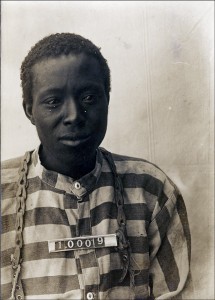

Fear and Loathing in the Arkansas State Penitentiary: A Historical Account

In Arkansas, the whipping of prisoners was permitted by law and as late as the early 1970s was still being practiced. There were a number of tools used to inflict corporal punishment on prisoners including “the strap” which was “more than five feet long, five inches wide, three-eighths of an inch thick with an eighteen-inch wooden handle.” One of the most infamous and cruel instruments of torture used at the prison, however, was a device called “the Tucker Telephone:”

“The telephone, designed by prison superintendent Jim Bruton, consisted of an electric ‘generator’ taken from a crank-type telephone and wired in sequence with two dry-cell batteries. An undressed inmate was strapped to the treatment table at Tucker Hospital while electrodes were attached to his big toe and to his penis. The crank was then turned, sending an electrical charge into his body. In ‘long distance calls’ several charges were inflicted — of a duration designed to stop just short of the inmate’s fainting. Sometimes the ‘telephone’ operator’s skill was defective and the sustained current not only caused the inmate to lose consciousness but resulted in irreparable damage to his testicles. Some men were literally driven out of their minds.

The Tucker telephone was used not only to punish inmates but to extract information from them. One of the two telephones known to be on the farm was found hidden in a hat box on the top shelf of a linen closet in the Big House, where Jim Bruton was living then (Murton & Hyams 1969, 7).”

It won’t come as a surprise to readers that black prisoners were the vast majority of the individuals who were subjected to the “Tucker Phone.” Unfortunately the discovery of this torture apparatus was only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the events taking place at Tucker. Not only were prisoners beaten with leather straps, blackjacks, and hoses, needles were shoved under their fingernails, and cigarettes were applied to their bodies. The report also detailed a list of other horrors that prisoners were subjected to on a daily basis.

In an article titled “Hell in Arkansas,” Time magazine reported on the efforts of a reform-minded superintendent of Tucker prison named Thomas Murton who had been appointed by Governor Rockefeller in 1967. The article outlines what Mr. Murton found upon his arrival at Tucker:

When Thomas Murton, Rockefeller’s 39-year-old reform appointee to the prison superintendent’s job, took over early in 1967, enforced homosexuality and traffic in liquor and narcotics were rampant at Tucker and the Cummins prison farm.

Trusties, armed with shotguns, were squeezing weekly payoffs out of the “rankmen,” or ordinary inmates, who worked under their supervision. Often the trusties, who lived in unlocked TV-and-refrigerator-equipped shacks, fired rifles inches over rankmen’s heads simply for sport. Murton quickly abolished many of the grotesque practices, but he was troubled by continuing rumors that prisoners had been murdered and buried on the prison grounds.

Ultimately, Murton only spent a year as superintendant at Tucker and a year later he published an absolutely scathing indictment of the prison farm in a book titled “Inside Prison U.S.A.” The book is out of print now but if you are a student of penal history, it is a must-read.

If you are curious about what happened to the former superintendent Jim Bruton after he “resigned” from his position when the CID report was released. Here is a short summary from Time Magazine in 1970:

At Arkansas’ Tucker prison farm, “the Tucker telephone” was a fearsome means of communicating the superintendent’s displeasure. It consisted of an old-fashioned crank-phone apparatus that was wired to the genitals and one of the big toes of recalcitrant prisoners. When the crank was spun, the recipient of the message was shocked nearly unconscious. James Bruton, the superintendent who designed and used that device, resigned in 1966 when state officials began a series of investigations of brutality in the Arkansas prisons (TIME, Feb. 9, 1968). Last week Bruton pleaded no contest to charges that he violated prisoners’ civil rights by administering cruel and unusual punishment. The penalty he received was considerably more compassionate than many he himself had dealt out.

The maximum permissible sentence that could be imposed on Bruton under the federal Civil Rights Act of 1871 was a $1,000 fine and one year in prison. Federal Judge J. Smith Henley imposed the full penalty, complained that it was too light, and then made it even lighter. He suspended execution of the prison term and released Bruton on a year’s probation. Henley’s explanation: “The court doesn’t want to give you a death sentence, and quite frankly, Mr. Bruton, the chances of your surviving that year would not be good. One or more of these persons or their friends with whom you have dealt in the past as inmates of the Arkansas penitentiary would kill you.”

Note: I have been wanting to write about Johnny Cash for some time but I can’t seem to find the right angle yet. I have a bit of a Cash obsession; I just love him. He was a bundle of contradictions (like we all are): a self-described “southern-redneck” who was anti-racist before it was cool. Anyway as I try to decide how/what I want to write about him and his prison reform efforts, you should read this article about his important work in reforming the Arkansas prison system.