On Watermelons and Black Criminality…

Lately, it has been more challenging than usual to talk with black youth (in particular) about how entrenched the idea of criminality as an inherent marker of blackness is in American culture. As I have been thinking more seriously about how to better convey this idea as a longstanding and enduring one, I turned to my collection of postcards and images associating black people and watermelons.

What do black people and watermelons have to do with representations of black criminality you might ask? Good question. Actually a lot. As David Pilgrim who is the curator of the Jim Crow Museum points out, the association of black people and watermelons became a popular representation at the turn of the 20th century among white people. Thousands of postcards, advertisements, and figurines depicted black adults and children interacting with or actually representing watermelons. It is difficult to overstate how popular these images were and how enduring the stereotype is. The purpose of these watermelon images was to dehumanize black people and to represent them as contented, lazy, “coons.”

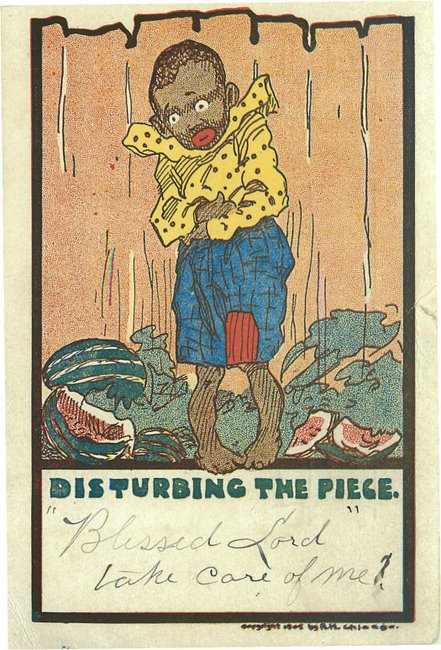

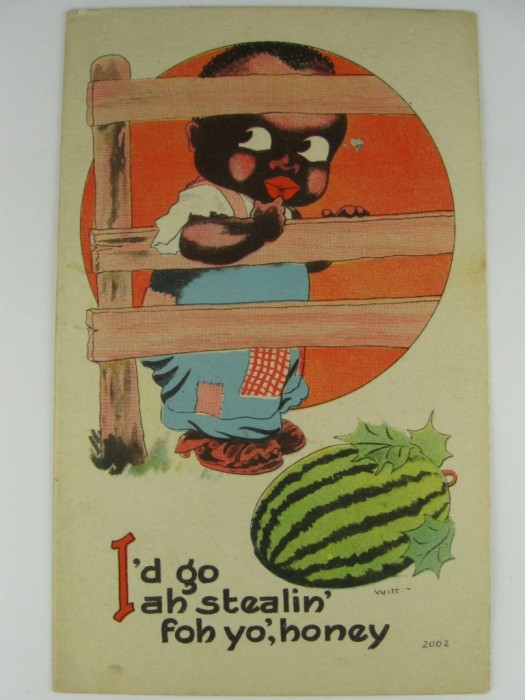

One popular theme (particularly in postcards) was of the black “coon” stealing watermelons. Below is an example of that image.

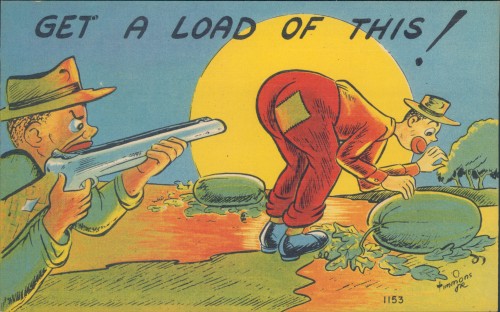

Notice the “disturbing the piece” tag line. This was common. There is a series of postcards promoting the same theme. The play on words suggests that the black person is doing something illegal and criminal. Here is another postcard image showing a black “coon” who is being targeted by a man with a gun:

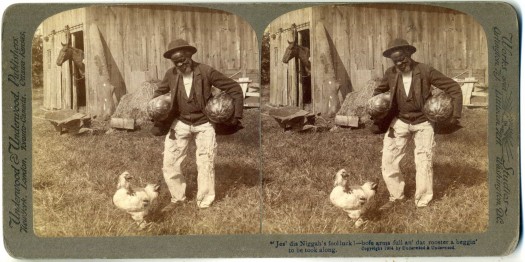

Other postcards and stereoviews make more explicit references to stealing. They reinforced the stereotype of black criminality.

It’s worth asking whether these representations were based in fact. Is it actually the case that newly freed slaves were more criminally inclined than whites?

Mary Ellen Curtin (2000) reviews the literature about black criminality in the South post-emancipation. She references studies that suggest that after slavery ended many blacks turned to theft in order to survive. She cites historian Edward Ayers as “concluding that a black ‘crime wave’ swept Dixie after emancipation (p.43).” She adds:

“Although sympathetic to the plight of black prisoners and aware of how a racist legal system worked to the detriment of blacks, none of these historians challenges the assumption that freed people indeed stole. Ayers, Oshinsky, and Wharton argue, sympathetically, that economic ‘hard times’ led to increased vagrancy and theft among the freedpeople (p.43).”

These scholars, then, give credence to the idea that blacks in the South in fact committed more property crimes than did whites. Curtin, however, doesn’t take these assessments at face value. She complicates other historians’ assumptions by illustrating that sometimes “theft charges also served as subterfuge for political revenge(p.44).” She adds that “criminal charges were used to intimidate assertive blacks (p.44).” Curtin’s research suggests that:

“…criminal charges of theft also concealed deep conflicts between the freedpeople and their political opponents and employers, conflicts that cannot always be seen in the official records (p.44).”

This suggests that southern whites redefined crime and used the law as a tool of social control and revenge to imprison a number of black people. This reframes the idea that southern whites were simply responding to a ‘black crime wave’ of larceny and theft when they imposed new laws like the Black Codes on newly freed black slaves. One can therefore not evaluate the representations of black criminality produced by whites outside of this context. The postcards and other visual representations of blacks stealing watermelons served then to reinforce stereotypes of black people as thieves and criminals more generally. White people had an interest in portraying blacks as lazy, contented, and criminally inclined. This provided justification for punitive laws which could be used to re-enslave the newly freed blacks. Disseminating negative stereotypes about people performs valuable cultural work for those who would use their power to oppress others. Hitler and the Nazis created propaganda that sought to reinforce stereotypes of jews as sub-human. These representations laid the groundwork for claiming that their extermination was justified and even desirable.

I am still trying to determine how I will use my watermelon postcards and other images to engage young people in a discussion about the social construction of black criminality. Stay tuned for more information as I develop my curriculum. In the meantime, feel free to browse through some of my collection here (I just started this project to digitize my postcards and images and will be slowly adding images to the site as I scan them).