Of Kitchenettes and Black Death: Illustrating the Structural Roots of Violence

I have a complicated relationship with Richard Wright. But that is a story for another day. Still, I admire him greatly as a thinker and writer.

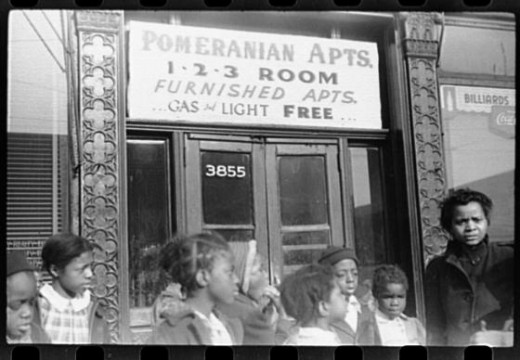

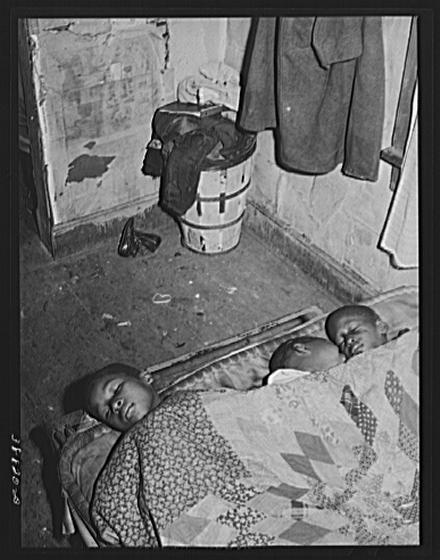

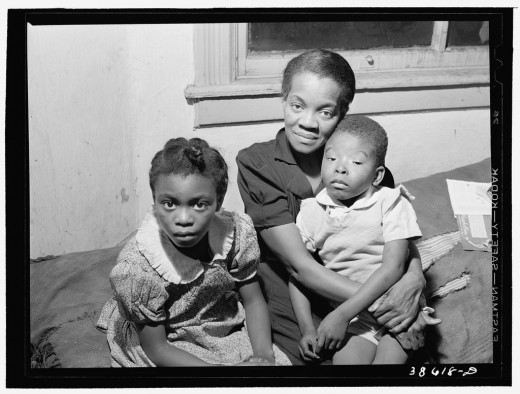

In 1941, he published a book titled “12 Million Black Voices.” In it, Wright brought together his words about the condition of black people in America with some amazing photographs from the WPA. I love this book for a number of reasons including the fact that he makes the history of black people in America accessible and understandable.

When I first read the book many years ago, I was particularly struck by several paragraphs where Wright masterfully distills how structural oppression manifests in individual lives. I haven’t come across a better and more simple illustration of the impact of structural violence in the lives of black people since. So today, I thought that I would share a few of those paragraphs on the blog.

…[T]he Bosses of the Buildings take these old houses and convert them into “kitchenettes,” and then rent them to us at rates so high that they make fabulous fortunes before the houses are too old for habitation. What they do is this: they take, say, a seven-room apartment, which rents for $50 a month to whites, and cut it up into seven small apartments, of one room each; they install one small gas stove and one small sink in each room. The Bosses of the Buildings rent these kitchenettes to us at the rate of, say, $6 a week. Hence, the same apartment for which white people — who can get jobs anywhere and who receive higher wages than we — pay $50 a month is rented to us for $42 a week! And because there are not enough houses for us to live in, because we have been used to sleeping several in a room on the plantations in the South, we rent these kitchenettes and are glad to get them. These kitchenettes are our havens from the plantations in the South. We have fled the wrath of Queen Cotton and we are tired.

Sometimes five or six of us live in a one-room kitchenette, a place where simple folk such as we should never be held captive. A war sets up in our emotions: one part of our feelings tells us that it is good to be in the city, that we have a chance at life here, that we need but turn a corner to become a stranger, that we no longer need bow and dodge at the sight of the Lords of the Land. Another part of our feelings tells us that, in terms of worry and strain, the cost of living in the kitchenettes is too high, that the city heaps too much responsibility upon us and gives too little security in return.

The kitchenette is the author of the glad tidings that new suckers are in town, ready to be cheated, plundered, and put in their places. The kitchenette is our prison, our death sentence without a trial, the new form of mob violence that assaults not only the lone individual, but all of us, in its ceaseless attacks.

The kitchenette, with its filth and foul air, with its one toilet for thirty or more tenants, kills our black babies so fast that in many cities twice as many of them die as white babies. The kitchenette is the seed bed for scarlet fever, dysentery, typhoid, tuberculosis, gonorrhea, syphylis, pneumonia, and malnutrition.

The kitchenette scatters death so widely among us that our death rate exceeds our birth rate, and if it were not for the trains and autos bringing us daily into the city from the plantations, we black folks who dwell in northern cities would die out entirely over the course of a few years.

The kitchenette, with its crowded rooms and incessant bedlam, provides an enticing place for crimes of all sort — crimes against women and children or any stranger who happens to stray into its dark hallways. The noise of our living, boxed in stone and steel, is so loud that even a pistol shot is smothered.

The kitchenette throws desperate and unhappy people into an unbearable closeness of association, thereby increasing latent friction, giving birth to never-ending quarrels of recrimination, accusation, and vindictiveness, producing warped personalities.

The kitchenette injects pressure and tension into our individual personalities, making many of us give up the struggle, walk off and leave wives, husbands, and even children behind to shift as best they can. The kitchenette creates thousands of one-room homes where our black mothers sit, deserted, with their children about their knees.

The kitchenette blights the personalities of our growing children, disorganizes them, blinds them to hope, creates problems whose effects can be traced in the characters of its child victims for years afterwards.

The kitchenette jams our farm girls, while still in their teens, into rooms with men who are restless and stimulated by noise and lights of the city; and more of our girls have bastard babies than the girls in any other sections of the city.

The kitchenette fills our black boys with longing and restlessness, urging them to run off from home, to join together with other restless black boys in gangs, that brutal form of city courage.

The kitchenette piles up mountains of profits for the Bosses of the Buildings and makes them ever more determined to keep things as they are.

The kitchenette reaches out with fingers full of golden bribes to the officials of the city, persuading them to allow old firetraps to remain standing and occupied long after they should have been torn down.

The kitchenette is the funnel through which our pulverized lives flow to ruin and death on the city pavements, at a profit…(p. 104-111)

As a sociologist, all I could do after reading this passage was to slow clap and hang my head. Honestly, in just a few words, Wright expresses what would take me a dissertation to describe. This is what black genius looks like. When I have tried to get my students to understand root cause analysis, I have used this excerpt as a teaching tool. It never fails to get them to better understand the nature and implications of structural oppression. This is a testament to the fact that Richard Wright’s words are as relevant today as they were in 1941.

For those who are interested, below are some of the photographs that accompanied Wright’s words.

More photos from the whole book can be found here.