The Soledad Brothers Defense Committee: A Brief Consideration

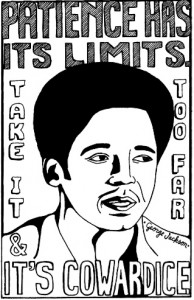

In January 1970, three black inmates at Soledad Prison in California were killed. A guard named O.G. Miller was accused of the crime and then exonerated of the murders. Shortly after prisoners at Soledad heard about this development, a white guard named John V. Mills was found dying in the television room of the prison. He had been severely beaten and seemed to have been thrown from the third floor tier into that room. Mills later died. Right away, prison officials suspected retaliation for the death of the three black prisoners. They accused three Soledad prisoners, Fleeta Drumgo, John W. Clutchette, and George Jackson of Mills’s death.

Jackson was at Soledad serving a one-year-to-life prison sentence for a robbery he committed at 17. By this time, he had already spent 10 years behind bars for that crime. He was a victim of California’s indeterminate sentencing laws. All three prisoners maintained their innocence and their case became a cause celebre across the country but particularly in California. Several Soledad Brothers Defense Committees were established.Angela Davis, famously, became a member of a Soledad Brothers Defense Committee in the Bay Area and began to correspond with George Jackson. She credits that relationship with sparking her interest in understanding the political functions of prisons.

Prisoner defense committees have a history that dates back to the 1920s. They have played an important role over time in bringing attention to unjust prosecutions and convictions. I have written about the role that American Communists have played in setting up such committees particularly for black prisoners. The Scottsboro Defense Committee, for example, was one of the most prominent of these.

Years ago, I befriended a man who had been one of the founding members of the San Francisco Soledad Brothers Defense Committee. He has since passed away but he shared many stories with me, mostly as cautionary tales. He had become deeply disillusioned with prison reform and had basically dropped out of activism by the time I met him. I think that he saw something of the idealism that he used to feel in me at the time. I was 22 years old when we met. I was living in New York and I was feeling my power as a young organizer. I have wanted to write something about some of the lessons that he imparted to me for a long time, however I have been putting it off. I’ll have to get to that project in the near future.

The man had been friendly with a radical lawyer named Fay Stender. Stender was one of George Jackson’s lawyers and was instrumental in getting his letters published in his famous book titled “Soledad Brother.” Stender was brutally assaulted and shot several times at close range in 1979 by a former prisoner named Edward Glenn Brooks. Brooks, a member of the Black Guerilla Family, a group originally founded by Jackson, is reported to have forced Stender to state: “I, Fay Stender, admit I betrayed George Jackson and the prison movement when they needed me most” just before he shot her. Stender suffered so much pain from her injuries that she killed herself in 1980, almost a year to the date that she had been shot. If you want to read more about Fay Stender’s horrific ordeal, I suggest that you read this chilling essay by Diana Russell.

The man who shared his experience of working with the Bay Area Soledad Brothers Defense Committee told me that Stender’s assault was his final breaking point. Like many on the left in his era, he had come to believe that all prisoners were political prisoners of a sort. It didn’t matter how they came to be locked up. The idea was that the racist and classist American system specifically targeted the poor, the black, and the brown with unfair laws. Prisoners were victims of circumstance. This is grossly simplifying these ideas but you get the gist. The man told me that this idea was shattered for him by Edward Brooks’s actions.

The truth is, however, that he had begun to be disillusioned with prison reform much earlier. The California Soledad Brothers Defense Committees, particularly in San Francisco and Santa Cruz, were rife with conflict. Conflict between family members of the Soledad Brothers and the mostly white organizers of the Defense Committees. Conflict between members of the Defense Committees themselves.

One of my prized possessions is a copy of a letter dated June 23rd 1971 that clearly lays out some of these conflicts and also seeks to define the mission of the Soledad Brothers Defense committees. It is fascinating. The letter was written by members of the San Francisco committee, in response to accusations leveled against them by the family of George Jackson in particular. The letter opens with these words:

“At our regular Tuesday committee meeting Mrs. Jackson, Penny Jackson, Derrick Maxwell, two of Derrick’s sidekicks Leo and Dawit, and four members of the Black Panther Party came in very cold and gruff. On the agenda was the discussion of a concrete plan of action: what the committee should do. Mrs. Jackson made a motion to dispense with everything else on the agenda and deal with restructuring the committee. She was disappointed with the present structure of a steering committee appointed by the people. She suggested having one person who is strong-willed, who has a strong character who could run the office and not allow people’s problems rising to a level that prevented committee work. Penny agreed with the restructure. It was her contention that the steering committee was a “clique”, and it was her idea to oust the “clique” and replace it with nothing. There were no suggestions from Derrick. To back up her statements Penny claimed no work was being done by the S.F. committee and no money was being turned over by the S.F. committee. Penny and Georgia claimed the committee was going broke…”

The letter goes on to offer a statement by the S.F. Committee in defense of itself and countering the claims made by the Jackson family. It is engrossing and for folks who are historians of the prison reform movement of the 60s incredibly enlightening. I’ve thought about turning the letter over to an archive somewhere but I assume that it would be hidden from public view in an institution that is inaccessible to ordinary people. So for now, it remains in storage with my other artifacts.

Anyway, I think that the history of prisoner defense committees should be told to help us learn from both the successes and the mistakes of the past. I wish that I had more time to do personal research but for now I hope that someone else is hard at work on a comprehensive history of some of the more famous defense committees.

Note: I will be in Detroit for the next several days attending the Allied Media Conference so blogging will be sporadic at best and maybe even non-existent until next week.