Laura Scott, Female Prisoner, #21270 Part 4

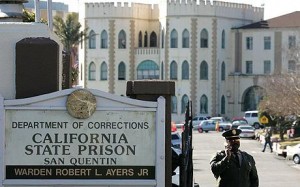

In California as in the rest of the country, little to no attention was paid to women prisoners in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Their numbers were very small relative to male prisoners. In 1904, a year before Laura Scott first entered San Quentin Prison, there were 1,451 men and 27 women incarcerated there (source: First Biennial Report of the State Board of Charities and Corrections, 1903-1904, p. 11).

After a highly publicized trial, Griffith J Griffith was convicted of shooting and wounding his wife and served two years in San Quentin Prison from 1904 to 1906. Before he was imprisoned, he had been very successful as a California business man and philanthropist. He made his fortune in the mining business. Throughout his trial, he consistently maintained that the incident with his wife had been an accident. As soon as Griffith was released from prison in December 1906, he began working on an expose of the conditions there. His account of his time at San Quentin is published in a book by the Prison Reform League (that I have referenced on the blog before) titled “Crime and Criminals.” Everyone with an interest in the early history of prisons in the U.S. should read his account of his time behind bars.

After a highly publicized trial, Griffith J Griffith was convicted of shooting and wounding his wife and served two years in San Quentin Prison from 1904 to 1906. Before he was imprisoned, he had been very successful as a California business man and philanthropist. He made his fortune in the mining business. Throughout his trial, he consistently maintained that the incident with his wife had been an accident. As soon as Griffith was released from prison in December 1906, he began working on an expose of the conditions there. His account of his time at San Quentin is published in a book by the Prison Reform League (that I have referenced on the blog before) titled “Crime and Criminals.” Everyone with an interest in the early history of prisons in the U.S. should read his account of his time behind bars.

Griffith also offered an expose of the terrible conditions for women at San Quentin that relied on the written account of an unnamed female prisoner who had spent several years incarcerated there. This account was corroborated by several other prisoners before it was published in Crime and Criminals. It is one of the only available first-hand testimonials of life inside San Quentin Prison for women at the turn of the 20th century.

Female prisoners at San Quentin were supplied with only the bare minimum of clothing and other items:

The state supplies each female prisoner every six months with six yards of white cotton, six yards of tennis flannel, and two pairs of hose. She is given also two blue denim dresses and one heavy blue flannel dress, called a “reception dress”. But it does not supply any underwear, corsets, underskirts, garters, hats, bonnets, coats or overshoes, and the sufferings of those who enter without such supplies and have no money to buy them are extreme. For there is no heat in the cells, and the thick walls, when thoroughly wetted and chilled, remain so all winter. ” It would have been amusing, were it not so pathetic, to see the straits to which the women were reduced to find something that would answer for underclothes, and they picked up from the sewing-room floor scraps of cotton flannel and, by great ingenuity and much labor, made garments. These garments, being most bulky, were refused by the laundry, as they broke the wringer.” In one of such garments the writer counted two hundred and forty pieces. The further comment is made that, although the state is supposed to issue the supplies previously mentioned every six months, they are habitually held back. If, therefore, for example, a woman’s supplies are due in April and she is to be released in May, she will be told that the supplies have not arrived, and will leave the prison without getting them.

What kind of work did the women at San Quentin Prison do?

From eighty to a hundred suits of underwear have to be made each week for the use of the men, but this, like the other work, is divided up. One woman acts as cook and there is a diningroom girl, whose duties are entirely below stairs. Nothing is taught that can be of the lightest use to the prisoner after her discharge, the accomplishments to be learned being cigarette smoking — each woman receiving every Monday afternoon her sack of tobacco and package of papers — and other vices. As to which the writer remarks : ” Nearly every woman there has voiced the sentiment, not once but many times : ‘I shall be a thousand times worse a girl when I leave this living hell than I ever dreamed I could be.’ And it is true, for the viler, lower traits are so encouraged, and whatever better impulses one possesses are so smothered and killed, that the entire nature is changed for the worse. This is no idle statement, for we all know that constant fear breeds hate, and from hate spring all the baser passions.”

Interestingly this account about life at San Quentin at the turn of the century spans the years when Laura Scott would have been incarcerated at the prison. Given this reality, when Griffith’s unnamed source mentions that a two-time negress convict worked as the dressmaker of the prison, one might wonder if this could have been Laura Scott herself. Remember that her occupation was listed on prison and arrest records as dressmaker/seamstress. Many of the dates mentioned in the account range from 1906 to 1909. These would have years that overlap with Laura’s time as a prisoner at San Quentin.

The next installment of this story will focus on the purported racial dynamics between women prisoners as well as on how female prisoners were treated by staff (both male and female) at San Quentin. Stay tuned!