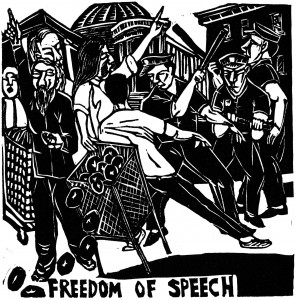

Street Law 101: I Will Not Talk, I Want My Lawyer…

These eight words are the most important ones that you will utter if you are stopped by the police. If you work with young people, you need to drill these words into their heads.

“I will not talk, I want my lawyer.”

I read an article last week about some groups in Pennsylvania who partnered to offer a forum for young black men about what to do if they are stopped by the police. They offered these “10 Rules for Survival When Stopped by the Police:”

1. Be polite and respectful. It is important to make police feel that they are not in a threatening environment.

2. Stay calm and remain in control. You may be scared, but it is important for you to relax. Watch your words, body language and emotions.

3. Do not, under any circumstances, get into an argument with the police.

4. Always remember that anything you say or do can be used against you in a court of law.

5. Keep your hands in plain sight and make sure the police can see your hands at all times. This means you keep your hands out of your pockets and avoid any hand motions or gestures that may be viewed as aggressive.

6. Avoid physical contact with the police. Do not brush against the police in any manner.

7. Do not run from the police even if you are afraid.

8. Even if you believe that you are innocent, do not resist arrest.

9. Do not make any statements about the incident until you are able to meet with your parents, guardian, a lawyer or a public defender.

10. Remember that your goal is to get home safely. Use the above rules to help you navigate a police stop. If you feel that your rights have been violated, you and your parents have the right to file a formal complaint with your local police jurisdiction.

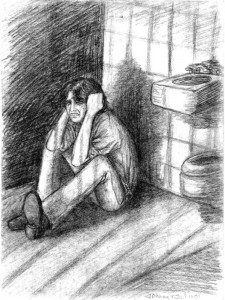

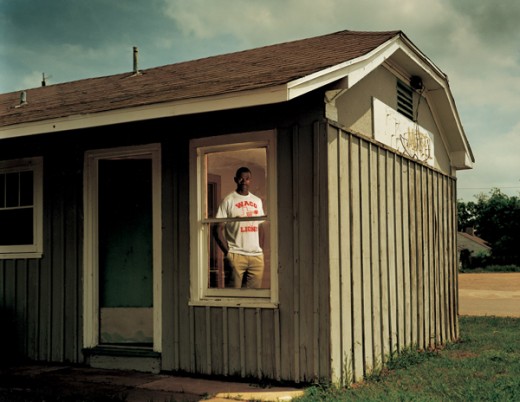

These tips may save a life but they are not a guarantee. Many will find it extraordinarily sad that such a forum even needs to be organized. However the reality is that youth of color, particularly African American young men, are the disproportionately targets of the police. I briefly raised this issue again last week in my post about “dorm room drug dealers.” The reality is that these young people need to be trained in how to interact with the police since they are most likely to come into contact with law enforcement.

My friend Cait has put together this incredibly helpful and valuable two page street law handout for those who live in Chicago in English and Spanish.

“I will not talk, I want my lawyer.” Spread the word…