I am blessed to meet amazing people through the work that I do. I was lucky to make an e-connection with Nancy Heitzeg through Daily Kos some time ago. As of this month, I am proud to be one of the new contributing editors of the great series that she co-launched over at the Daily Kos called “Criminal Injustice Kos.” Nancy was kind enough to submit this piece to Prison Culture. It first appeared as a CIK diary. It is as powerful today as when it was first published at Daily Kos.

Nancy A. Heitzeg is a Professor of Sociology and Race/Ethnicity at St. Catherine University. She blogs as soothsayer99 and is the Editor of Criminal InJustice Kos is a weekly series devoted to taking action against inequities in the U.S. criminal justice system. Criminal InJustice Kos is published every Wednesday at 6 pm CST. The following piece was written after another recent trip to Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola – Dr. Heitzeg has previously written about LSP Angola in “Visiting a Modern Day Slave Plantation” Interview with Angola 3 News Part I January 2010 and “The Racialization of Crime and Punishment” Interview with Angola 3 News Part II February 2010.

Nancy A. Heitzeg is a Professor of Sociology and Race/Ethnicity at St. Catherine University. She blogs as soothsayer99 and is the Editor of Criminal InJustice Kos is a weekly series devoted to taking action against inequities in the U.S. criminal justice system. Criminal InJustice Kos is published every Wednesday at 6 pm CST. The following piece was written after another recent trip to Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola – Dr. Heitzeg has previously written about LSP Angola in “Visiting a Modern Day Slave Plantation” Interview with Angola 3 News Part I January 2010 and “The Racialization of Crime and Punishment” Interview with Angola 3 News Part II February 2010.

Criminal InJustice Kos appears every Wednesday at 6 pm CST at Daily KOS

How To Convey The Horror????

by soothsayer99

These pages are written in no spirit of vindictiveness, of all who give the subject consideration must concede that far too serious is the condition of that civilized government in which the spirit of unrestrained outlawry constantly increases in violence, and casts its blight over a continually growing area of territory. .. No comment need be made upon a condition of public sentiment responsible for such alarming results….

Ida B.Wells -Barnett , A Red Record, 1895

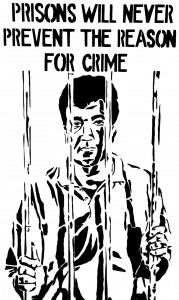

Every week in Criminal InJustice Kos, we try to further awareness of the racist, classist monstrosity that is otherwise known as the prison industrial complex. This beast encompasses the very law itself, as well as a vast correctional enterprise ranging from police to prosecutors to correctional officers to private corporate interests that profit from a seemingly endless supply of mostly black and brown neo-slave labor.

Often we make our case, as I do every day in one university class or another, with “facts” and statistics and cold data and, occasionally with a specific story of some egregious abuse or injustice..

But how to convey the under-lying aggregate horror that haunts us — that prison is a genocide, a legalized outlawry, another piece of that red record??

How to pierce through the plethora of numbers and public justifications and lies to expose this for what it really is — a raw ugly racist wound that can never be healed but only excised??

How to make you feel the urgency, the pain, the devastation of families and communities, and the decimation of a people???

And yes how to persuade you to join us in making it stop???

We use the words – slavery. lynching — we write and speak about the racist and class-bound criminal injustice system, the fact that slavery is not abolished by the 13th Amendment, that the promise of due process and equal protection and voting rights have all been undone — here, here and here..

But dare we explore the depths of what these words mean?? The ramifications then of what we must do now??

Today I am going to say it all plain — yes in words but mostly in feelings, in stories, in emotions, in what I have experienced.

I am asking you – with my whole heart – to really look and not turn away….

Prison in the United States is a direct outgrowth of slavery, a system designed and re-designed to exploit a largely black captive labor force — first with prison as plantations and convict lease labor all supported by legal segregation and extra-legal lynching, and then later as the prison industrial complex.

But these systems — all of them – have always about more than mere economic exploitation of mostly black labor. They are about a people as property subject to the most brutalizing punishments — the lash, the bit, the bell – collar, the spur, the chain , the most degrading sexual exploitations and mutilations – rape, castration, medical experimentation without benefit of anesthetic, and endless evolving efforts to dominate and regulate the reproduction of black and brown people. All of it — slavery, convict lease, lynching morphed into state-sponsored capital punishment, plantations turned into the prison industrial complex — is about, as Dorothy Roberts aptly puts it, Killing The Black Body.

Yes, poor whites, other people of color and white women are also swept up in these systems of ruthless control. Beaten brutalized raped aborted lynched imprisoned. They always have been. But in the paradigm of punishment, the loci of domination have always been built upon that peculiar legacy in this country of controlling the black body.

Prison remains a site where black and brown reproduction is stymied and where sexual exploitation persists. Just as the reproduction of black and brown women was regulated via forced sterilization and both positive and negative incentives to suppress pregnancy,so too the prison serves as a site of pseudo-castration, a way of cutting off a large segment of the population from sexuality, family and reproduction. Look at the numbers and do the math — I in 9 Black men between the ages of 24 -35 in prison, 1 in 15 Black men over the age of 18, 1 in 36 Latinos, 1 in 100 Black women between the ages of 35-39 in prison. Future generations denied; current generations disrupted as 1 in 15 Black youth have at least one parent in prison.

Dorothy E. Roberts makes this observation:

Over the last two decades, the welfare system, prison system, and foster care system have clamped down on poor minority communities, especially inner city black neighborhoods, thereby increasing many families’ experience of insecurity and surveillance. Welfare is no longer a system of aid, but rather a system of behavior modification that attempts to regulate the sexual, marital, and childbearing decisions of poor unmarried mothers by placing conditions on the receipt of state assistance. The federal government encourages states to implement financial incentives that deter welfare recipients from having children and pressure them to get married.

The contraction of the U.S. welfare state, culminating in the 1996 federal welfare reform legislation, paralleled the expansion of prisons that stigmatizes inner-city communities and isolates them further from the privileges of mainstream society. Radical changes in crime control and sentencing policies led to an unprecedented buildup of the U.S. prison population over the last thirty years. By the end of 2002, the number of inmates in the nation’s jails and prisons exceeded two million. Today’s imprisonment rate is five times as high as in 1972 and surpasses that of all other nations. The sheer scale and acceleration of U.S. prison growth has no parallel in western societies. African Americans experience a uniquely astronomical rate of imprisonment, and the social effects of imprisonment are concentrated in their communities.

Beyond the suppression of black and brown reproduction, the prison is the current extension of the long ugly obsession with black sexuality and its ultimate expression in violence and mutilation. Slavery, extra-legal lynching and now the prison are marked by hegemonic white supremacist masculinity that has always derived its power from the “white gaze” and attendant violence in the form of rape sexual mutilation and castration. The wounded black man — emasculated literally as was the case in most lynchings or figuratively via the prison experience – and the ravagable black woman are endlessly now on naked display, subject to cavity searches at will, sexual assaults by other inmates and guards, sexual objects still.

It is no mere historical coincidence that observers of both capital punishment and the prison draw a straight line from the physical and sexual terrorism of lynching to the modern death penalty and mass incarceration. In From Lynch Mobs to the Killing State, Ogletree and Sarat clearly make the case that lynching only subsided as states took over the task of disproportionately executing errant blacks for the white mobs. Especially of course those accused of raping white women. These racial disparities are undisputed and the subject of Supreme Court cases ranging from Furman to Coker to McKleskey. And prison itself performs, amongst other functions, metaphoric castration and lynching.

James Cone, in The Cross and the Lynching Tree notes this:

It’s in the prisons. It’s in prisons. It’s all over. Prisons, I would say, is the most prominent. Crucifixion and lynchings are symbols. They are symbols of the power of domination. They are symbols of the destruction of people’s humanity. With black people being 12 percent of the US population and nearly 50 percent of the prison population, that’s lynching. It’s a legal lynching. So, there are a lot of ways to lynch a people than just hanging ’em on the tree. A lynching is trying to control the population. It is striking terror in the population so as to control it.

No one wants to talk about this ugly under-current. But it is there. Undeniably. Every time I go to Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, I see it there on full display. The eternal white male gaze. The countless “neutered” black men, the ones that it is safe for the public to encounter now, waiting without choice on Warden Cain or demanding white women in the gift shop/museum. The stories that emerge along the tour — of the closure of the outdoor visiting park because — gasp –inmates had sex with their wives and girl friends. The fact that inmates on lock down must now walk their 1 hour of exercise in those wire dog kennels with hands cuffed to a waist shackle, because allegedly an inmate flashed his “manhood” at a female guard in the tower.

This time there I saw another dimension. Our tour guide, the head of Classification at Angola, decided to give us — me and 20 female, mostly white students – what he described as “something extra”. “Something extra” not part of the typical tour. So without warning, we were taken into cell blocks on both Death Row and Camp J, the segregation facility where 20% of the population is on 23 hour a day lock down. We were taken to see the wild wounded black men in cages, those to be killed like Derrick Todd Lee, the convicted serial killer and raper of white women whom we were pointedly introduced to, and those who would die there anyway in a longer but state-sponsored death nonetheless. This incident was designed partly as threat to us renegade damn yankee abolitionist women, and partly as a taunt to the inmates about women they never would have. They were offered up to us and we to them under the voyeuristic watch of that omnipresent white male gaze. We were disrespected by no inmates and did our best to disrespect none in return — but being there itself was, wasn’t it?? But it was clear that we were — all of us – the ritualized objects of institutionalized sexual exploitation and psychic assault.

They owned us all that day – in that most disgusting display of white supremacist masculinity personally ever encountered. And the horror of that can only be felt like a kick to the stomach – it is more than mere words can convey.

Lock Down Raw — the real deal.. This is what prison, bottom line, is all about.

Despite these gruesome underpinnings, we speak of prison in such causal ways, as if it was necessary, as if it would protect us, as if it were sometimes designed to improve opportunities for inmates. So benign and if sometimes brutal, well then deserved and at best so sugar-coated. A recent article in the New York Times, Enlisting Prison Labor to Close Budget Gaps makes this claim. Rather than asking the obvious logical question — would reducing prison populations be the best way to cut correctional costs??, The Times article goes on to offer a multitude of legitimations and justifications for increased exploitation of inmate labor. Increased use of inmate labor not only alleviates state budget crises — it also according to “experts” offers inmates marketable skills.

Prison labor — making license plates, picking up litter — is nothing new, and nearly all states have such programs. But these days, officials are expanding the practice to combat cuts in federal financing and dwindling tax revenue, using prisoners to paint vehicles, clean courthouses, sweep campsites and perform many other services done before the recession by private contractors or government employees.

In New Jersey, inmates on roadkill patrol clean deer carcasses from highways. Georgia inmates tend municipal graveyards. In Ohio, they paint their own cells. In California, prison officials hope to expand existing programs, including one in which wet-suit-clad inmates repair leaky public water tanks. There are no figures on how many prisoners have been enrolled in new or expanded programs nationwide, but experts in criminal justice have taken note of the increase. ..

“Using inmate labor has created unusual alliances: liberal humanitarian groups that advocate more education and exercise in prisons find themselves supporting proposals from conservative budget hawks to get inmates jobs, often outdoors, where they can learn new skills. Having a job in prison has been linked in studies to decreased violence, improved morale and lowered recidivism — but most effectively, experts say, when the task is purposeful.

Well cleaning up roadkill might be an improvement over spending 23 hours per day in a cell, but the notion that prison training programs do anything to develop marketable skills for inmates is a damn lie..These inmates are not being trained to take your job or any job — they are doing our “dirty work” for pennies on the hour..

Much of this work is unskilled manual labor or assembly work. These are not marketable skills and certainly do not offer inmates any new advantage when faced with employers already disinclined to hire convicted felons. Educational and vocational programs are disappearing and those that remain offer inmate training that is minimal and often obsolete.

Two years ago, I was invited to give a speech at the Educational Achievement Recognition Ceremony at MCF – St. Cloud, the state’s level four prison for younger ( including juveniles certified as adults) and first time offenders. In addition to the stress of imagining how to construct an uplifting message for an incarcerated population, some of whom would be doing life; there was the sadness at who was there and what achievements were to be celebrated. Young black male. Some of the newsworthy crime story cases were there — an alleged “gang member” sentenced to life at 17, even with doubts about his direct involvement.. prosecuted to the fullest by then Hennepin County Attorney, now Senator, Amy Klobochar.

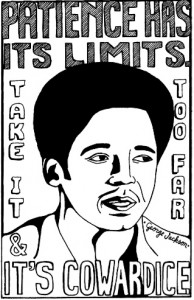

The theme of the program was the George Washington Carver quote: “Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom”, and in the midst of that tragic irony, I did my best to try to be uplifting mentioning great prison writers – to the chagrin of prison staff – Leonard Peltier and Mumia Abu-Jamal, Assata and Sundiata, Angela Davis, Huey P Newton and Stanley “Tookie” Williams, Piri Thomas and Wilbur Rideau, Malcolm X and Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Hoping that a name would be familiar or strike a chord and somehow inspire.

And then the awards to the graduates, GEDs. Certificates in Masonry and Barbering and Wood-working. Over and over and over. That was all. Skills that might get you a better position working with MNCORR, when you were transferred out to Stillwater or Oak Park Heights.

Yes it good that there are opportunities for activity. Yes it is good that there are Educational Recognition Ceremonies in the gym with speeches and cake and an inmate band and yes even family and friends. But I thought of the graduation ceremonies I attend as a professor, where Bachelors and Masters and PhDs are awarded, with great and literal pomp and circumstance, with dignitaries and faculty in full academic garb, with so much limitless promise. This seemed so meager, so little and so late.

As I was leaving, I was given a gift, made by inmates in the wood-working class. While the wood work was exquisite, it took me some time to figure out what it was. It was a cribbage board that slid out from an elaborate train. A cribbage board – I hadn’t seen one since my grandfather, who was a player, died over 25 years ago, These are the skills taught in the 21st Century Minnesota Prison system, in many respects the best the nation has to offer. Trains, cribbage boards, items of a by-gone era, produced with a skill set that is approaching obsolescence. Made in wood shop by young black urban males, that no system took the time to teach when they were actually free.

Another generation of wounded black men, with no end in sight.

And I wept.

I have never really been to prison – I mean locked up in a cell unfree to go.

There are contributors here to CIK who have been, as well as those who go in to serve, to share their knowledge of the law with incarcerated peoples.

You all have my undying respect and gratitude for your willingness to share your knowledge, your stories, and your expertise. Thank you.

I have a only glimpse of prison and that glimpse both verifies and surpasses anything I have read in books, anything that can be documented with data.

But maybe because I was not captive to it or focused on the specifics of legal salvation for some, I was able to see through to the core of it and take away the dirtiest secrets because I was free to bear the pain. Free to be a witness.

Yes prison is a slavery — in all the senses that the word conjures – racist sexist classist degrading dehumanizing rape mutilation genocide. It is a needless stealer of bodies, of labor, and of lives.

It must end..

There can be no talk of racial justice this country while this abomination persists. There is no reforming, fixing, remedying of anything while this remains. Indeed, there can be no talk of justice at all, until we confront what Joe Feagin has rightly named, “slavery, unwilling to die.”

There must, finally, be Abolition.

I wish i had the words to convey the full horror of what I have seen, what I know to be true.

I wish I knew how to move you to Rise Up!!! – Rise Up in Resistance! to this.

I can only pray, as Sister Helen Prejean does in the preface to The Death of Innocents: An Eyewitness Account of Wrongful Executions,

“I hope that what you read here sets you on fire.”

Nancy A. Heitzeg is a Professor of Sociology and Race/Ethnicity at St. Catherine University. She blogs as

Nancy A. Heitzeg is a Professor of Sociology and Race/Ethnicity at St. Catherine University. She blogs as