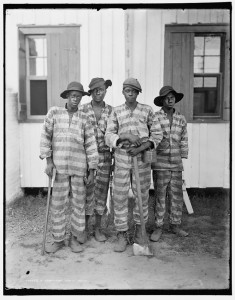

I have not written about the Marissa Alexander case on this blog though I have been closely following the developments in her trial. Well on Friday, Ms. Alexander was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

For those who are unfamiliar with the case, here is a very brief summary. Marissa Alexander is an African-American mother of 3 who tried to protect herself from an abusive husband by firing a warning shot into the ceiling after he had beat her up again. There is of course much more to the case including the fact that her attorney tried to use the infamous “Stand Your Ground” law as her defense and was prohibited from doing so by the judge. You can read much more about the case here.

This is another example of the system re-victimizing survivors of violence and speaks to what I wrote about on Monday with respect to the inadequacy of the efforts to actually support survivors of rape and domestic violence. This case brings to mind countless other stories of battered women and rape survivors who I have known over the years. But there is also something more…

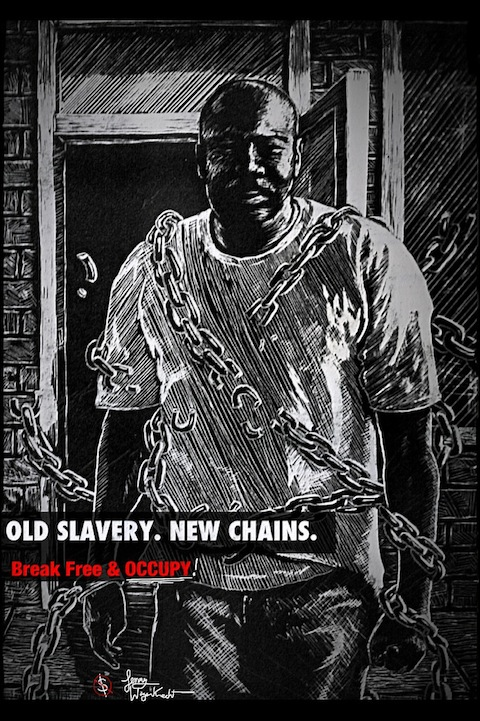

Danielle McGuire has written in her excellent book “At the Dark End of the Street” that there was a time in this country when it was presumed that black women could not be raped. The idea was that they were naturally promiscuous and that their bodies were inviolate. In other words, no never meant no for black and brown women (and some poor white women). This idea has carried over, I think, to the concept of “self-defense” as applied to women of color. If black women’s bodies can always be violated and if black women are easily killable, then the notion of self-defense can never apply. Black women do not have a “self” worth defending.

A poem by Toi Derricotte titled “On the Turning Up of Unidentified Black Female Corpses” is one of my favorites. It captures the idea that black women in our culture are so thoroughly devalued that our deaths go unnoticed and unpunished. One particular stanza is especially moving for me:

a black woman, there is a question being asked

about my life. How can I

protect myself? Even if I lock my doors,

walk only in the light, someone wants me dead.

Read the entire poem if you have a moment, you won’t be sorry.

The Marissa Alexander case brings to mind another instance of self-defense by a survivor of sexual violence. Inez Garcia was a 30 year old Latina who had a child and was profoundly Catholic. Inez was an illiterate woman who had moved to California to be closer to her husband who was incarcerated in Soledad prison. In March 1974, she was beaten and raped by two men in California. She was tried for first degree murder for shooting and killing one of her rapists. A flyer created by her defense committee in the 70s describes the details of the incident.

Louis Castillo and Miguel Jimenez came to Inez’s house at 8 p.m., allegedly to talk to Fred Medrano, who was also renting the house [that Inez lived in]. While waiting for him, the two men started drinking and taunting Inez. When Fred arrived home, he was harassed and threatened and beaten up in the fight that followed. Inez, frightened, told Louis and Miguel to leave, and stepped outside to make sure they left. They forced her to come behind the house with them where, trapped, she was beaten, her clothes torn, and she was raped.

In a state of shock and hysterical from the attack, Inez went back inside and loaded her .22-caliber rifle. At this time she received a phone call from the two men who had just attacked her. They threatened to make it worse for her if she did not leave town. About one half hour later she found her attackers five blocks away, beating up Fred a second time. She saw Jimenez draw a knife and called out. Jimenez turned and threw the knife in her direction. Inez fired, killing Jimenez and missing Castillo completely.

Christa Donaldson Arrested at Inez Garcia Demonstration, San Francisco, 1975

Women’s rights advocates and others seized on the Garcia case as an example of the “justice” system run amok. Her

Defense Committee (comprised of local feminists and other community members) maintained that it was unjust that Inez was accused of premeditated murder “for defending herself against brutal and senseless attack” while her rapist remained free. They added:

“Thousands upon thousands of women have been attacked and raped, and countless more live in fear of rape. Inez is one of the few to defend herself so bravely. Her case is an example to everyone, for until men stop attacking women, women must be free to defend themselves by whatever means necessary.”

Inez Garcia Marching in the Lesbian and Gay Freedom Parade, San Francisco, 1976

Inez Garcia was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to five years in prison. This sparked several “Free Inez” demonstrations. She spent two years behind bars until her conviction was reversed on appeal because the judge had instructed the jury not to consider her rape. Her case was retried in 1977 and she was acquitted. The Garcia case and the Joan Little case offer examples which illustrate that it matters what people on the outside do when unjust charges are brought against individuals. If you doubt this, I suggest that you read Vikki Law’s interview about three cases (including Garcia’s and Little’s) where outside pressure and activism helped to overturn convictions of women survivors of violence. Let’s hope that those fighting on behalf of Marissa Alexander will also be successful in securing a reversal of her conviction on appeal. You can sign a petition to Free Marissa Alexander here