REPOSTED WITH PERMISSION

I am blessed to meet some amazing people because of the work that I do. I am lucky to know Bob Koehler who is a great writer but most importantly a really good soul. Bob writes a weekly column that I highly recommend to everyone. His column this week really moved me and I asked him if I could share it here. He agreed.

THE HEALING WALLS

By Robert C. Koehler

“There’s something about creating beauty that reaches people and that in the end gives us hope that things can change. . . . It shifts the consciousness of a neighborhood.”

Sometimes people really mean what they say.

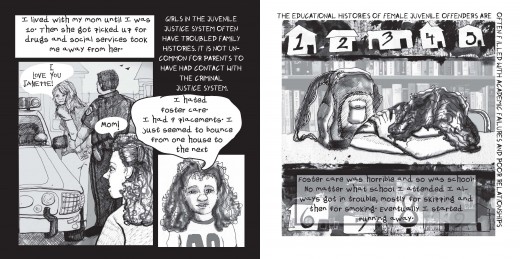

An extraordinary documentary, “Concrete, Steel and Paint,” takes us on a journey of transformation — and it goes the long way, the honest way, through the shoals of anger and mistrust that separate social opposites. The film is about prisoners in a maximum security facility outside Philadelphia. It’s also about crime victims, women and men damaged — driven, in some cases, to the edge of “why go on living?” — by the murder of a loved one, by sexual assault, by some deep violation.

The two groups, so distant from one another — separated, indeed, by the razor wire that winds around the heart — yet so inextricably connected, come together under the auspices of Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program, design and create two linked murals together, and “shift the consciousness of a neighborhood.”

The speaker quoted above is Jane Golden, director of the Mural Arts Program, an internationally acclaimed organization (and a city agency) that has helped residents create more than 3,000 murals throughout Philadelphia over the years. Part of its mission statement is what it calls its Golden Rule: “When we create art with each other and for each other, the force of life can triumph.”

The documentary by Cindy Burstein and Tony Heriza, released by New Day Films, was one of the selections at this year’s Peace on Earth Film Festival in Chicago, and when I saw it I knew I had to write about it. I’ve never seen a more compelling portrayal of the restorative justice, or peace circle, process in action, as the two groups met repeatedly — sat in a circle with one another at Graterford State Prison — and talked about their hopes for the project and the feelings it generated in them.

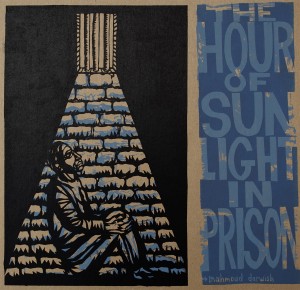

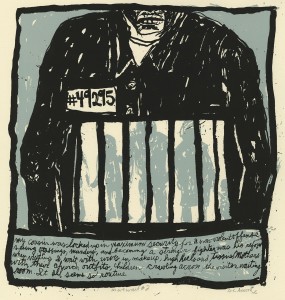

The prisoners, for their part — caught in the consequences of their actions, some of them in prison for homicide — wanted desperately to reach beyond themselves and the severely limited, cut-off lives they were leading. Golden had been invited to speak about her mural work to the prison’s art class. After this initial session, many of the inmates wrote to her, asking for her help in creating a mural that could be given to the city. They wanted to make a contribution.

“I don’t want my legacy to be that I was just a murderer,” said one of the inmates, Zafir. “I do have something to contribute. I’m still a human being.”

Golden knew that this couldn’t be a one-way process, that people on the outside had to be involved as well, and made contact with a victim-advocacy organization in the city. When she presented the inmates’ idea and asked for their participation — all of this is part of the documentary, which unfolds in real time — the reaction among victims was fiercely mixed. Their wounds were raw, their anger was visceral. Their questions were elemental:

“When you realize that an actual person did this — this wasn’t cancer or a sickness,” said the mother of a boy who was murdered. “This was an actual person who shot holes in your child’s body. How can a human being kill another human being?”

But what “Concrete, Steel and Paint” demonstrates is that the human urge to connect is stronger than anger, stronger than hatred, stronger than fear. The two groups met at the prison. The inmates expressed their remorse and talked about their own victimization; the victims and victim advocates were skeptical and challenged this remorse.

The process wasn’t a smooth or simple one. It took over a year of back-and-forth dialogue, along with numerous separate meetings. Eventually the prisoner-artists, working with the Mural Arts Program, came up with a design for a wall. Golden presented it to the victims, who felt anger and dismay. This wasn’t their story. This was the inmates’ story.

At one point, Golden said she wasn’t sure the project was going to come off. Maybe, she lamented, “the naysayers were right. Where is this really going, other than the fact that we seem to have opened up wounds? We’ve waded into really complicated territory.”

What they decided to do was create two walls, which eventually came to be called “The Healing Walls.” One was designed by inmates, one by victims. Both designs are stunning collages of suffering, healing, children, mothers, prison bars, angels and much else. The two groups, working together, painted the designs on panels made of a material called parachute cloth, a non-woven acrylic fabric, which were eventually transferred to bare walls on separate buildings in a rundown Philly neighborhood about half a block apart (3049 and 3065 Germantown Avenue). If you stand in the right place, you can see both walls at once.

As a society, we are stagnant in so many ways, and in no realm is the stagnancy more acute than that of crime, punishment and victimhood. We’re locked in a cycle of violence, cynicism and spiritual anguish that perpetuates itself endlessly — but “Concrete, Steel and Paint” informs us with piercing eloquence that, through art and honesty, salvation and transcendent understanding are possible.

“These two groups that started out so far apart were able to connect,” Golden said. “Even if you connect for just a moment, that moment is reflected in that wall forever.”

Robert Koehler is an award-winning, Chicago-based journalist, contributor to One World, Many Peaces and nationally syndicated writer. His new book, Courage Grows Strong at the Wound (Xenos Press) is now available. Contact him at [email protected] or visit his website at commonwonders.com.

© 2011 TRIBUNE MEDIA SERVICES, INC.