business facilitating conversations about it with anyone. Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that the onus for dismantling white supremacy was on white people. I could be an ally but I didn’t want to be at the forefront of that movement.

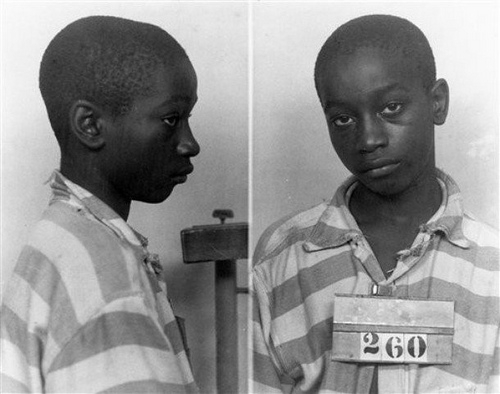

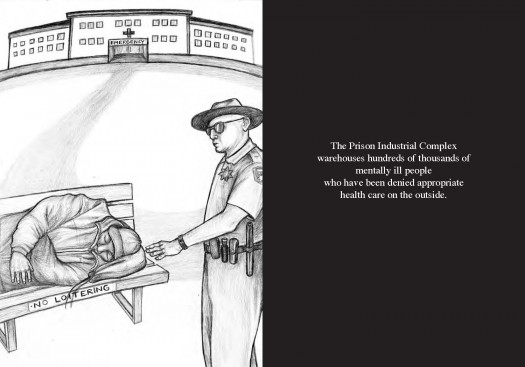

In terms of anti-prison education and organizing, I confront many of the same questions that dogged me when I was doing anti-racism work. [an aside: anti-prison work really is also anti-racism work] This time, however, I find myself in the position of someone who has never been incarcerated. If I am consistent in my thinking, the simple question then is: “Is it the responsibility of those of us who haven’t been incarcerated, to educate our peers about prisons?” If the answer to that question is yes, what role(s) do and should formerly and currently incarcerated individuals play in this work?

In much the same way that I believe that people of color’s voices deserve to be centered in discussions about racism, I think that prisoners’ voices deserve to be at the core of our discussions about the PIC. And yet, I have to ask myself some hard questions about whether their voices carry the same purchase as Michelle Alexander’s with the general public? To certain audiences, it is precisely because Alexander has not been a prisoner that she can be heard and that her arguments can gain purchase.

Let me add another twist to the mix. As a woman of color, I know that some people (mainly white people) will dismiss what I have to say about prisons. “Of course, she is passionate about these issues,” they might say, “After all, black people are particularly targeted and impacted by the PIC.” So once again the issue of race comes up. It always does.When Buzz Alexander speaks about prisons, I believe that he is heard differently on the topic than Michelle Alexander is. As an older white man, his voice carries special authority with certain audiences by virtue of his social location. I may want to rail against this as unfair and perhaps even close my eyes to it but it is simply true. Does this mean that I am advocating that Michelle no longer write and speak about prisons or for that matter that I stop too? Of course not, I just have to recognize that if I want a mass movement to emerge to dismantle the PIC, I have to be willing to concede that I may not be the best interlocutor for certain audiences.

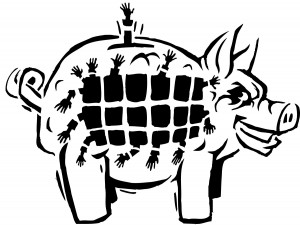

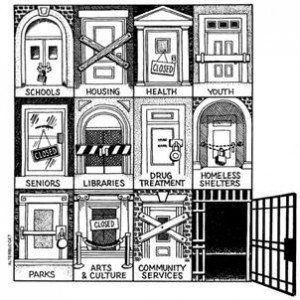

The truth is also that we all have a responsibility to preach to our own choirs. This is not a bad thing. This is not problematic in my opinion. White people need to step up to talk to their communities about mass incarceration. As a black woman, I too need to preach to my choirs (which can include other black women, or former educators, or organizers….). Those of us who are privileged through having escaped mass incarceration have to preach to our choirs of the never-imprisoned. That is our responsibility. It would be wrong for us to sit on our hands and wait for prisoners to take the lead. But this leaves an important question that deserves consideration: How do we avoid speaking for prisoners without the benefit of their involvement in our conversations?

In much the same way that some people of color will resent my call for white people to take the lead in educating their peers about racism, some prisoners will resent my call for those of us who are not imprisoned to take the lead in educating our peers about incarceration. “What do you know about prison?” they will rightly ask. Just as many people of color will ask “What do white people know about the pain of racism?” My answer to both of those questions is that experience gives us special purchase on understanding but privilege also affords its own experience. So long as the voices of the marginalized are taken seriously, centered (to the extent that they can be), and respected then I see no problem. We can do this in different ways but we need to do it.

Did I mention how complicated all of this is? Here’s my main point: I think that we all need to preach to our own choirs. If each of us did this, then true movement-building would be possible. There would be no need to listen to the constant admonitions that those of us who are working in particular communities need to take our messages out beyond our borders. I want to be an ally to other communities but I don’t want to organize them. I want to preach to my own choir(s).