“Bad” Girls: Demonizing Girls in Conflict with the Law

I read an article yesterday that crystallizes some of the conventional thinking about girls in conflict with the law. The Superintendent of Jersey schools was speaking with a group of pastors and had this to say:

“Young ladies” are the community’s “worst enemy,” Superintendent Charles T. Epps Jr. said today to a group of Jersey City pastors.

Discussing the $1 million that Jersey City public schools pay to staff police officers at its facilities, Epps blasted the district’s “young girls.”

“Our worst enemy is the young ladies,” Epps said. “The young girls are bad. I don’t know what they’re drinking today, but they’re bad.”

Concern about girls’ aggression and violence has rarely been higher; largely because the general public feels that girls’ violence is increasing at a remarkable rate. The media has played a central role in this perception, not only in showcasing girls’ violence, but also by providing the public with explanations for this perplexing “new” phenomenon. Headlines have referenced hazing incidents, stories of vicious fights among girl gangs, and an overall explosion of the rates of arrests for aggressive acts.

The past 15 years have seen an explosion in the popular media of books about girls’ aggression and violence. In the 1990s, several popular trade books (Odd Girl Out and Queen Bees and Wannabees among them) announced the emergence of a new prototype of young woman – the “mean girl.” At the turn of the century, media accounts began to concentrate more specifically on the increase of young women’s use of violence. The “mean girl” image would soon be supplanted by the notion of the “violent girl.”

Researchers point to the fact that the image of the “mean girl” is just the latest incarnation of a time-honored stereotype that goes back to the 1960s. First there were the young women revolutionaries like Patty Hearst and Angela Davis, then there were the “gang girls” of the 1980’s, this moved to the “tough girls” of the 90’s, then morphed into the “mean” girl of the early 2000s, finally culminating in today’s “violent bad” girls.

Over the past years, researchers have struggled to catch up with the reality of these popular constructions of girls and young women. Their findings have presented a complicated picture about girls’ aggression and violence. On the one hand, they note an increase in the number of girls who have entered into the juvenile justice system. On the other, they disagree about what this means as to whether girls’ are indeed becoming more violent. In fact, several researchers suggest that a changing culture is more to blame for this rise in the number of girls referred to the criminal legal system than is an actual increase in girls’ use of violence (Chesney-Lind and Irwin, 2007).

In the introduction to their edited anthology “Girls’ Violence: Myths and Realities,” Christine Adler and Anne Worrall (2004) acknowledge that some statistics do suggest “an increase in violent offending by young women in particular (p.5).” While some of these statistics have been used by the media and popular authors to support the view that young women are indeed becoming more violent, Adler and Worrall (2004) caution that “such statistics are as much an indication of definitions of particular behaviors, and criminal or juvenile justice system responses to them and to particular individuals, as they are about the actions of young women (p.5).”

The notion of whether girls’ violence has really increased over time is contested (Adler and Worrall, 2004). Some researchers suggest that the rates of arrests and the reclassification of violent acts are the real culprits for the increased involvement of girls in the criminal legal system (Chesney-Lind, 2004). They contend that on average girls’ actual behavior has changed very little.

I will posit the following ideas:

1. The labeling of girls as increasingly violent is widespread whether or not it is based on actual fact.

2. We need to listen to girls’ voices and contextualize their use and experience of violence. Girls’ violence needs to be contextualized rather than sensationalized.

3. There is a blurred boundary between girls as perpetrators of violence and girls as victims, survivors or witnesses of violence.

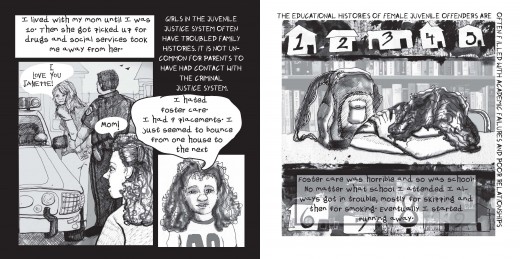

4. We need a better understanding of how and why girls end up in conflict with the law and what their experiences are once they get into the system.

Superintendent Charles Epps actually presents us with a valuable opportunity to do some truth-telling and to smash some stereotypes. Rather than demonizing young women we need to seek opportunities to better understand their lived realities. We need refrain from stigmatizing and further oppressing young women.