Upon her release from prison in June 1906, it is unlikely that Laura Scott would have been able to find gainful employment immediately. She was a convicted felon who had spent nearly a year behind bars in the notorious San Quentin. Given what we know today about the high rate of recidivism for people who have been incarcerated, it should be no surprise that Laura found herself in trouble with the law again a few months after she was discharged.

On February 17 1907, Laura Scott was arrested by detectives Glenn and Stevens, both of whom were also black and she was charged with petty larceny. She was accused of stealing an alarm clock from Ms. H.C. Russell. According to the L.A. Times: “It was the last of a series of petty thefts on her part during the past ninety days (2/21/1907).” She allegedly sold the clock for 25 cents at a local pawn shop. She was bound over to the Superior Court and jailed while awaiting her trial.

Laura’s trial took place on April 8th 1907. The L.A. Herald sets the scene:

“Yesterday department one was crowded when the Scott woman’s case was called. Many of those among the spectators had contributed their mite to help in defending her and all were anxious to testify as to her general good character up to the time when the alleged purloining of the clock occurred.”

Mrs. Russell was the chief prosecution witness and she told the court what happened:

“On the afternoon the clock was taken [February 16] I was ironing when Miss Scott came in and sat down and began to talk. We had considerable conversation there, and I kept right on with my ironing. At that time the clock was on a table near where Ms. Scott sat. […] When she went out I didn’t notice at first that the clock was gone, but a few moments after that I discovered that I had lost the clock.”

Throughout the trial, Laura Scott maintained that she was innocent of the charges against her. The L.A. Times described her as having a “sullen and serious countenance” throughout the proceedings. This was in stark contrast with the demeanor of another key witness against Laura: Lizzie Douglas. Lizzie was described as a mulatto “whose mouth curved in a wondrously humorous and expansive smile as she cakewalked to the witness stand (4/9/1907).”

In her account, on the morning of February 16th, she had gone over to her friend Mrs. Russell’s home to help with ironing. Mrs. Russell brought out an alarm clock and set it on the “ice chest.” As she testified on the witness stand, Lizzie would periodically break out into fits of laughter as she remembered the details of the incident. Laura Scott came into the Russell home on San Julien Street for a “pall of beer.” Lizzie added: “I had whiskey myself.” She continued:

“[Laura] began lounging about the room and leaned up against the ice box. She picked up a piece of paper and looked at it, she said Mrs. Russel’s phone bill didn’t read exactly like hers. Then Mrs. Raymond came in, and after a little while she asked what time it was. As soon as she said that, Laura Scott went out. Mrs. Russel told Mrs. Raymond to look at the clock. Mrs. Raymond said she didn’t see any clock. Mrs. Russel asked her if she was blind, and told her to look on the ice box. Mrs. Raymond said she did, but she didn’t see any clock. We all looked then, and the clock wasn’t there. Then Mrs. Russel sent her boy to tell Mrs. Scott to bring the clock home.”

Upon cross-examination, Lizzie Douglas was asked by Laura Scott’s attorney, Mr. Taylor: “But you didn’t see her take the clock?”

Lizzie: “No.”

Attorney Taylor: “As a matter of fact, you don’t know that she did steal it, do you?”

Lizzie: “It couldn’t a jumped down off of there and walked away.”

Attorney: “What time did the defendant leave the house on San Julian street?”

Lizzie: “How could I know that? The clock was gone, and there wasn’t no way to tell the time.”

Rosa Goldberg, who owned a pawn shop with her husband on First Street, was called to the stand by the Prosecution. The L.A. Times reported on her testimony:

“Where is your store,” asked Deputy District Attorney Blair.

“At First and Alameda streets.”

“In Los Angeles?” pursued the prosecutor.

“Of course,” returned the witness, with an air of pitying his ignorance.

When it was the defense’s turn, attorney Taylor representing Laura Scott, “asked the witness how she could identify that clock.” “Isn’t it just like thousands of others you can buy at jewelry stores for 75 cents?”

Mrs. Goldberg: “I never bought any at a jewelry store. I paid 25 cents for that one.”

“But how do you know that is the one?” persisted the attorney.

“That is the clock,” Mrs. Goldberg replied decidedly.

Attorney Taylor also tried to impeach the credibility of the detectives who arrested Laura Scott by claiming that they “tricked her into making admissions.” However officer Glen testified that it was Laura who had told them where they could recover the clock. He added that she offered to pay for it. It took two hours for the jury to come back with a guilty verdict against Laura. The L.A. Times described her disposition during the trial and her reaction to the verdict:

“Laura Scott showed little feeling when the verdict was announced, and not much at any other time during the trial except one. That was when her attorney, in his argument, spoke of her as Ada Scott. She whispered sharply to him across the table with every show of anger: ‘Laura Scott’. And to her friend Ada Stanley, she remarked, ‘The fool’.”

Because she had a prior conviction of larceny, the offense that she was convicted of became a felony. However, her friends who had packed the courtroom on April 8th, would “plead for a probation sentence instead of a penitentiary term (L.A. Herald, 4/9/1907).” There are no records of her being incarcerated at San Quentin in 1907 so this leads me to think that she was either sentenced to county jail or given probation. I am still investigating the sentence.

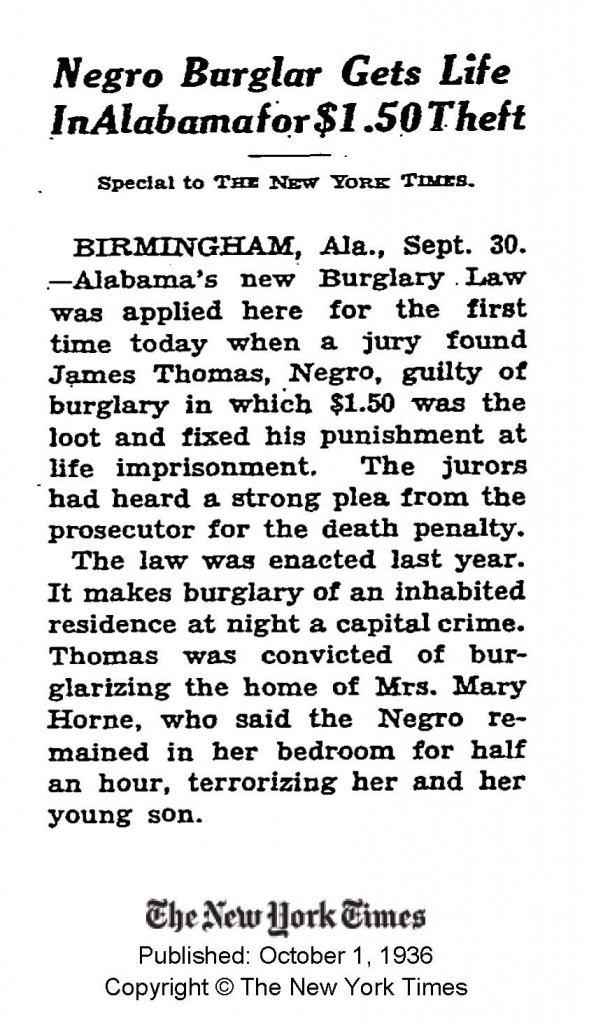

The L.A. Herald in reporting on this case pointed out that the trial “cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $200 to the county and probably nearly as much to the woman’s friends.” $200 in 1913 is the equivalent of $4,544.22 in 2011. This suggests that $200 in 1907 would easily be worth more than $5,000 today. It seems like a waste of valuable resources to have tried a woman for stealing an alarm clock worth 25 cents at a cost of about $10,000 (to the state and to the defendant). This example underscores the point that the American legal system has always been wasteful and irrational.