Do We Really Want More Policing in Communities of Color?

I work with members of a block club on the West side of Chicago. This group of mostly elderly black women is courageous, committed and a lot of fun to be around. Over the years, the “ladies” as I like to call them have consistently advocated for a more responsive police presence in their community.

Anyone who has ever organized in a low-income community of color has confronted this dilemma – how to address the reality of police violence and harassment while responding to community members’ demands for safety. I write often about the police on this blog. I believe that as the most visible gatekeepers of state power, I can’t write enough about the police.

On Friday, the Chicago Tribune reported on an ACLU suit alleging that the police respond more slowly to calls from minority neighborhoods than white ones:

On Thursday, the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois filed a civil rights lawsuit against the city that alleged Chicago’s deployment of police officers results in slower response times to 911 calls in primarily black and Hispanic neighborhoods compared with service in largely white communities.

“Because of experiences such as this, many of our neighbors simply will not call the police,” Reid, who is black, told reporters at a news conference at the ACLU’s downtown offices.

The Central Austin Neighborhood Association in Chicago’s crime-plagued West Side also joined the lawsuit filed in Cook County Circuit Court. Reid is its president.

The suit is based on recent news reports that found police districts that cover minority neighborhoods had disproportionately fewer officers than those covering white neighborhoods as measured by response times to emergency calls and rates of serious violent crime.

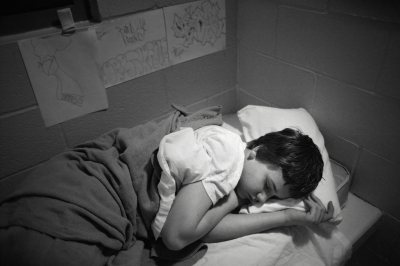

People who live in communities that are plagued with crime and violence understandably want to feel safe. They have that right. However, I have to wonder if it is a bad thing that community members living in Austin are not calling the police. For me, the question that we have to ask is:”Does an increased police presence in a community necessarily translate to more ‘safety’?” Instead of blanketing Austin with more police officers, can we instead find a way to provide jobs to all of the young men who are chronically unemployed? This is the best prescription for crime and violence.

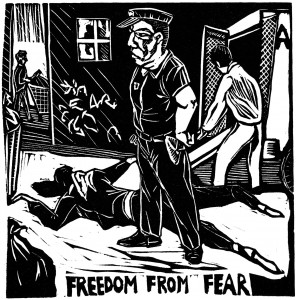

Part of my work involves imagining (and then implementing) alternative ways of addressing community safety that do not rely on policing. The reality is that for many, many people, the police do not actually engender a sense of safety. Instead they can be the purveyors of violence. I read a good blog post about this very issue last week in Feministing.

“Folks who have grown up with the police serving and protecting them understandably think the police work for them. Folks who’ve grown up being harassed by the police – who’ve seen their family members pulled over for no reason, arrested for being in public space, or totally ignored or even charged when they were a victim of a crime – have a different image. When the cops work for you, it seems like a pretty good idea to trust them to serve and protect. When you’ve been a target of the police, you tend to see a different picture.”

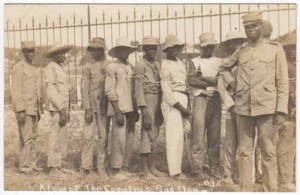

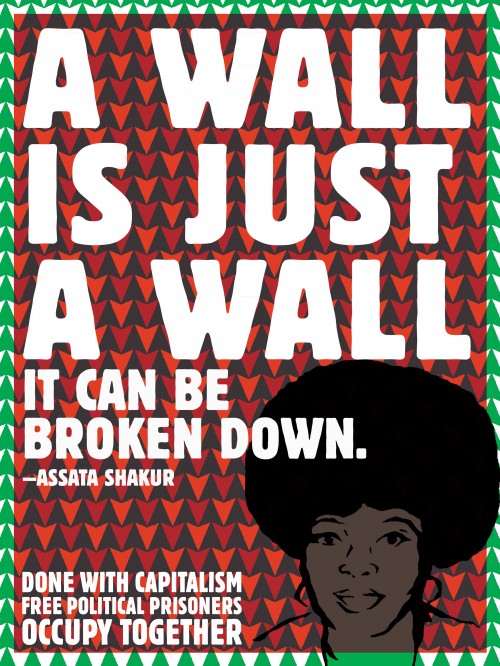

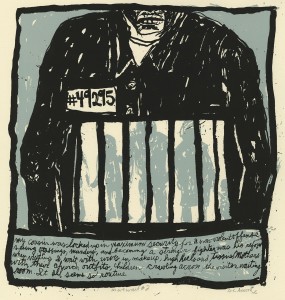

Communities of color have always had a complicated relationship to law enforcement (at best). For example, Public Enemy’s 911 is a Joke is a commentary on the fact that emergency services neglect people who live in black and brown communities. While NWA’s F-the Police points to the hostility that young people of color feel towards their police aggressors. Most recently prominent figures like Cornel West have been publicly denouncing and protesting the NYPD’s Stop and Frisk Policy which is described as:

“a method the police department enforces in an effort to reduce crime in the city. Under the policy, officers may stop individuals who are suspected of criminal activity without clear cause. Once stopped, officers may ask for identification and conduct “pat downs” or “frisks” in which they search for illegal drugs or weapons.”

Stop and Frisk is a gross violation of our rights as citizens and seems designed to increase people of color’s mistrust of and anger towards the police. Next Saturday, a group of us are coming together to participate in a participatory action research project called Chain Reaction: Alternatives to Calling the Police. I will periodically update our progress on this project. I hope that it will provide us with some workable alternatives to relying on the police to address youth misbehavior. Stay tuned!