“Tell Her That It Was All Me…”

On some days, the toll of the work catches up with me… I woke up this morning feeling soul-weary.

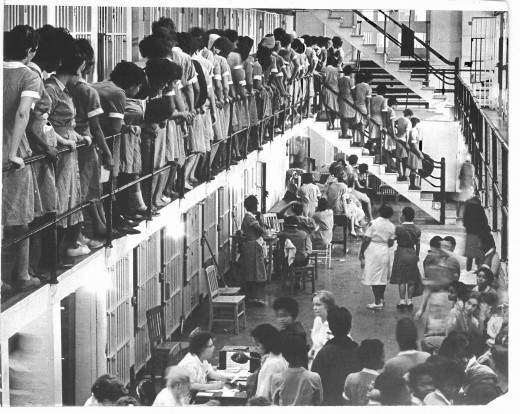

In just the past 10 weeks, two young people who I have worked with have been re-arrested. Both are facing charges of selling drugs and will likely spend time in prison. I know that many don’t want to hear it but this was inevitable. Both young men are now in their early 20s and have no jobs. I don’t know how they are expected to make a living; to survive. The street economy is the only viable path. This is simply the truth.

I finally had an opportunity to visit with one of the young men at Cook County jail on Thursday morning. I plastered a smile on my face when he came out to meet me. I knew that he was feeling depressed. His grandmother told me about this before I went to the jail. When he sat down, he didn’t look at me. His head was bent. In almost a whisper, he said: “Sorry I let you down Ms. K. Sorry…”I said nothing for what might have seemed like two minutes. I finally responded: “You didn’t let me down. I’m sorry that we’ve all let you down.” He looked up and he had tears running down his face. He started furiously wiping them away. We just sat quietly for a few minutes. I told him that I would stop by to see his grandmother and bring her news of how he was. What did he want me to convey to her? I asked.

“Tell her that it was all me.”

I am dragging today. I find that I am questioning myself more and more. What am I doing? It feels like I am putting band-aids on gaping wounds. There is an entire generation of young people, mostly of color and all poor, that is basically disposable in this capitalist system. I am confronted with the wreckage from this ongoing hurricane. Today I am struggling to hold on to some hope. These days happen.

“Tell her that it was all me.”

These words replay in my mind like a mantra. The truth is that the young man is wrong. It was not all him. We have all failed this young man and hundreds of thousands like him. No it was not all him. He attended schools where his teachers barely taught; lived with 8 other people in a two-bedroom apartment; he has been profiled and mistreated by the police since he was 8 years old. No it was not all him.

I am feeling depleted today so I turned to a quote that was shared by a friend who I consider to be one of the best and most ethical youth workers on the planet:

“It is part of our task as revolutionary people, people who want deep-rooted, radical change, to be as whole as it is possible for us to be. This can only be done if we face the reality of what oppression really means in our lives, not as abstract systems subject to analysis, but as an avalanche of traumas leaving a wake of devastation in the lives of real people who nevertheless remain human, unquenchable, complex and full of possibility.” Aurora Levins Morales, Medicine Stories

Today, I struggle to maintain my wholeness in the face of brutalizing systemic oppression. I remain committed to embracing the humanity of the traumatized and profoundly human people who I share space with on earth.

“Tell her that it was all me.”

No sweetheart, I won’t tell her that because it simply isn’t true. I’ll tell her that it is all of us.

Black Women in Unmarked Graves…

Mae Mallory is buried in an unmarked grave in the Frederick Douglass Memorial Park on Staten Island.

She died in 2007. She was 80.

If you are a black person living in the U.S. and don’t know who Mallory is, that’s deeply unfortunate because you stand in part on her shoulders. She spent a lifetime fighting against racial injustice. She divorced in the early 1950s when this was frowned upon. She was a single mother before it was acceptable to be one. She spoke loudly and believed in carrying a big stick. She was radical and unapologetic. She was unjustly jailed and made a big fuss about it.

She is buried in an unmarked grave on Staten Island. Her contemporaries like Robert F. Williams, Julian Mayfield, Huey Newton, Malcolm X have markers on theirs. Mallory hasn’t yet found her Alice Walker who will reclaim the ground where she is buried and remind all of us of her invaluable contributions. After being falsely accused of molesting young boys and savaged by the Black press, Zora Neale Hurston escaped to Florida where she lived a quiet, destitute life until her death. She too was buried in an unmarked grave until Alice Walker revived her legacy. There is something about being a black woman in the U.S. that seems to demand invisibility and also burials in unmarked graves.

I have written about Rekia Boyd as I try to hold myself accountable for minimizing the state violence against black girls and women. Perhaps I want to forget about the violence because I am black and a woman and a survivor of violence. I want to close my eyes to stories like that of 17 year old Kwamesha Sharp who was thrown to the ground by a police officer and then miscarried. If the baby was a girl, I hope that her grave is marked.

Ms. Sharp is suing the officer.

There are no campaigns calling for “justice” for Kwamesha. And you know what? I can’t be critical about this because of the thousands upon thousands of injustices that people of color experience in a year, a month, a week, a day. Who can keep up with all of the instances of violence and abuse and oppression? The answer is simple: no one can. It is going to take a massive and long-term social movement to uproot state violence.

In the meantime, I hope that Rekia Boyd’s grave has a marker on it…

Musical Interlude: Winter in America

One of my very favorite performers is Gil Scott-Heron. I think that this song “Winter in America” is particularly appropriate today on the 4th of July: “And ain’t nobody fighting, Cause nobody knows what to save.”

Coretta Scott King: On Going to Jail…

While I was in Detroit, I of course stopped at a used bookstore. Bookstores are my DOWNFALL. I am scared to even think of the thousands upon thousands of dollars that I have spent on books over the years. Anyway, this bookstore had a set of Jet Magazines from the 60s on sale. I could not pass them up. I just couldn’t. They used to cost 20 cents. So great. Anyway, in the Feb 18 1965 edition, the magazine features an interview with Coretta Scott King as she was left Atlanta to visit her husband who was jailed in Selma. Here is the story:

While I was in Detroit, I of course stopped at a used bookstore. Bookstores are my DOWNFALL. I am scared to even think of the thousands upon thousands of dollars that I have spent on books over the years. Anyway, this bookstore had a set of Jet Magazines from the 60s on sale. I could not pass them up. I just couldn’t. They used to cost 20 cents. So great. Anyway, in the Feb 18 1965 edition, the magazine features an interview with Coretta Scott King as she was left Atlanta to visit her husband who was jailed in Selma. Here is the story:

Community Accountability As “Art Not Science”

This post is going to be disjointed and disorganized. Feel free to skip reading it…

I am back from several days in Detroit where I attended the Allied Media Conference while also visiting friends. It was good to meet so many energetic, smart, and young people who are committed to social justice and transformation.

Today I want to write about the last workshop that I attended on Sunday which focused on how to address sexual violence through community accountability (without relying on police and prisons). The workshop was very ably facilitated by Philly Stands Up! If you don’t know about the organization and its work, you should take some time to familiarize yourself. The collective does wonderful transformative justice work.

Southern “Justice,” Regulators, and Black Resistance…

It has been suggested that between 1890 and 1899, there were an average of two black people a week lynched in the United States. Think about this number for a minute… It’s stomach-turning.

The more one learns about the history of lynching in America and its relationship to the criminal legal system, the more one wants to know. I am particularly fascinated by the ways that black people resisted this horrific violence. Many years ago, while reading a book I can no longer recall, I came across the story of Jack Trice, a black man who refused to allow his son to be “regulated” by a white mob. The story first appeared in an short article was published in a black newspaper called the Cleveland Press Gazette on May 30, 1896.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA — Jack Trice fought fifteen white men at 3 A.M., on the 12th, killing James Hughes and Edward Sanchez, fatally wounding Henry Daniels and dangerously wounding Albert Bruffum. The battle occurred at Trice’s humble home near Palmetto, a town six miles south of here, to prevent his 14-year old son being “regulated” (brutally whipped and perhaps killed) by the whites.

On the afternoon of May 11, Trice’s son and the son of Town Marshal Hughes, of Palmetto, fought, the white boy being badly beaten. Marshal Hughes was greatly enraged and he and 14 other white men went to Trice’s house to “regulate” his little boy. The whites demanded that the boy be sent out. Trice refused and they began firing. Trice returned fire, his first bullet killing Marshal Hughes. Edward Sanchez tried to burn the house, but was shot through the brain by Trice.

Then the whites tried to batter in the door with a log, which resulted in Henry Daniels getting a bullet in the stomach that will kill him. The “regulators” then ran. A final bullet from Trice’s deadly rifle struck Albert Bruffum in the back.

The whites secured re-enforcements and returned to Trice’s home at sunrise, vowing to burn father and son at the stake; but the intended victims had fled. Only Trice’s aged mother was in the house. The old lady was driven out like a dog and the house burned. Posses with bloodhounds are chasing Trice and his boy, and they will be lynched if caught. It is sincerely hoped that both will escape.

How many hundreds or thousands of other Jack Trice’s existed in the United States? Most of these stories of resistance are lost to us.

I made a copy of the newspaper article and pinned it to my bulletin board in my home office. Every time I look up at the board and see this story, I say to myself: “you should really go back to search the newspapers to see whether Jack Trice and his son were in fact caught.” But something always prevents me from moving forward with this research. The truth is I would much rather believe that both successfully escaped than to consider the horrifying alternatives. In this instance, Google is not my friend.

So for today, Jack Trice, I speak your name in the hope that you lived a long and relatively happy life in spite of the trauma that you suffered.