A Dispatch from ‘Occupied Territory’:James Baldwin & The ‘Harlem Six’

Yes, yes, I already know what you are thinking…

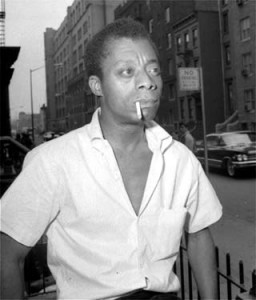

You are thinking: “What is it with this woman and her obsession with James Baldwin?” Well, I won’t give you the one million reasons why Baldwin is awesome. I’ll save that for another post. I will only say that Baldwin was and remains incredibly relevant to understanding America. That should be a good enough reason for my near constant citing of his work. He was one of a kind. Think about it: “Who is our Baldwin today?” It’s a rhetorical question.

You are thinking: “What is it with this woman and her obsession with James Baldwin?” Well, I won’t give you the one million reasons why Baldwin is awesome. I’ll save that for another post. I will only say that Baldwin was and remains incredibly relevant to understanding America. That should be a good enough reason for my near constant citing of his work. He was one of a kind. Think about it: “Who is our Baldwin today?” It’s a rhetorical question.

Because I am working on something about Harlem community members’ resistance to police violence (set to be released on May 7th), I have been immersed in reading about the neighborhood. Today, I am moved to write about a long-forgotten incident that took place in 1964: the case of the Harlem six.

Baldwin writes about the case in an article titled “A Report from Occupied Territory” that was published in the Nation magazine in 1966. The article opens with these paragraphs:

On April 17, 1964, in Harlem, New York City, a young salesman, father of two, left a customer’s apartment and went into the streets. There was a great commotion in the streets, which, especially since it was a spring day, involved many people, including running, frightened, little boys. They were running from the police. Other people, in windows, left their windows, in terror of the police because the police had their guns out, and were aiming the guns at the roofs. Then the salesman noticed that two of the policemen were beating up a kid: “So I spoke up and asked them, ‘why are you beating him like that?’ Police jump up and start swinging on me. He put the gun on me and said, ‘get over there.’ I said, ‘what for?’ ”

An unwise question. Three of the policemen beat up the salesman in the streets. Then they took the young salesman, whose hands had been handcuffed behind his back, along with four others, much younger than the salesman, who were handcuffed in the same way, to the police station.

The incident that Baldwin writes about took place two years before he published his essay in the Nation and came to be known as the “Little Fruit Stand Riot.” The young salesman that Baldwin quotes in his piece was Frank Stafford, a 31 year old door-to-door salesman, who was arrested and brutally assaulted by police when he and a 47 year old Puerto Rican seaman named Fecundo Acion came to the aid of three black teens charged by the cops with overturning a fruit cart owned by Edward DeLuca. A young man named Wallace Baker also witnessed the incident and jumped in to assist a young man who was being beaten by police; Baker found himself assaulted and arrested too.

Several days after this incident, a white couple who owned a second hand store in Harlem was attacked. Frank and Margit Sugar were both stabbed several times. Mrs. Sugar died from her wounds while her husband would be saved by doctors at Harlem Hospital. Within just a few hours, the police had rounded up several young people who they had identified as having been at the scene of the “Little Fruit Stand Riot” that had taken place days earlier. Included in the group were: Wallace Baker (who had been a witness to the “fruit stand” incident) and a few of his teenage friends – Daniel Hamm, William Craig, Ronald Felder, Walter Thomas, and Robert Rice. Police also brought in Robert Baron, a former prisoner who lived in the community.

The NAACP declined to take on the case, even though it seemed clear from the beginning that the young men were in the process of being railroaded, so a local attorney named Conrad Lynn tried to assemble a defense team to handle the trials of the young men. William Kunstler, who would later become famous for defending Black Panther Party members and Attica prisoners, volunteered to represent the young men at trial. However, the young men were instead assigned public defenders. This fact would prove very important later.

The trial for the young men who would come to be known as the Harlem Six began in March 1965. Harlem was a community that was still roiling from the aftermath of the 1964 riots. It was against this backdrop that the young men were being tried. A black reporter at the New York Times falsely claimed that the six young men had “sworn a blood oath to murder white people.” The Harlem Six then became known to the wider community as the “Blood Brothers.” They were found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

William Epton, who I have previously written about, helped found the Harlem Defense Council, which took the lead in the struggle to free the Harlem Six. The Defense Council raised money and tried to keep the case in the news.

Three years after the young men were convicted, Lynn, Kunstler and others mounted an appeal and were thrilled when the convictions were reversed and new trials ordered. However, Lynn and his associates were again not permitted to represent the young men at their new trials. Two of the six were tried separately and found guilty again. The other four went on trial in February 1971. The trial ended with a deadlocked jury so the judge declared a mistrial. Another trial also ended with a deadlock. Bail was set at $75,000 for each defendant. They could not afford to post this amount and had by this time already spent 8 years in prison. In the end, all of the young men were released from prison after having lost years of their lives unjustly locked behind bars. James Baldwin, Ossie Davis, and many others had played a role in helping to ultimately free the Harlem Six.

For those who want to learn more about this case, you can read Truman Nelson’s article published in Ramparts Magazine in 1965 titled “Torture of Mothers.”

Baldwin always wrote with passion and moral clarity. For me the power of his work is that it always seemed as if he had a deep investment in what he was writing about or commenting on. Below, for example, he explains his interest in the case of the Harlem Six:

This means that I also know, in my own flesh, and know, which is worse, in the scars borne by many of those dearest to me, the thunder and fire of the billy club, the paralyzing shock of spittle in the face, and I know what it is to find oneself blinded, on one’s hands and knees, at the bottom of the flight of steps down which one has just been hurled. I know something else: these young men have been in jail for two years now. Even if the attempts being put forth to free them should succeed, what has happened to them in these two years? People are destroyed very easily. Where is the civilization and where, indeed, is the morality which can afford to destroy so many?

As Baldwin writes about the tactics that law enforcement deployed against black people in Harlem, I dare you not to find echoes in our current situation:

But the police are afraid of everything in Harlem and they are especially afraid of the roofs, which they consider to be guerrilla outposts. This means that the citizens of Harlem who, as we have seen, can come to grief at any hour in the streets, and who are not safe at their windows, are forbidden the very air. They are safe only in their houses—or were, until the city passed the No Knock, Stop and Frisk laws, which permit a policeman to enter one’s home without knocking and to stop anyone on the streets, at will, at any hour, and search him. Harlem believes, and I certainly agree, that these laws are directed against Negroes.

There is nothing else to add. If you’ve never read, Baldwin’s “A Report from Occupied Territory,” what are you waiting for? Do it today, do it now.