Attica on My Mind…

This September is the 40th anniversary of the Attica Prison Rebellion and I have been thinking about how to best utilize this occasion to bring more focus to our current epidemic of mass incarceration. In my experience, a number of people recognize the word “Attica” and some smaller number may actually have a sense that it is a prison where a “riot” took place in the 1970s.

Luckily over the past few years, several resources have been developed to educate the public about the Attica Prison rebellion. I particularly like the “Attica Revisited” website which includes links to various Pacifica radio documentaries that shed a great deal of light on this history.

At the core of the rebellion were the prisoners’ demands for changes in prison policy including better medical care, better food, and more educational programs. The prisoners wrote a declaration of beliefs to the American people:

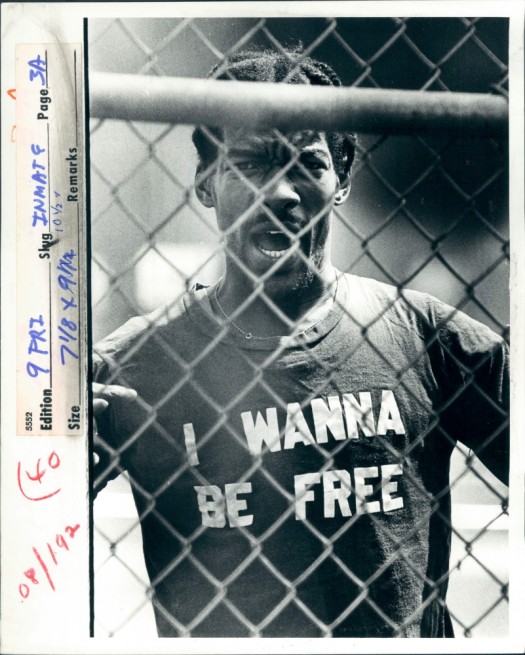

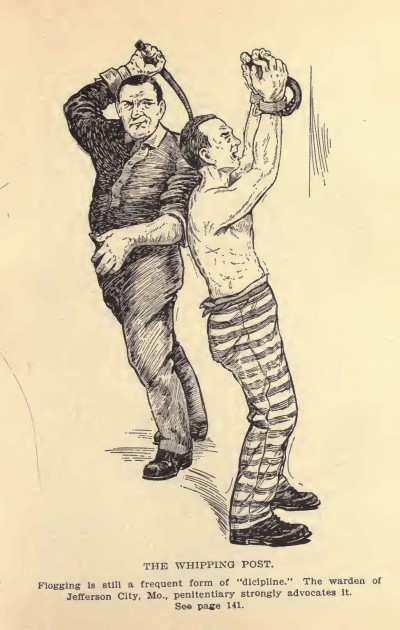

“WE are MEN! We are not beasts and do not intend to be beaten or driven as such. The entire prison populace has set forth to change forever the ruthless brutalization and disregard for the lives of the prisoners here and throughout the United States.”

It seems a particularly good time to recall Attica this week as prisoners across California show solidarity with the hunger strike organized by prisoners at Pelican Bay supermax by refusing meals. The Pelican Bay Hunger Strike is an example of non-violent resistance that may or may not focus the public’s attention to the injustices faced by the prisoners. In sharp contrast, in September 1971, the nation was transfixed by the Attica Rebellion as journalists and photographers documented the unfolding tragedy. Americans followed the events on television and when Nelson Rockefeller ordered state troopers to retake control of the prison, he unleashed a massacre. At the end of the episode, 43 people were dead, including 32 prisoners and 11 hostages. It was the television and photographic images that made Attica so resonant in the public’s imagination. The images exposed in black and white as well as in color what prison conditions were like in the U.S.

Leading up to September, I will write more about the circumstances and the significance of the Attica Prison rebellion. Additionally, I have decided that I will curate a photographic exhibition of the Attica Rebellion here in Chicago this September. I am honored beyond belief that the great John Shearer who was the only photographer allowed inside Attica during the assault by New York law enforcement in September 1971 will be providing some of his photographs for this community exhibit. Mr. Shearer was also the second African American staff photographer at Life Magazine following Gordon Parks. You can read a blog post that he wrote about Attica here.

I look forward to sharing more about my progress on the Attica photography exhibition with all of you in the coming weeks. Right now, I am confirming the location and the dates for the exhibition. It will be a youth-friendly space so I encourage those of you in Chicago or nearby to arrange to bring your students and your youth groups to the exhibition. More details will be forthcoming.

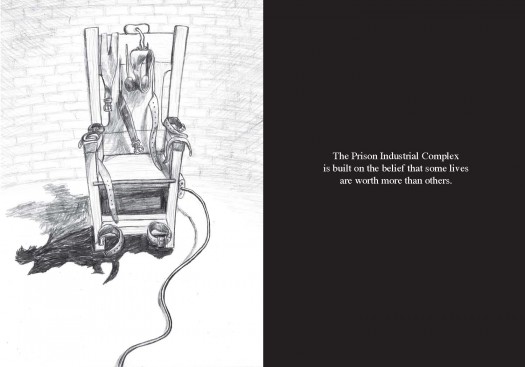

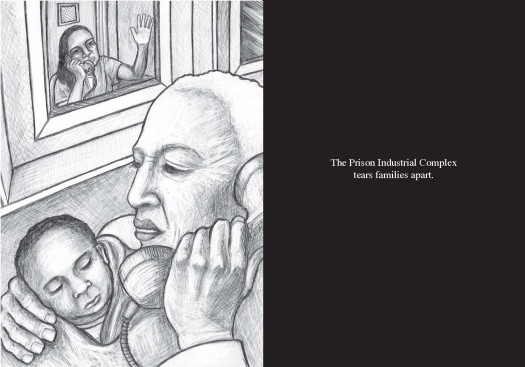

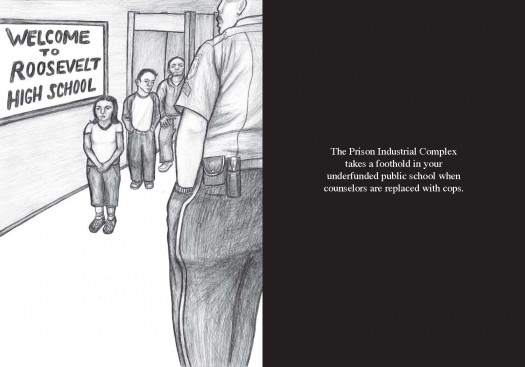

Note: Zine makers are invited to create publications that we can share with people who attend the exhibition. Please e-mail zines to [email protected].

Update: Here is some information about the upcoming photographic exhibition in September.