Next Time I’m Asked About Black People and Violence…

I am just going to play this clip and shut up…

I am just going to play this clip and shut up…

I have to admit to being a Gwendolyn Brooks groupie. I was blessed to see her read some of her work first in 1992 in NYC and then again in 1996 after I had moved to Chicago. I have too many “favorites” of her poems. If I had to choose my all-time favorite though, it might be this one: “The Boy Died in My Alley.” I love it because it does a beautiful job underscoring the responsibility that we each have as human beings to care for all young people but most especially the ones most marginalized in our culture.

The red floor of my alley

is a special speech to me. – Brooks

While some people are only now waking up to the connections between the military and the PIC, this has been a trend for decades.

Julilly Kohler-Hausmann has written a terrific chapter titled “Militarizing the Police: Officer Jon Burge, Torture, and War in the ‘Urban Jungle’” which appears in Stephen Hartnett’s edited volume Challenging the Prison Industrial Complex.

Hausmann suggests that: “Americans, as domestic political unrest and the war in the jungles of Vietnam intensified during the late 1960s, increasingly referred to ‘urban jungles’ to organize their comments about the homefront (p.48).”

Furthermore, she adds important information to our understanding of the history of the militarization of law enforcement:

“Urban areas had long been constructed as foreign, racialized spaces; once they were in open revolt, their struggles with state authority were easily interpreted with the same rhetorical devices used for insurgent populations abroad. Thus, it is not surprising that over time, more and more voices called for the state to use the same tools and techniques employed overseas to subdue allegedly dangerous spaces. And so, by the mid-to-late 1960s, domestic law enforcement agencies had begun to interpret the conditions in inner cities as wars and had begun to turn for answers to military training, technology, and terminology (p. 48).”

A couple of weeks ago, I raised the point that some rappers in the 1980s and 1990s were likening their communities to “war zones” and the police to “an occupying force.” What I did not consider in that analysis is that this characterization pre-dated them. Hausmann quotes Inspector Daryl Gates of the LAPD as saying that “the streets of America had become foreign territory” during the 1965 Watts rebellions. It turns out that modern rappers were responding to the conditions in their communities engendered by a war that had been declared decades earlier by the state. Around the same time that Inspector Gates was making his comments about Watts, black nationalists and other activists were describing themselves as inhabiting “colonies” within the United States and being “occupied people.” Here is a quote cited by Hausmann from Black Panther David Hilliard in his autobiography illustrating this concept:

“we’re a colony, a people with a distinct culture who are used for cheap labor. The only difference between us, and, say, Algeria, is that we are inside the mother country. And the police have the same relation to us that the American Army does to Vietnam: they are a force of occupation which will stop at nothing to keep us under control.”

So interestingly, we had the representatives of state power and their targets reinforcing each others’ message that the inner city was “foreign territory.” Ironically by reinforcing the message that the “ghetto” was a war zone (which reflected the truth of their daily experiences in these communities), marginalized people were unintentionally watering the seeds of their own destruction and further oppression.

1968 brought a new opportunity for urban police forces to purchase new equipment and technologies thanks to funding from the passage of the Safe Streets Act. They also had license earned by the social anxiety and fear engendered by Vietnam and domestic urban rebellions to turn these new products on the marginalized population of the inner cities across America.

Jon Burge served in Vietnam in the late 1960s as a military police officer and was responsible for among other things transporting and guarding prisoners of war. Hausmann suggests that he would have observed some of the techniques employed by military intelligence officers who were interrogating prisoners. One of the tools that these intelligence officers used was a “field phone” as an instrument of torture. Hausmann writes:

“Many also admitted that it was common for military intelligence officers to rig wires from hand-cranked field telephones to shock prisoners, ostensibly to extract confessions and information. But the use of field phones in torture was not limited to Vietnam, as the first reports of the device actually surfaced stateside, where it was allegedly assembled in the early 1960s by a doctor at the Tucker Prison Farm in Arkansas. Knowledge of this device, often called the “Tucker telephone,” migrated to Vietnam and references to its use have subsequently been reported all over the world (p.57).”

What is striking about this description of the field telephone is that it illustrates how technologies easily migrated between the U.S. to the war zone and back again.

Burge joined the Chicago Police Department in 1970 and was promoted a couple of years later to detective in Area 2. Hausmann tells us that “the first reports of abuse surfaced shortly after Burge joined the force; the Tucker telephone reappeared in 1973 when Burge used it to torture Anthony Holmes during an interrogation (p.57).”

Between 1972 and 1991, Jon Burge tortured or supervised the torture of more than 100 people (all except one were African American). The methods of torture were diverse, systematic and brutal; additionally the torture which was perpetrated by a group of white detectives who called themselves the “A-team” was always verbally laced with racial slurs:

“He and the detectives under him used a variety of techniques, including beatings, Russian roulette, shocking, and mock executions to coerce confessions from crime suspects; these techniques were intended to inflict high levels of pain or fear without leaving any physical evidence of violence; most of these forms of torture would be familiar to people knowledgeable about the unsanctioned but pervasive interrogation procedures employed by U.S. forces in Vietnam. On other occasions, victims were handcuffed to hot radiators, forced to strip, and repeatedly beaten on the genitals. Officers suffocated some detainees by placing a large bag or typewriter cover over their heads; Burge and his colleagues also shocked victims on the scrotum, penis, anus, fingers, or ears with a cattle prod or the field phone (p.57-58).”

You should all read Hausmann’s entire chapter for more information on the Chicago Police Torture cases and their connection to the militarization of police forces. Additionally, for more information about the cases, visit the site for the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, a terrific project that I am proud to be associated with.

Update: Thanks to reader Eric for flagging this story and sending it to me. It looks like just today the deaths of two black men in Area 2’s police station have been ruled “suicides.” Attorneys and supporters of these men’s families are invoking Burge and raising suspicions as to what really happened.

Those who know me well have heard me lament about academic disciplines enough that it has become tedious. I know.

I am particularly morose about my own discipline of sociology. Sociology and I had a whirlwind courtship and I fell passionately in love with him. We got married and much to my dismay I found out that he wasn’t what I thought he was when we first met. We tried marriage counseling but ultimately we had to divorce. Over the past few years, we’ve been rekindling our friendship on new terms.

When I went to college, I first majored in economics. It became clear to me early on that this wasn’t a good fit. I took a sociology course and I was hooked. I was introduced to sociology by some particularly terrific professors who made the subject come alive for me. Sociology, the study of society, was sexy and appealing. I didn’t even have to try to think “like a sociologist.” It came naturally to me. Our relationship made sense and helped me make sense of myself and the world around me.I decided to get serious with sociology after a couple of years together. I went to work and saw him on the side at night. Sociology convinced me that I would become the next Jonathan Kozol. That dream got me through a Masters degree. I was sure that I had found a way to marry my passion for social theory with my driving need for social activism and organizing. I just knew that engaged and applied scholarship was the way for me.

Sociology convinced me to marry him. It was time to get serious and commit to a long-term relationship. I entered a Ph.D. program and it took less than six months for our relationship to begin to show cracks. I felt really lonely with this new version of sociology. When we left New York, sociology changed. Suddenly he didn’t value applied work. He became obsessed with words like “scientific inquiry,” “validity,” “reliability,” and “objectivity.” It’s like we weren’t even speaking the same language anymore. Sometimes, when he wanted to piss me off, he would use words like “hegemony.” That was a fighting word…

He found some new friends with whom I had little in common. Those friends didn’t look like me or sound like me. In fact, those friends seemed to have open contempt for me. My interests in race, gender, and social activism made me alien to sociology’s new friends.

Soon he told me to avoid telling others that I wanted my research to contribute to changing the word. He said that no one wanted to hear about that and that it would in fact alienate me even more from our new friends. When I told him that I wanted to hang out with some of the people who I was doing research with, he told me that this was frowned upon. When I told him that I wanted to teach in community colleges, he told me that my aspirations were too low. “You really should be aiming to teach in a tier-one “research” institution,” he would say. “All of the “best” people hang out there.”

I started writing and sending my work out. He would admonish me to publish in the journals that are most respected by the discipline. Those were ones that were read by perhaps 10 other people (perhaps only 5 if folks were being honest). When I would show him some of my writing, he would tell me that it was “good journalism” but not actually sociology. I didn’t use the word “hegemony” enough.

Slowly, I began to lose my passion for him. I started to resent him. I talked badly about him behind his back and I started cheating on him. I became promiscuous. I would write articles and send them to education journals, I would publish pieces in policy publications, and I even submitted work to be published in an anthology that I knew would not be read by his friends.

He tried to keep me in line but I started openly flaunting my disdain for him by telling others that he was inauthentic and a liar. We had a trial separation and it lasted several years. Eventually we reconciled for a while as I made my way through the morass: despondent, bitter, and disillusioned. We had our Crystal anniversary. I didn’t want to celebrate the milestone. I didn’t tell anyone that it was our anniversary. After years of trying to make it work, we finally divorced. We had both tried our best. We didn’t leave on friendly terms. All I had to show for our time together was a piece of paper unframed and a mountain of debt.

Then a funny thing happened. From a distance, I started to remember what I had once loved about him. I also noticed that I had listened to our friends more than to my own instincts. Those friends were the ones telling me that sociology didn’t like to eat theory with practice. Those friends were the ones who kept insisting that I needed to use words that no one in my family understood in order to be a good partner to sociology. I realized that our friends had become the interlocutors for sociology. Sociology’s own voice had become muffled and I had stopped listening closely to what he was saying to me.

Sociology and I are no longer in love but I find that some of the original qualities that I liked about him are still there. I decided to rekindle our friendship and that’s where we are today. We are old friends who still argue sometimes but basically like and respect each other.

You are no doubt wondering what the point of this post is… Well, I wanted to say something about how difficult it is to marry theory and practice in academia. When I see examples of people who do this well, I am always in awe. I have some friends who seem to have gotten the hang of doing this. They are stellar academics who remain firmly committed to ensuring that their work contributes to social change and justice. My own experience illustrates how hard this is. I wanted to feature one such person here today because I have so much respect for what she does.

Rachel Marie-Crane Williams is a talented artist, a great teacher and an engaged scholar. She and I have collaborated on a zine project and continue to find ways to work together. In fact, Rachel is currently creating a police violence zine that will form the basis of a new curriculum that I am developing.She uses her skills as a teacher and artist to work inside prisons and she also provides a template for others to do the same. She has written engagingly about “doing qualitative research in prisons and turning the data into graphic essays.” She is also developing a series of stories about working in prisons. I want everyone to see her amazing work. It is inspiring to me and I think that it will be to you too. It is important in this life to find touchstones who can help light the path for us to imagine what’s possible. Rachel has become just such a touchstone for me. You can see some of her work here.

As 2011 comes to a close, I want to offer a few words of gratitude to the regular readers of this blog. When I began writing here in July 2010, I had no idea what I would be getting myself into. I had no expectations that anyone beyond my immediate family (perhaps) would care to read my random musings about the prison industrial complex. In the last year and a half, I have made new friends through this endeavor and I have learned so much from total strangers. It is astonishing, really.

I always appreciate your e-mails (of support and also those that take issue with me). I have also had the rare privilege of starting new pen pal relationships with current and formerly incarcerated people because of this blog. I so appreciate your ideas and most importantly your desire to use your stories to teach and to transform.

It has been an extremely busy and sometimes trying year for me. I have a more than full-time job running a grassroots organization, I have been teaching some college-level courses, and I am involved in countless other activities. In between, I have been trying to remain a good friend, sister, auntie, daughter, godmother, and partner. We all need time to refuel and recharge so I am going to take a few days off during the holiday season. I will be back here regularly blogging in the New Year and I hope to continue our conversations (even when they are one-sided).

Before I sign off for the next few days though, I wanted to relay a story about a young man who I have been working with for the past few months. He has been struggling greatly since his release from prison in March of this year. He is ill-equipped for “life on the outside” as he likes to say. He is easily angered and raises his voice to make mundane points. Any suggestion is perceived as a criticism and a slight. His favorite word to use is “respect” and yet he has a difficult time showing any for others. I am not telling tales out of school since everything that I am writing about him, I have also expressed directly to him (more than once).

Just last month, he told me that he has been reading my blog regularly for the past three months. I never tell the young people who I work with that I blog unless there is a story involving them that I want permission to share. Frankly, I was surprised when he told me this because one of the issues that we are tackling is his unwillingness to follow-through. So the fact that he makes time to regularly read anything is a victory to me.

For the past couple of weeks, I have been pressing him to write something that I can post on the blog. I think that it would be a good way for him to express himself and perhaps even get some feedback/encouragement. He has resisted my entreaties so far but I am persistent. I believe that he has it within him to be a powerful storyteller. He is brilliant and verbally gifted. So in lieu of writing something, I asked him what he might want to share with readers of this blog. What he shared was simple and yet so profound: “Tell them that I am a human being,” he said. I won’t analyze what he meant by this. I will leave it up to you to imagine. However, I hope that he will take me up on my offer to give him space to write on this blog in the new year. I hope that he will choose to expound on the words that he wanted to share with you as readers.

One of the ways that this young man and I connect is by exchanging some of our favorite poems. The selections that he has encouraged me to read have had a real impact on my thinking and on my life. When I saw him yesterday, he gave me a new poem. He told me that it does the best job of expressing his own feelings about prison. “If I were a poet, this is a poem I would write,” he told me. Then he asked that I share the poem with you. Happy Holidays and may 2012 bring you peace, health, and inspiration!

Prison Letter

by M.A. Jones

1982, Arizona State Prison – PerryvilleYou ask what it’s like here

but there are no words for it.

I answer difficult, painful, that men

die hearing their own voices. That answer

isn’t right though and I tell you now

that prison is a room

where a man waits with his nerves

drawn tight as barbed wire, an afternoon

that continues for months, that rises

around his legs like water

until the man is insane

and thinks the afternoon is a lake:

blue water, whitecaps, an island

where he lies under pale sunlight, one

red gardenia growing from his hand —But that’s not right either. There are no

flowers in these cells, no water

and I hold nothing in my hands

but fear, what lives

in the absence of light, emptying

from my body to fill the large darkness

rising like water up my legs:It rises and there are no words for it

though I look for them, and turn

on light and watch it

fall like an open yellow shirt

over black water, the light holding

against the dark for just

an instant: against what trembles

in my throat, a particular fear

a word I have no words for.

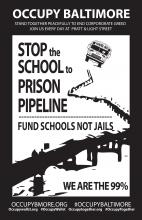

I have been thinking a lot about the ways in which the Occupy Movement is adapting and reconstituting itself on a daily basis. This is a good thing. I’d like to suggest that it is way past time that we start occupying the public schools in low-income communities across the country. What is happening inside these buildings is a national disgrace. Just yesterday, I read a disturbing article about the fact that the juvenile justice system in Meridian, Mississippi is now under federal investigation. Many of the most egregious incidents under investigation actually originate from local public schools:

I have been thinking a lot about the ways in which the Occupy Movement is adapting and reconstituting itself on a daily basis. This is a good thing. I’d like to suggest that it is way past time that we start occupying the public schools in low-income communities across the country. What is happening inside these buildings is a national disgrace. Just yesterday, I read a disturbing article about the fact that the juvenile justice system in Meridian, Mississippi is now under federal investigation. Many of the most egregious incidents under investigation actually originate from local public schools:

An 8-year-old student in Meridian who had been paddled for talking in class was hauled away in handcuffs when he wouldn’t stop crying.

A middle school student spent three days behind bars at the Lauderdale County Juvenile Detention Center after he wore the wrong socks.

A high school student spent five days behind bars after she was tardy

Unsurprisingly, each of these incidents involved African-American students. When I give talks about the issue of the school-to-prison pipeline, I sometimes encounter resistance from audiences who want to see such examples as outliers. In fact, in the 21st century, harsh school disciplinary policies and zero tolerance are actually the norm in most urban public schools.

Instead of looking for ways to disrupt the symbiotic relationship between schools and law enforcement, politicians are looking for ways to cement those ties. Here in Illinois, an effort is underway to violate student privacy by mandating the exchange of information between law enforcement, schools and juvenile justice advocates:

“Right now, in Illinois, while information-sharing agreements between schools and police are suggested in the state’s school code, they are not required. Schools that have them usually do not spell out how communication should happen, nor how quickly, nor do they keep any sort of data on student police reports and arrests. And police aren’t required to communicate to school officials about ongoing investigations at all…”

I am completely fine with this way of doing business. But apparently some in the state are looking to change these reporting requirements. Mundelein Police Chief Ray Rose offered his rationale for increasing the exchange of information between schools and law enforcement:

“Years ago we used to talk about schools being the safe place. That’s questionable now,” Rose said. Because specific information sharing about students isn’t required, “We don’t know what they’ve been involved in.”

The assertion that it is “questionable” that schools are “the safe place” is preposterous. Schools ARE in fact still the safest places for most young people to spend their days. They always have been and still are. Research backs up this claim. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, incidence of violent crime in schools, already low, was halved between 1993 and 2008. Schools are safer places for most young people than their homes are. No, what law enforcement wants to do is to extend its reach even further into our schools. This is evidenced by another effort taking place between Chicago Police and Chicago Public Schools to launch a school-based CompStat pilot program for high schools:

“CompStat involves weekly crime control strategy meetings during which commanders share and discuss crime incidents, patterns and trends with command staff. The meetings focus on the statistical analysis of crime, where it occurs, how often and by whom, evaluate that and hold commanders accountable for the decisions they have made and the impact they have had on crime in their districts.

School-based CompStat will be unique from CPD CompStat, in part, because “in-school” and school level infraction and incident data will be reviewed in addition to neighborhood incidents. They will be viewed in relation to the violence that occurs around the school and in the surrounding community, giving educators and the police department a more complete picture.“

This increased surveillance within and outside of our school-buildings is being billed by Mayor Rahm Emmanuel as helping “to create a culture of accountability so we can end crime near our schools and make sure our students can focus on their studies, not their safety.” You know what would really ensure that students can focus on their studies in Chicago, ending the practice of “teaching to the test,” fully funding comprehensive enrichment programs, insisting that our best and strongest teachers work on our most challenging schools… I can go on. The focus on making law enforcement the end all and be all of ensuring student “safety” is a deeply flawed approach.

In light of the recently-released study suggesting that nearly a third of young people have been arrested by age 23, perhaps we need to take a step back and reassess our reliance on law enforcement to solve problems that were previously handled at the community level. Time for our communities to occupy our public schools in order to wrest control back from the criminal legal system!

Note: My old neighbor Lori Berenson has arrived in New York for the first time since 1995. Earlier this year, I wrote about her case here. Below is that post:

I have never written about this before. I am prompted to do so today because of a New York Times Magazine Feature Story that appeared over the weekend.

I was born and mostly raised in New York City. Growing up, I lived in an apartment complex in mid-town. My neighbor during those years was Lori Berenson.

Lori and I are two years apart. She is older than me. We lived on the same floor in a 8 story duplex apartment complex. This is a building where you got to know your neighbors. Lori’s family still lives in that apartment complex and so does part of my family. So when I go back to NYC to visit, I still stay in the apartment that I grew up in.

Lori and I had a cordial relationship. We were not close friends. She went to public school and I went to private school. When you are a kid, a two year age difference is a big gap. We traveled in different circles that did not overlap. Yet when we ran into each other in the laundry room, in the elevator, at the playground or at the supermarket, we would engage in light banter and chit chat. We were never close.

Lori and I were very similar in temperment. We both liked to keep our own company and did not particularly share our inner-most thoughts with others. We were both serious young people. She was socially conscious even though her family was not particularly political. I too was a young social activist. In retrospect, I think that we would have had much in common to discuss.

Lori left for college a year before I did and I would see her from time to time during the holidays when we were both back home. Lori became interested in Latin America. I was taken with the Caribbean. She traveled to El Salvador and was fascinated with radical nuns. I went to Cuba and was infatuated with Assata Shakur. By the time Lori was arrested in Peru in 1995 and sentenced to life in prison, I had moved to Chicago. I didn’t learn about her arrest until several months later.

What did I do once I learned about Lori’s arrest and conviction? I am sad to say… Nothing. When I would travel back to New York, I never stopped by to check on her family, to ask for news of Lori. I was silent about the situation and so were most of our other neighbors. I think that people were shocked by what had happened and I do not think that anyone knew how to react. I certainly did not.

After the first year of Lori’s imprisonment, I finally started to do things like signing petitions asking for clemency and making phone calls to elected officials asking for them to intervene in her case. But still, I did not directly reach out to her family to offer my support and to ask how I could help. I could have done so at any point and I just did not. I felt guilty about it but I didn’t know how to broach the subject when I would run into her parents. I feared that they must be exhausted from the sad looks and the probing questions. Instead, I acted like nothing was amiss. I acted as I always had with them. Saying hello in the elevators and making small talk.

Over the years though, I became obsessed with following any information on Lori’s condition. I looked for ways to support efforts that were set up to free her from prison. To this day, over 15 years later, I have not yet talked to her parents about Lori’s situation. It feels too late now. That time has passed. I built a wall between the personal and the political. I felt comfortable swimming in the river of the political. This has always been the case for me. I wonder how many others of my neighbors did the same. We have never talked about it. Where Lori Berenson was concerned, the residents of East Midtown Plaza adopted a generalized posture of silence.

Lori is on parole in Peru now. “Free” after 15 years in prison. She is unable to leave the country until 2015. I can’t even imagine what she has endured over all of her years of imprisonment. Now she faces a new challenge: social ostracism in a country that despises her. How much can a person endure? Some part of that answer can be found in the last few paragraphs of the Times story about Lori. I think that it captures the essence of the woman. I encourage those interested to read the entire article. It is long but it needs to be.

In the 15 years Berenson spent in prison, her peers have moved from early adulthood into middle age. “The world has changed,” she told me in August. “Internet, giant malls.” Technologically, she’s catching up, and has grown comfortable using e-mail and Skype. But at 41, she is still grappling with the fallout of youthful choices that have ended badly: her vocation; her marriage; her love of Latin America. The passion that fueled her move there seems to have left a kind of void, and beyond the need to support herself and her son, her future remains a blank.

Of course, Berenson’s future won’t really be her own until her parole ends; for now, she is raising Salvador alone in Peru, with limited options. If she ever feels despair or defeat at these conditions, she wouldn’t show it — not at 26, with a life sentence in front of her, and not now. Her capacity to absorb fear and discomfort is partly what has saved her — and also, most likely, what got her into trouble in the first place. But this is speculation; Berenson resists such storytelling, leaving the rest of us to our own devices in trying to unlock the mystery of her biography. What she can’t elude is our desire to do so: a notoriety she has sustained, uncomfortably, for most of her adulthood. “I am always conscious,” she said, “of who I am.”

Click here to watch video of Lori speaking for herself. Lori Berenson was a political prisoner and also my neighbor…

I spent my afternoon giving pedicures to incarcerated girls. I am not a Christian but I remember something about Jesus washing the feet of his disciples on the night that he was betrayed by Judas. Supposedly this act was meant to convey his humility and his abiding love for his disciples. There is something moving about the act of touching feet. Particularly if those feet belong to people who you know have experienced profound suffering.

As I massaged the feet of girl after girl, we would talk. Mostly, we spoke about how long they had been incarcerated and about when they would be released. Some girls asked whether I was a professional nail technician and when I said that I was just a volunteer, their eyes would widen and they would thank me for being there. “God bless you,” a young woman said. “No one has ever done something so nice for me.”

That is a travesty. If the nicest thing that you’ve ever had done to you in 17 years of living is a pedicure inside a prison, then your life must have been pretty awful. And that’s just it. As I listened to the young women talk about having been incarcerated for 7 months, 1 year, 24 months, I felt a heaviness settle in my heart. Prison is no place for children. It is no place for anyone really.

The heaviness of my heart co-exists with the constant (if sometimes fleeting) hope that I also carry within me. I looked around the room where I was sitting and saw my friends and some strangers also painting nails. Most importantly, I listened as they spoke with care and love to the young women who were receiving manicures and pedicures from them. The older I get, the more convinced I am that nothing worthwhile can be done in isolation. I am thankful for the community of women who I am blessed to share space with on this planet. I don’t think that women only hold up half of the sky; I think that we carry at least 3/4 of it. Time and again, when I put out the call for support it is my sisters in struggle (friends and strangers) who answer. They give of their time, they contribute money, they donate items, they organize, they nurture… and basically they just SHOW UP. As I recover from organizing these two self-care events this weekend, this is what continues to inspire me and give me fuel for the next endeavor. My profound gratitude to everyone who helped make these two days wonderful.

People still laugh in jail… This seems a trite thing to say. However it never ceases to amaze me. I have been inside enough prisons and jails to last me a lifetime. I have always had the option to leave.

The saddest places on earth to visit are juvenile detention facilities and youth prisons. No matter how many painted murals are on the walls, no matter how many colorful works of art hang in the classrooms, they are awful places to be. When you think of the fact that young people under the age of 18 reside there, how can they be anything else?

Yet today I was reminded that people still smile in these places. I am thinking about this tonight after having spent a couple of hours at a self-care event at my local juvenile jail earlier in the day. I was speaking with a couple of the incarcerated girls and we were laughing together. I glanced over and another young woman sat stone-faced. No smile on her face.

I thought to myself: “That’s how I would be if I were locked in this place for God knows how long.” I wouldn’t be laughing. I would be sitting in a corner looking devastated. Yet for the majority of the girls today, there were smiles and there was banter. They are after all still children even if the world treats them like adults.

For a few hours this afternoon, volunteers (each an amazing woman in her own right) did yoga and aromatherapy with the girls. They offered intuitive readings and painted fingernails. They massaged the girls’ hands and spoke with them. And yes, we even laughed. Thank God for small miracles.

I am serving on the advisory board for an upcoming exhibition about the history of the Conservative Vice Lords in Chicago. This will be a community-based exhibition in North Lawndale and is being curated by former CVL members, other partners and the Jane Addams Hull House Museum. So I have been thinking a little about the concept of “gangs” and their connection to violence lately.

Yesterday, Davey D shared some new music videos addressing current social issues. One of these is by Lupe Fiasco titled “Double Burger with Cheese.”

Davey D had this to say about Lupe’s new video:

His newest offering is to a song called Double Burger w/ Cheese where he goes in the power of images and how they may have impacted several generations of Black Youth.. The video starts off by showing footage from the 1965 Watts Riots and then juxtaposes it with an array of videos and images from movies in the early to mid 90s that focus both on South Central LA and the crack era..

We see footage from everything like; Juice, Menace II Society, Boyz N The Hood, New Jersey Drive, Poetic Justice, Dead Presidents, South Central, Sugar Hill, New Jack City, Paid In Full, & Colors. Although many of the movies shown have strong anti-gang messages, many of us have come to romanticize and glorify the gang drama and trauma shown in them..

I want to pick up on Davey D’s last point because I think that it is a particularly interesting one. If it is true that some people of color have internalized and romanticize gang drama and trauma, what impact does this have in our communities? Is the argument that these images make young people of color more prone to turn to violence themselves? Do the images have a desensitizing effect on those who watch them?

I actually think that these images have more impact on the dominant culture than on marginalized young people. Robin D. G. Kelley (2000) has written that:

“The mainstream media have [sic] employed metaphors of war and occupation to describe America’s inner cities. The recasting of poor urban Black communities as war zones was brought to us on NBC Nightly News, Dan Rather’s special report “48 Hours: On Gang Street,” Hollywood films like Colors and Boyz N the Hood, and a massive media blitz that has been indispensable in creating and criminalizing the so-called underclass (p.24).”

In other words, according to Kelley, the very images referenced in Lupe Fiasco’s video, were critical to creating and criminalizing the underclass in the American public imagination. These images help to legitimize the militarization of police forces and to justify tough-on-crime policies. Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman correctly points to the futility and vicious cycle of increased police repression in marginalized communities: “The sole effect of extemporary police actions is to render the need of further police actions yet more pressing: police actions, so to speak, excel in reproducing their own necessity.” A far better approach would be to address the root causes of violence in marginalized communities. Yet this gets short-shrift.

When I discuss gangs with my students, I often screen a documentary titled “Crips and Bloods: Made in America.” In particular, I like to show a clip that makes explicit the connection between economic disinvestment and the rise of gangs.

Commenting on the street violence in South Central LA in the film, Tom Hayden says: “It’s been defined as a crime problem and a gang problem, but it’s really an issue of no work and dysfunctional schools.” This is basically where I come down too. However, I know that others would offer their own ideas about the root causes of gang culture. If you have the chance, I highly recommend watching the entire documentary.