A new study suggesting that black men survive longer in prison is making the rounds on the internet and in the mainstream media. According to Reuters:

Black men are half as likely to die at any given time if they’re in prison than if they aren’t, suggests a new study of North Carolina inmates.

The black prisoners seemed to be especially protected against alcohol- and drug-related deaths, as well as lethal accidents and certain chronic diseases.

But that pattern didn’t hold for white men, who on the whole were slightly more likely to die in prison than outside, according to findings published in Annals of Epidemiology.

The study observed about 100,000 men between ages 20 and 79 who were held in North Carolina prisons between 1995 and 2005. Sixty percent of those men were African American.The full study and its findings can be found in the Annals of Epidemiology.

The study author David Rosen is quoted in the article saying: “For some populations, being in prison likely provides benefits in regards to access to health care and life expectancy.” Perhaps sensing that his findings might be misinterpreted or misused, Rosen sent an e-mail to Reuters adding:

“It’s important to remember that there are many possible negative consequences of imprisonment — for example, broken relationships, loss of employment opportunities and greater entrenchment in criminal activity — that are not reflected in our study findings but nevertheless have an important influence on prisoners’ lives and their overall health.”

Ah, the tyranny of social science… The question remains: “how ought we to interpret these study findings?” At Outside the Beltway, Doug Mataconis takes his shot at interpreting the findings of the study:

This isn’t surprising at all. First of all, when someone is in prison the opportunities for drug and alcohol abuse, which contribute significantly to bad health, are significantly reduced. Additionally, prison diets are much more regulated and, quite honestly, probably healthier than what someone in a lower-income group is likely to eat on the outside. Moreover, there isn’t much else to do when you’re behind bars other than exercise, which itself has health benefits. Finally, while prison health care doesn’t provide for regular checkups necessarily, it’s likely to be better than what the inmate could get on the outside. Meanwhile, on the outside, African-American men are more likely than the population as a whole to have drug and alcohol problems, the diet of someone who lives in a lower income group is likely to be high in fat and salt, and less access to health care.

It’s worth examining some of the claims made by Mataconis to see whether they are in fact credible. First, are African-American men more likely than the population as a whole to have drug and alcohol problems? A review of the literature about substance abuse by John Hopkins University reveals the following:

African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Alaskan Natives have higher death rates for cirrhosis of the liver relative to the total population.

Alcohol mortality rates are highest for African-American men, even though alcohol use tends to be more moderate for African Americans than for whites or Hispanics.

African Americans are more likely to report using illegal drugs on a weekly basis than any other ethnic group.

Hispanics are most likely to engage in heavy alcohol use, followed by whites and African Americans.

It appears that even if African-Americans use less alcohol and drugs, their mortality rate from the abuse of these substances tends to be higher than the general public.

Another claim made by Mataconis is that prison food may in fact be healthier than the food that lower income groups consume on the outside. Is there a way to assess whether this is true? Anecdotally, over the past few years, school lunches which many young people who are below the poverty line are subjected to have been found to be less nutritious than prison food. Good Magazine even created an infographic unfavorably comparing school lunches to prison food. The point being made is that BOTH types of food suck rather than prison food actually being good.

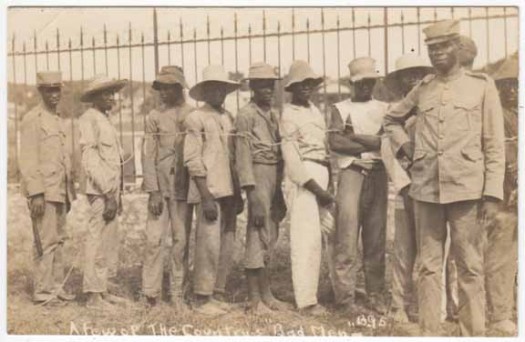

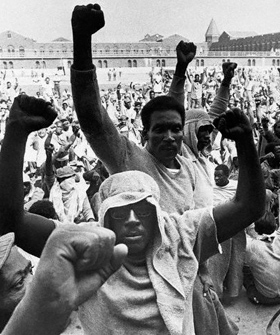

What should we make of all of this? Does this mean that more black men should be encouraged to spend time in prison to ensure longevity? Some people may in fact make the case that these findings are proof that prison is not as bad as it is made out to be. They will revive claims that prisons are in fact “country-clubs.” I want to make a few points about these potential claims. First, conditions in prison are brutal and awful. Only a disingenuous person would suggest that prisons are a good place to be. Second, the real “crime” is that the conditions in so many low-income communities are the equivalent and sometimes perhaps worse than prisons. Earlier this week, I wrote about the metaphor popularized in the 1970s of “America as the prison.” This seems particularly relevant as we consider the implications of the study.

Mataconis concludes his post with these words:

The policy implications here seem rather clear, the question is how to implement them. Long-term poverty in minority communities has been a problem in the United States for awhile, and nothing the government has done has seemed help at all.

I want to suggest that the only real attempt that was made to address long-term poverty in this country was during the Great Society era. However, it is clear from that experiment that “programs” are not what are needed to address poverty. People need and want employment. Yet the capitalist system is set up to ensure a perpetual underclass. It’s the law of supply and demand. There must always be an imbalance in order for capitalism to survive and thrive. In the past, I have had my students read a book titled “the Stakeholder Society” by Bruce Ackerman and Anne Allstot. The authors make a provocative proposal which is to provide each high school graduate with a one time cash payment of $80,000 once he or she reaches the age of 21. This would be offered with no strings attached. I like to use this book with students because it provokes debate and also surfaces a lot of the entrenched prejudices that we all hold.

I usually ask students whether the way for us to address poverty would be to give poor people money to live. “What if we gave each American $125,000 when they are born?” I ask them. This usually gets my students talking about concepts like the free rider issue or they make culture of poverty arguments (not usually recognizing them as such). I bring this up only to make the point that our country is rich enough and has it within its power to ensure that all of its citizens could work and earn a living wage. The greatest anti-poverty program is a LIVING WAGE JOB. Simple. The easy way to ensure longevity for black men in this country is NOT to lock them up in prison but to provide them with solid educational options and real employment opportunities. Simple.