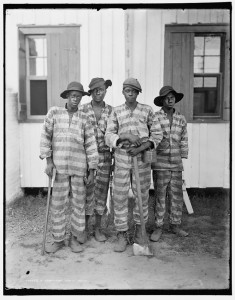

The State As ”Collective Slavemaster:” Criminalizing Black People After Emancipation

As I begin to think about pulling together an exhibition about confinement and captivity in black life, I am re-reading several books and articles about slavery and emancipation.

In Alabama, even before the Civil War, prisoners were responsible for their own court and incarceration costs at the county level. After the Civil War, this continued with one day in prison costing thirty cents. If prisoners could not pay, they served extra time and labored to pay the fees. While Alabama state prisoners had always worked, the state had never made a profit off their labor. This changed in 1875 when the state began to lease out prisoners for their labor to coal mines and to railroad companies. This money was essential to Alabama as the state was broke in the 1870s and prisoner labor helped to fill its coffers.

Alabama like many other Southern states desperately needed laborers for the lease system to work and they used the criminal code as a tool of racial discrimination. One cannot understand the racial subordination of black people post Emancipation without also exploring its links to the need in the south for a cheap and stable labor supply. Adolph Reed (1996) has described the state post-Emancipation as a “collective slavemaster.” This is an important insight that underscores the link between slavery and the continued criminalization of black bodies.

Post-Emancipation the criminalization of black people found its best expression in the Black Codes. In his book “Worse Than Slavery” (which I think is a must read), David Oshinsky suggests that the goal of the Black Codes was:

to control the labor supply, to protect the freedman from his own “vices,” and to ensure the superior position of whites in southern life…The Black Codes listed specific crimes for the “free negro” alone: “mischief,” “insulting gestures,” “cruel treatment to animals,” and the “vending of spiritous or intoxicating liquors.” Free blacks were also prohibited from keeping firearms and from cohabitating with whites…At the heart of these codes were the vagrancy and enticement laws, designed to drive ex-slaves back to their home plantations. The Vagrancy Act provides that “all free negroes and mulattoes over the age of eighteen” must have written proof of a job at the beginning of every year. Those found “with no lawful employment…shall be deemed vagrants, and on conviction…fined a sum not exceeding…fifty dollars.” The Enticement Act made it illegal to lure a worker away from his employer by offering him inducements of any kind.

Another example of manipulating the criminal code to control and subordinate black people is Mississippi’s 1876 “Pig Law” which lowered the threshold for grand larceny and resulted in a quadrupling of convicts in the state in just a few years. The “Pig Law” is discussed in the excellent recent documentary “Slavery By Another Name.”

Watch Pig Laws and Imprisonment on PBS. See more from Slavery by Another Name.

Using the criminal code to steal free labor from black people allowed many Southern states to recover economically after the civil war. The convict lease system was brutal and the lessees had little incentive to safeguard the lives of prisoners. If one died, he/she could easily be replaced by another. The Lease system engendered a great deal of resistance from black people and their allies. For those who are interested, you can read Frederick Douglass’s words about the cruel system here. In the early 20th century, Alabama women were actively struggling to end convict leasing. I’ve written about some of those efforts here.I will have more to say about the convict lease system in the coming weeks…