Why Assata Shakur Still Matters?

One of the reasons that I continue to believe in the potential of hip hop to educate and to help transform is because of cultural artifacts like Common’s “A Song for Assata.”

One of the young people who I have been mentoring for some years just discovered this song a few weeks ago. She reached out to me and wanted to discuss it.

“Ms. K, do you know about Assata Shakur?” she asked.

“Yes indeed I do know about her?” I answered

The young woman who I will call Brittany wanted to talk about Shakur’s escape from prison. “How did she get away?” she wanted to know. She also wondered if it was true that Assata was Tupac’s “aunt.” My answers to both questions respectively were “I don’t know” and “no, but she was his Godmother.”

For Christmas, I bought her a copy of Shakur’s autobiography “Assata.” Brittany e-mailed me in early January to say that she had read the autobiography and in her words thought it “was so so real.” She wondered why she hadn’t heard about Assata Shakur before and said that she was going to tell her social studies teacher about her discovery. According to Brittany, school “don’t teach us the important stuff.” Unfortunately, I have to agree.

This episode is another reminder to me that young black people will in fact read books (provided they are engaging and relevant to their experiences and interests). Brittany read over 250 pages in just a few days. This young woman is now scouring the internet for more information about Assata. I find myself smiling as I type this because I am always happy when our young people embrace reading and value literacy.

I have been thinking a lot lately about what Brittany finds so appealing in Shakur’s story. The theme of “escape” has traditionally been a potent one in African-American folklore. So perhaps her fascination in part stems from the fact that Shakur successfully “escaped” prison. Think of our general fascination with the Count of Monte Cristo for example if you doubt the power of such tales!

But I think that it is something more than this too.

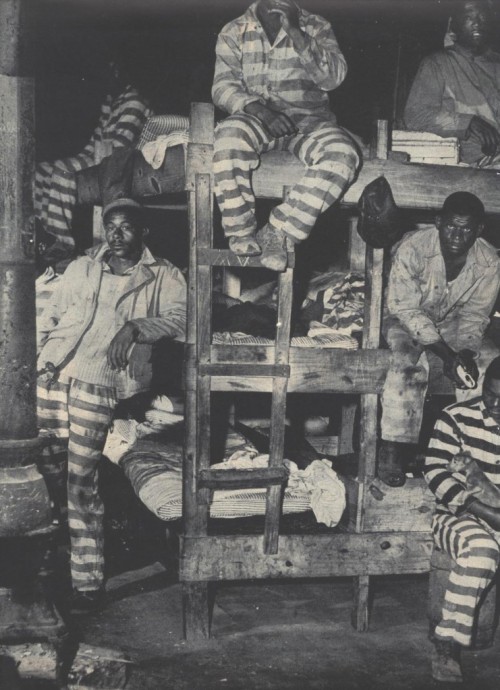

“My name is Assata Shakur, and I am a 20th century escaped slave.” — These are the words that begin “An Open Letter” penned by Shakur in 1998.

Assata Shakur stands defiantly in opposition to her oppression and subjugation by the State. Joy James makes a salient point: “Shakur is singular because she is a recognizable female revolutionary, one not bound to a male persona (p.138).” She adds: “Along with Harriet Tubman, Shakur would become one of the few black female figures in the United States recognized as a leader in an organization that publicly advocated armed self-defense against racist violence (p.139).”

Joy James’ characterization of Assata Shakur provides a clue into what might be attractive to a young woman like Brittany. As a young black woman of 16 years old living in poverty, I think that it is easy to feel invisible, overlooked, and yet maligned. The singer Jill Scott lamented in an interview a few years ago that “black women are so out of style.” Yet in reading about Assata, Brittany could imagine a black woman being unapologetically black. Assata Shakur is not “out of style.” She has resisted being commodified like other leaders of the Black Panther Party or Black Freedom Movement. Her call for revolution still rings loudly.

In her autobiography, Assata recalls making tape of an essay that she wrote titled “To My People.” In it, she explains her role in the black revolutionary struggle. That statement ends with these powerful words:

It is our duty to fight for our freedom.

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains.

These are still words to live by in the 21st century. They help to make Assata Shakur still relevant to a 16 years old girl living on the West Side of Chicago…

Update: It looks like my friends at the Black Youth Project also had Assata on their minds today. Here’s a post about her from them.