Guest Post: Fieldnotes from la casa del Diablo

This is a guest post from my friend Dr. Laurie Schaffner. Laurie is a professor of Sociology with appointments in the gender and women studies program as well as the criminal justice program at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Laurie is the author of the excellent book “Girls in Trouble with the Law” and many other publications. She also serves as an adviser and ally to Girl Talk.

I thank Laurie for sharing her notes with Prison Culture.

__________________________________________________________________________

Since 2007, I have been spending time with folks involved in the juvenile legal system and the broader youth advocacy movement in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. In 2006, the state congress of Jalisco passed a new reform law. The idea of the change was to move from a paternalistic tutelage approach to infusing the system with a more transnational children’s rights perspective. At that time, I was curious to see how this new approach would come about. Interestingly, but not unpredictably, it was not working smoothly for either the traditionalists working with youth who were convinced that young people who commit crimes should be punished and rehabilitated, or us youth advocates who were persuaded that the legal system should not be utilized at all when addressing the social problem of vulnerable youth in crisis.

What follows are raw field notes. Field notes are a tool of witness that people, such as academics and poets and activists, use when they want to write down what they see when people are doing what we do—working, living, learning—what we do “on the ground,” “in real life.” They are useful to use later as “data” – to analyze and make claims about injustice or social trends, or to provide details for fiction and history.

I use //// to parenthize my own private thoughts, musings, things-to-do notes and the like. All field notes are only slightly edited, and I provide no interpretation. I will leave the analysis (your impressions) up to you at this point of the project.

I go back and forth from Spanish to English with no translation. I hope this is not too much of a challenge for readers. It can take years to learn each other’s languages, but often a brave and fruitful endeavor. Sometimes I find books that go into a French quote or reference in the middle of the page and get pretty irritated but it makes me realize how monolingual I am and that the norm in the rest of the world is to easily glide back and forth among several languages.

Thanks to William Schaffner and Memo Konrad for giving me good suggestions. May Betty Foster rest in peace, and a big huge welcome to Aleeya in the family!

* * *

21 enero 2008 01 Ninas en conflicto con la ley El Tutelar

1600 hours to 2200 hours

Image 1. My co-investigadora

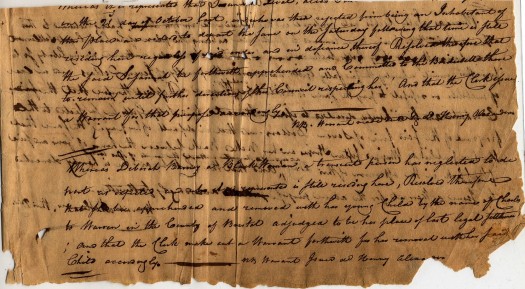

Coco and I went to meet the Director of the short-term detention facility for youth located in Guadalajara, known as el Tutelar. At that time, it was Licenciado Sergio Saavedra Medina, Director of the Tutelar, (according to his tarjeta: Director del Centro de Observacion, Clasificacion, y Diagnostico del Estado), which is actually (since the law changed) the Diagnostic Center.

Image 2. The exact name and address of el Tutelar

We decided our primary mission for this visit was multiple, but not exhaustive:

• To figure out where it was and what it was

• To introduce ourselves

• To get some basic information, such as, how many girls are there, and for how long?

• To find out what programs they are offered

• To figure out how we could participate in what is ongoing.

Coco and I met in Juarez Park in central Guadalajara to take a bus to the Tutelar (Ruta 633) /// which I realize stops like two blocks from my house///

We were both dressed a little more formally than for street outreach work with youth and it took like an hour to get there. Actually it didn’t really get there, it dropped us off and we had to walk about six long blocks before we found it.

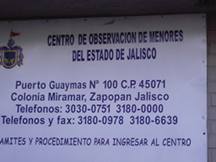

The Tutelar is a huge multi city-block facility, walled off by one chain-link fence topped with shiny new barbed wire, the kind with little knives in it ///find out later it is called razor wire/// at the street level. About ten feet in from that first fence is another brick wall topped with barbed wire as well. Like most penal structures, it looks as if you couldn’t escape without inside assistance.

Image 3. A sign on the perimeter of el Tutelar

Also similar to detention centers world-wide, el Tutelar is set apart from residential and commercial activity on purpose—juvenile delinquents, out of sight-out of mind. There is a huge sort of warehouse, parking, storage space for ///el ayuntamiento? /// bordering on one side (Calle Puerto Guaymas) and what I thought was Periferico Sur on another. We didn’t circle the entire structure because it was so large, the street was all torn up, and we didn’t really have time.

That was because, although we arrived on time at 1600 hours for our appt, the Director had been “called away on an emergency.” The clerk called him up and told him we were there and then she said he was “on his way and would arrive in approximately one half hour.”

///which didn’t make sense—if he’d been called away on an emergency, wouldn’t he just not have been available?///

We decided to walk around the perimeter during the wait, but the Tutelar is too large to circumambulate ///circumnavigate?/// in one half hour.

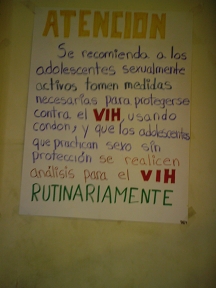

Before we departed, we photographed the wall of announcements in the “lobby,” especially one obviously (?) made by a youth warning other “sexually active youth” to get tested for AIDS (see photos).

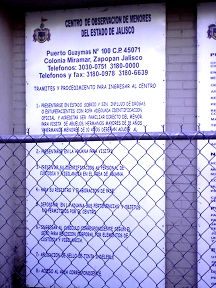

Image 4. Rules for entering the detention center.

Hard to read, but the list of rules for what you can and cannot bring into the juvenile facility includes don’t bring in chewing gum, candy, weapons, pornography, alcoholic beverages, glass containers, sharp items; don’t wear platform shoes, (for men: earrings in any part of your body; for girls and women only: don’t wear earrings anywhere but in your earlobes, skintight clothing, shorts, miniskirts,) “ropa sport cholo;” however, you can bring in toilet paper.

Image 5. More rules for entering el Tutelar

These images, obviously not taken by a professional photographer (taken by me, actually) are difficult to read in this reproduction. More rules here include orders to present yourself sober and not under the influence of any mind-altering substances, with appropriate clothing, identification, and proof or your relationship to the minor in detention. The other rules are bureaucratic in nature: secure proper permission for the visit, your papers must have the proper seals and stamps in ink, and the like.

Image 6. Sign made by youth in lobby of el Tutelar

I liked this sign because it looked like maybe the youth made it.

First of all, of course, you have to speak to an armed guard, give him your paperwork, and (hopefully) get “buzzed in. Hopefully, because any visitor can be refused entry at any time for any arbitrary reason, unless you have a written order from your boss’ boss.

A small room, maybe 8 feet by 10 feet, the lobby at the Tutelar Is equipped with a huge Coca Cola machine, a bulletin board, and 4 chairs. As we were waiting initially, a group of people ///a family?///came walking in.

One man seemed about 50 years old and had long black curly hair, old ill-fitting jeans, and a kind of starter jacket—old, turquoise and black parachute silk material. I sort of thought he seemed like a Mexican hippy from back in the day. Of the four persons, he carried himself as the most entitled, not hunched, tentative, or humble. He spoke last, double-checking information in a clear voice. The woman/mother of the detainee spoke first, “Disculpe, podemos traer una cobija para //nuestro hijo///couldn’t hear exactly how she said it///

The mother appeared as a 30-ish senora with slacks, sweater, nothing matching, working class or poor, black ponytail. Her daughter //detainee’s girlfriend?// was dressed straight from the Saturday Calle Javier Mina tianguis—skintight jeans, large sneakers, babydoll t-shirt, après-ski jacket (baby doll, fake down, furry-lined hood), hair in ponytail, black eye-makeup. The third person was an older man, maybe grandfather. Several questions and answers were exchanged, something like this:

MOTHER: Podemos traer cobija aqui para el detinido? Podemos traer ropa tambien?

CLERK: Les dan cobijas y comida. Puede traer ropa, pero no mezclilla, color negro, azul, ///I can’t remember what other colors exactly, but there were definite colors not permitted//

DAUGHTER: Ah, yo se, tenemos aquellos pantalones cafes podemos llevarle.

HIPPY/OLD SCHOOL MAN (FATHER?): Hasta que horas estan abiertos? Cuando abren? Todos los dias? Aqui dejamos la ropa?

///I was thinking, how pathetic and unfair—they worry about bringing blankets, clothes, and food to their detained children. Probably the young person told them during visiting hours, “It’s FREEZING in here at night and I haven’t changed my socks in two weeks.” He probably told them he’s hungry all the time. Then I was remembering when Raul stabbed Aunt Margaret in Cuernavaca in 1976, how we had to bring sheets, blankets, nightgown, and food to her in the Red Cross. Same deal with Daddy in the carcel in Guatemala City///

El Lic. shows up and invites us into his office and begins to inform us of who he is and what happens here in el Tutelar.

This is a Centro Diagnostico, not a long-term facility, so the youth stay “only” 90 days while they are “diagnosed” and it is decided where they should go (home? La Granja ? (which is the long term facility).

The Tutelar, as it is still called, has 288 beds. The youth residents’ areas are formed into what everybody called modulars. Each of the 8 modulars has its dormitorio with 36 beds, bathrooms, cocina y sala; and, apparently, their DVD and television. Module 2 is for girls, Modules 3-4 are for “internos adolescentes libres—6 meses” which are youth that can come and go somehow. Modules 5-9 are for boys.

At that time, there were five girls assigned to this Centro Diagnostico, but one was away in the hospital porque ella dio luz. She will return with her baby. There were a total of 151 boys at the time of this visit (but the numbers changed throughout the interview—more about that later).

We asked, “Where are all the girls at? There are only five girls in the Guadalajara area in detention?” We were informed that “all the girls are at La Granja.”

El director emphasized that all youth can meet with the Director (himself) at any time. He seemed proud or wanted to have it be known that “his door is always open” ///which of course made me immediately think that he never allows anyone in there///

Next, we were told that there is a chronograma de actividades that includes obras de teatro, futbol, actividades de artes and culturales, and deportivas

I remember (we were both writing fast and furious during the interview) he ran down this daily schedule that was like, get up, bathe, make beds, have breakfast, go to school, recreation, can bathe again, TV, dinner, groups, sleep.

///As soon as he said that the youth can bathe twice a day, I thought to myself, “This guy has no idea what he’s talking about or what goes on here”///

We are told that the groups that come in regularly include Alcoholics Anonymous and religious visitors.

The youth are separated by various classifications that include edad, sexo, aptitudes, actitudes, y antecedentes.

Each youth has a team assigned to him/her: psychology, social work, teacher, and a preceptor tecnico who accompanies, orients, and guides the young person through the system experience.

They all have access to doctors—medical, psychological, and psychiatric.

He said that 90 percent of the youth are here for “el robo.”

Sounds great! ///NOT/// He made it seem like a pretty nice place with great people.

Image 7. Workers taking a break

Then he said there was no way we could get a tour of the residents’ units/modulars, observe a program, or meet with any staff.

* * *

8 May 2008

After meeting with his boss’ boss, we return for the royal treatment with a complete tour and access to every inch of the Tutelar at our disposal. Here are abridged notes from that first day on the inside.

It is HOT! A sweltering, go anywhere you can find air conditioning or be in a pool kind of day, the luxuries very few Tapatios can actually enjoy. Trying to beat the heat, we show up at about 0800 hrs.

We are directed to another person, a woman, Director of a Sub-division, Facilities Management. She graciously takes us through the process of leaving all our bags, going through security alarm systems guarded by people with guns (which also included being in a private room with a woman guard who “pats you down”) and sort of opens to another door which deposits you at the beginning of a long walkway leading to the modulars and other buildings.

We asked to see the school, so we began there. The school consisted of about three cinder-block structures, approximately 15 feet by 20 feet each, with open air “windows” built into the brick walls.

A) it was HOT! The schoolrooms felt like kilns inside.

B) There was nothing but some chairs and tables, a few (broken down?) old computers, a library that consisted of about 20 books and a primary school curriculum

C) There were no youth anywhere in any classroom

///I believe the Mexican Constitution requires free mandatory public education for all Mexican citizens—check this////

The “teacher” seemed like a sweet little old lady, she explained that they had no books or curriculum, that the majority of boys could not yet read, most of the boys “just slept in and played futbol or went to job training,” and she was about to retire.

We move on to see the main kitchen where the meal are prepared, we tour the workshop areas where boys are learning to repair things—old broken down stoves, bicycles, refrigerators ///there was actually a whole room full of broken shit for them to learn on/// met with the social work department, the medical center, the legal department, the counseling department, and much more. …

We have pages of notes detailing this ethnographic and interview data, but for this short entry I wanted to share one particular observation that has haunted me for years.

As we are walking through the modular living units, I ask, “What about the gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, transitioning youth? What policies and procedures do you have in place to guarantee their rights and freedoms?” ///We had already requested a copy of the Policy and Procedures Manual///of course, one was never produced for us.

We were informed that there were no homosexuals here and that that kind of behavior was not permitted.

We continued our tour of the living spaces and began our tour of the medical facilities. We met one young man laying in a bed with a stomach ache, and another in a chair in the hall with a headache. We go through one room and into the next room that has six beds, six boys, all decorated with flowery blankets, lots of stuffed animals and clothes of shiny or flowery fabric strewn about, and a TV blaring. Six young boys look up at us in surprise and curiosity—all wearing make-up, skirts, dresses, doing each other’s hair, looking quite comfortable, actually. Relaxed, talking, comraderie, laughter were my first impressions.

I think I was as astonished as they were. I know our tour guide was taking aback, I think she forgot that they were here. All I could think was, “How could you tell us in one breath that there are no sexual subordinate groups here and then walk us through this module?” Then, of course, I realized they were housed in the medical modular and became worried for their emotional and psychological well-being.

Pues, ni modo, the tour continued on, and as all good research goes, one is left with more questions than which they began…