Laura Scott in Old Los Angeles…

I am super busy right now and summer is just around the corner. I set a deadline of early July to be done with my Laura Scott research project so I am going to use the blog over the next few weeks to push myself to meet my goal.

Below I continue my chronicles about Laura Scott’s life…

In Los Angeles, the black community grew from 134 in 1870 to 188 in 1880. By 1900 there were over 2,000 blacks in the city; a more than tenfold increase from 1880. This growth took place as Los Angeles was becoming an industrial city. By 1910, the black population in L.A. was over 7,500. Still black people made up less than 2 percent of Los Angeles’ total population until after World War II.

Women comprised the majority of blacks in Los Angeles from 1900 through 1920 (de Graaf, 1980). Most of these black women were married. Historian Lawrence B. de Graaf (1980) explains that: “In Los Angeles, at the turn of the century, single women were so scarce that black men ‘inspected’ incoming trains for possible mates (pp.288-89).” Western black women also tended to be older and more urban than their counterparts in other regions of the U.S.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, blacks in Los Angeles still experienced discrimination in several spheres. Some restaurants refused to serve blacks and some stores would not cater to them. However because of a housing boom, those who had the means were able to purchase and own property. Many black people took advantage of this opportunity. Even in Los Angeles’ early history, there existed a black elite. These free blacks established their own businesses, bought up acres of land, and formed cultural and social organizations. One of the most well-known black Angelenos of the 19th century was a woman named Biddy Mason who was born a slave, became a nurse/midwife and went on to make a fortune by investing in real estate.

We don’t know exactly when Laura Scott migrated from Alabama to California. The first documented sighting of her in California may have been in 1902. According to a newspaper account, a Laura Scott was arrested for shoplifting in San Francisco in December 1902. It is impossible to know if this is our Laura.

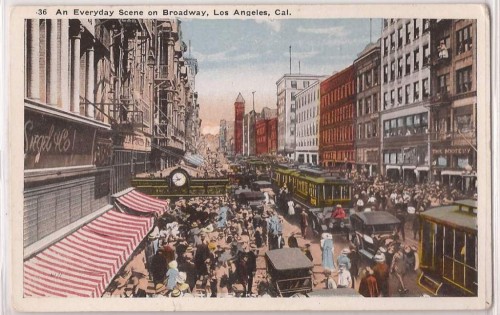

Los Angeles would likely have been seen by a woman like Laura Scott as “the land of milk and honey.” She was born in Alabama’s Black Belt after Emancipation and Los Angeles in the early 20th century was becoming a bustling urban center.

Laura joined other black people in traveling West to search for more freedom and better opportunities. De Graaf (1980) describes the journey west as “dreary and dangerous (p.290).” It is one that most black women didn’t attempt. The difficulty of traveling was only one reason. Many black women also had strong ties to their families and were very reluctant to be separated from them. This led to many of them remaining in the South even after Emancipation (Guttman, 1977). For whatever reason, Laura Scott did not feel the same need to remain near her kinfolk in Alabama. She decided to make her way out West. Why she did this and exactly when she first arrived in California are unknown to us.

According to the 1910 Federal census, Laura Scott was literate; she could read and write. Available prison records describe her education as poor or fair (depending on the year), she seems only to have completed grade school at a public school. It is possible that she received her grade school education at one of the Freedmen Bureau schools established in Alabama after the Civil War. Regardless, Laura Scott did not have the benefit of being highly educated. What type of work could a poorly educated black woman secure in Los Angeles?

In an essay in the anthology “Black Los Angeles,” Paul Robinson (2010) explains how limited the employment options were for blacks in the city:

“Early twentieth-century Los Angeles did not offer the abundance of industrial jobs that characterized other major U.S. cities, and as a result blacks were disproportionately represented in the menial services. Nearly a third of employed black males in Los Angeles in this period worked as janitors, porters, waiters, or house servants. Others worked as horsemen and later as chauffeurs, but only a few were conductors or motormen, the higher level transportation jobs. Even greater discrimination occurred in the booming retail trade industry. By 1910 retail trade had become the largest source of employment in Los Angeles. At that time there were 6,177 store salesmen working in the city, of whom only eight were black…Blacks seeking retail employment faced overwhelming competition from European and Mexican immigrants in the early twentieth century, which was accompanied by discriminatory hiring by management.”

Employment opportunities for black women in early Los Angeles were even more scarce than they were for men. De Graaf (1980) suggests that “servant, laundress, dressmaker and midwife were four of the leading occupations of western black women (p.298).” It wasn’t until 1918, for example, that Los Angeles County Hospital opened the doors of its training program to the first black woman. On various official documents, Laura Scott’s occupation is listed as “house-girl/dress-maker/seamstress.” How much money was she able to make by sewing or cleaning houses? Was it enough to support herself? If not, one has to wonder about how else Laura supplemented her income. By all accounts, she was a woman living alone in a boarding house. It seems unlikely that the men, like Charles Carson, who she brought to her room to spend the night were there to simply play cards.

Some Southern Black women who migrated after the end of slavery found themselves enticed or drawn to prostitution as a way to survive. Darlene Clark Hine (1994) suggests that: “Too many autobiographies and other testimony document the place and the economic functions of prostitution in urban society to be denied (p.99).” She adds: “Young, naïve country girls were not the only ones vulnerable to the lure of seduction and prostitution. Middle-aged black women also engaged in sex for pay, but for them it was a rational economic decision (p.100).” Prostitution among black women in the West was not particularly prevalent. Lawrence de Graaf observes that: “[It] deserves consideration less as a condition which was widespread than as a potential image which many of them [black women] feared could be imposed upon all of them (p.303).” In other words, black women in the West were very concerned about being viewed as sexually promiscuous and worried about the negative impact that this perception would have on their lives. Laura Scott, however, didn’t seem particularly concerned with how she was viewed by others.

Women’s gender roles in early 20th century California were prescribed and rigid. Historian Linda Parker (1992) provides some insight into life for women in California during this period:

“Before 1910 the women of California, like people in other states, lived under state laws that favored male dominance. Many towns enacted laws prohibiting women from wearing men’s clothing even though shirts and trousers were more comfortable and practical for a number of occupations, including farm work. In a typical marriage, fathers assumed sole guardianship of all children, including their care, education, custody and services. Community property of a marriage was also controlled by the husband. He could not sell it without the wife’s consent but he could will one-half of it away. If the wife died first she had no rights to convey her share of the property. Although women paid taxes, they could not vote in California until 1911. Women accused of law violations were ‘arrested by men, imprisoned with men…tried in a court by men lawyers, jurors, and judges according to man-made laws.’”

Laura Scott seems to have eschewed the conventions of her time. She was divorced and did not have any children. Prison records and press reports suggest that Laura drank regularly and perhaps even heavily. She was also a smoker. These habits would have put her outside of the boundaries of acceptable behavior for a woman of her time. Her drinking may have in fact contributed to her numerous encounters with the law… [to be continued…]