Books about Incarceration for Teens…

Last week, I received a moving e-mail from a young mother who has a 15 year old son. She wrote to me about some of her struggles with her son. She made a specific request: Could I provide her with a list of books that her son would find entertaining while also addressing the experience of incarceration? Thankfully, I am an avid reader of young adult fiction (YA) and I have indeed come across some books with incarceration themes that I could recommend. I sent her a list earlier this week and thought that other readers of this blog might also be interested in some of these titles.

My hands-down best YA title about incarceration that I read this year was Lockdown (2010) by Walter Dean Meyers. I just love Meyers because he is a master at writing in the voice of young Black boys. The book is best for high school age youth. Here is a short review from Booklist:

Myers takes readers inside the walls of a juvenile corrections facility in this gritty novel. Fourteen-year-old Reese is in the second year of his sentence for stealing prescription pads and selling them to a neighborhood dealer. He fears that his life is headed in a direction that will inevitably lead him “upstate,” to the kind of prison you don’t leave. His determination to claw his way out of the downward spiral is tested when he stands up to defend a weaker boy, and the resulting recriminations only seem to reinforce the impossibility of escaping a hopeless future. Reese’s first-person narration rings with authenticity as he confronts the limits of his ability to describe his feelings, struggling to maintain faith in himself; Myers’ storytelling skills ensure that the messages he offers are never heavy-handed. The question of how to escape the cycle of violence and crime plaguing inner-city youth is treated with a resolution that suggests hope, but doesn’t guarantee it. A thoughtful book that could resonate with teens on a dangerous path.— Ian Chipman

The next book that I recommended is titled “Holes (1998)” by Louis Sachar. This is a book about a young man who is sentenced to boot camp. I will include the Booklist review below. However I really disagree with the reviewer about the final part of this book. It is the realism of the ending that really saved the book for me. My godson absolutely loved this book. He read it when he was in the 7th grade and I think that it was completely age appropriate for him. He has since recommended it to other friends.

Middle-schooler Stanley Yelnats is only the latest in a long line of Yelnats to encounter bad luck, but Stanley’s serving of the family curse is a doozie. Wrongfully convicted of stealing a baseball star’s sneakers, Stanley is sentenced to six months in a juvenile-detention center, Camp Green Lake. “There is no lake at Camp Green Lake,” where Stanley and his fellow campers (imagine the cast from your favorite prison movie, kid version) must dig one five-by-five hole in the dry lake bed every day, ostensibly building character but actually aiding the sicko warden in her search for buried treasure. Sachar’s novel mixes comedy, hard-hitting realistic drama, and outrageous fable in a combination that is, at best, unsettling. The comic elements, especially the banter between the boys (part scared teens, part Cool Hand Luke wanna-bes) work well, and the adventure story surrounding Stanley’s rescue of his black friend Zero, who attempts to escape, provides both high drama and moving human emotion. But the ending, in which realism gives way to fable, while undeniably clever, seems to belong in another book entirely, dulling the impact of all that has gone before. These mismatched parts don’t add up to a coherent whole, but they do deliver a fair share of entertaining and sometimes compelling moments. -— Bill Ott

Another recommendation from the canon of Walter Dean Meyers is Monster (1999). Here is a review from Booklist:

Myers combines an innovative format, complex moral issues, and an intriguingly sympathetic but flawed protagonist in this cautionary tale of a 16-year-old on trial for felony murder. Steve Harmon is accused of acting as lookout for a robbery that left a victim dead; if convicted, Steve could serve 25 years to life. Although it is clear that Steve did participate in the robbery, his level of involvement is questionable, leaving protagonist and reader to grapple with the question of his guilt. An amateur filmmaker, Steve tells his story in a combination of film script and journal. The “handwritten” font of the journal entries effectively uses boldface and different sizes of type to emphasize particular passages. The film script contains minimal jargon, explaining camera angles (CU, POV, etc.) when each term first appears. Myers’ son Christopher provides the black-and-white photos, often cropped and digitally altered, that complement the text. Script and journal together create a fascinating portrait of a terrified young man wrestling with his conscience. The tense drama of the courtroom scenes will enthrall readers, but it is the thorny moral questions raised in Steve’s journal that will endure in readers’ memories. Although descriptions of the robbery and prison life are realistic and not overly graphic, the subject matter is more appropriate for high-school-age than younger readers.— Debbie Carton

I read Paul Volponis’ Rickers High (2010) this summer and I found it gripping and engaging. It has stayed with me all of these weeks later. I highly recommend it for young men of high school age. Here’s the booklist review:

Recasting his specialty-press debut novel, Rikers (2002), for a younger audience, Volponi tracks a juvenile offender’s final 17 days in the New York correctional facility. Though arrested just for telling an undercover cop where to buy weed, Martin has spent five months at Rikers waiting for his case to come up. The experience has made him a canny observer of the prison ecosystem, good at keeping his head down and steering clear of gangs, extortion schemes, brutal correction officers, and other hazards . . . mostly. The author draws authentic situations and characters from his six years of teaching at Rikers, and though his scary cautionary tale is less harrowing than Adam Rapp’s Buffalo Tree (1997) or Walter Dean Myers’ Monster (1999), it is nevertheless an absorbing portrait of life in stir. In the end, Martin walks out on plea-bargained probation, bearing both inner and outer scars. Rare is the reader who won’t find his narrative sobering. — John Peters

The reviewer mentions the book “The Buffalo Tree (1997)” by Adam Rapp. I read that book about 10 years ago. While I personally loved it, the young mother who wrote to me said that her son has some literacy challenges. Because of this, I refrained from recommending books that might prove challenging in terms of language. If you are a grown person or if you are a teenager who likes to be challenged by language, then I highly recommend that you read “The Buffalo Tree.” It is a searing portrayal of life inside a juvenile detention center.

I read “Boot Camp (2007)” by Todd Strasser last year. It was excellent and felt very realistic. I liked this book more than I did “Holes.” I imagine that young people from 10th grade up would also very much enjoy “Boot Camp.”

Louis Sachar’s Holes (1998) described a juvenile detention camp with tall-tale trappings. For a somewhat older audience, this documentary-style novel tackles similar “boot camps” without the fablelike buffer, delivering a troubling glimpse of what might go on in such camps (and backing it up with an author’s note and sources). Garrett, 15, is trapped in the “secret prison system for teenagers” when his controlling parents, enraged by his affair with a teacher, are lured by the promise of a boot-camp brochure: “The child who returns from the Lake Harmony experience is the child you always knew you had.” Once at the camp, Garrett endures a battery of brainwashing techniques, including physical abuse, and eventually meets two other desperate teens who want to escape. Some plot elements don’t add up; it’s hard to believe, for instance, that the one supportive adult Garrett encounters—a warden—would let the camp continue without blowing the whistle. But as in Strasser’s Give a Boy a Gun (2000), the real-world issues will hit a nerve.— Jennifer Mattson

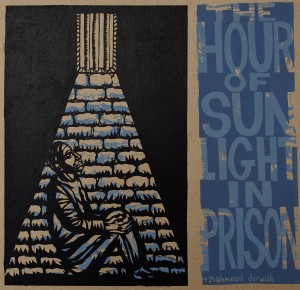

My final suggestion was a book titled “A Question of Freedom: A Memoir of Learning, Survival, and Coming of Age in Prison (2010)” by R. Dwayne Betts. I usually avoid recommending non-fiction books to high school students especially those who struggle with literacy issues. Fiction takes licenses which can make it even more entertaining and accessible to readers who struggle with literacy. The middle school and high school age young people who I work with usually respond best to my fiction recommendations. However, I really enjoyed Dwayne Betts’ book. It is a story of redemption and does not come across as preachy or after-school special like. Here’s a short description:

At the age of sixteen, R. Dwayne Betts-a good student from a lower- middle-class family-carjacked a man with a friend. He had never held a gun before, but within a matter of minutes he had committed six felonies. In Virginia, carjacking is a “certifiable” offense, meaning that Betts would be treated as an adult under state law. A bright young kid, he served his nine-year sentence as part of the adult population in some of the worst prisons in the state.

A Question of Freedom chronicles Betts’s years in prison, reflecting back on his crime and looking ahead to how his experiences and the books he discovered while incarcerated would define him. Utterly alone, Betts confronts profound questions about violence, freedom, crime, race, and the justice system. Confined by cinder-block walls and barbed wire, he discovers the power of language through books, poetry, and his own pen. Above all, A Question of Freedom is about a quest for identity-one that guarantees Betts’s survival in a hostile environment and that incorporates an understanding of how his own past led to the moment of his crime.

I could have gone on but I felt that this list was a good beginning. All of the books that I mentioned above have male protagonists because I thought that the young man who I was recommending the books for would find these characters appealing and perhaps relatable.

Because I have spent over 15 years specifically working with young women in gender-specific programs, I am going to suggest a book titled “Upstate (2005)” by Kalisha Buckhanon. I ran a book group for young women of color in their teens a couple of years ago where we read “Upstate.” The young women LOVED this book. Here is review from Booklist:

With e-mail being used for everything from business memos and meeting reminders to tender love notes, the epistolary novel– with a history stretching from the days of Samuel Richardson and Choderlos de Laclos’ Liaisons Dangereuses to, more recently, Helene Hanff’s 84 Charing Cross Road and Alice Walker’s Color Purple– seems to be burgeoning again. Buckhanon’s foray in the format presents a decade of correspondence between Antonio, initially a teen arrested for murder, and his sweetheart, Natasha. Both from tiny, dark apartments in Harlem, they are passionately in love and lust but destined to walk very different roads. Eschewing Walker’s more dialectal language, Buckhanon opts for writing that is best called “lite,” suggesting New York City black speech but not so authentically as to compromise mainstream audience potential. Those aware of how unlikely success is for young women in Harlem and felons in and out of lockup might take issue with Buckhanon’s somewhat sanitized depiction. Others may eagerly anticipate a TV adaptation of it. — Whitney Scott

If you are an educator or youth worker, I have a terrific curriculum to teach “Upstate” to young women for those who might be interested. Please feel free to e-mail me and I can share it with you.

By the way, I would love to hear others’ suggestions of good YA books about incarceration. So feel free to let me know your ideas.

Happy reading!