They Burned Down Harlem in ’64…

So apparently, a young man who was handcuffed in the back of a police car was shot and killed. The police are claiming that he committed suicide. Folks all across the country are openly wondering what it will take to stop the slaughter by law enforcement. It’s always instructive to turn to history at times like this. The unjust murder of people of color in particular by the police is not new (as I have written countless times on this blog). Today, my twitter feed has a lot of discussion about whether we might need to meet violence with violence to end these incidents. Let me say that this has been tried in the past. In fact, over and over again throughout our history, community uprisings (sometimes called riots) have been catalyzed by instances of police violence. Such was the case in Harlem in 1964. I wrote a pamphlet about Resistance to Police Violence in Harlem. Below is an excerpt that addresses the Harlem Riots of 1964.

Note: All of the references are included in the pamphlet.

1964 Harlem Riot

On July 16th 1964 at around 9:20 am, 15 year old James Powell and his friends were sitting on a stoop near the Robert E. Wagner, Sr. Junior High School on East 76th street in the Yorkville community waiting for their remedial reading summer class to begin. James and his friends got into a verbal altercation with Patrick Lynch who was the superintendent of three apartment buildings across from the school. Lynch had been watering either some flowers in front of a building or the sidewalk. The man decided to aim his water hose at the young people and allegedly said, “Dirty niggers, I’ll wash you clean.” Lynch was white; James and his friends were black. He continued to drench the young people with water as they scattered and tried to retaliate by throwing a bottle and a soda can in his direction. James Powell had had enough and decided to go after the man, who ran toward a nearby building.

An off-duty police officer, Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan, came upon the scene as he was leaving a repair shop across the street. He saw James Powell chasing Lynch and ran over to assist. Gilligan was not wearing his uniform and without apparently indicating that he was a cop pulled out his gun.

James Powell saw that Patrick Lynch had disappeared into a building and decided to stop his pursuit. When he turned around, he came face to face with Thomas Gilligan, who fired three shots. Powell hit the ground, blood pouring from his mouth. There are conflicting accounts about what happened during the shooting and immediately afterwards.

A friend of Powell’s remembered rushing over to James immediately after he had been shot. He turned to Lieutenant Gilligan and asked: “Why did you shoot him?” According to author, T.J. English: “Gilligan answered, ‘This is why.’ He took a police badge from his pocket and pinned it to his shirt. Then according to the student, Gilligan said, ‘This black bastard is my prisoner. Somebody call an ambulance.’”

When an ambulance did arrive, it was too late. James Powell was dead. Students began pouring out of Wagner Junior High School and running to see the body of their classmate. By the time 75 other police officers had gathered on the scene, over 300 students started throwing garbage cans, bottles, and rocks in anger. The situation was quickly subdued and no arrests were made.

Here’s how the New York Times reported on the incident in an article under the headline “Negro Boy Killed; 300 Harass Police:”

“An off-duty police lieutenant shot and killed a 15-year old Negro boy in Yorkville yesterday when the youngster allegedly threatened him with a knife. After the shooting, about 300 teen-agers, mostly Negroes, pelted policemen with bottles and cans. Before order had been restored by 75 steel-helmeted police reinforcements, a Negro patrolman attempting to disperse the screaming youths was hit on the head by a can of soda. He was taken to Lenox Hill Hospital, where his condition was later reported as good. The shooting occurred at 9:20 a.m. outside a six-story white brick apartment house at 215 East Seventy-sixth Street, opposite Robert F. Wagner Junior High School, where summer school classes were in progress. The dead boy was James Powell, a student at the school, who lives at 1686 Randall Avenue, the Bronx. The police said that youth had been shot twice, in the right hand and in the abdomen, by Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan of Brooklyn’s 14th Division.”

Gilligan “claimed that he showed his badge and fired the first time as a warning shot, firing the next two only after Powell lunged toward him with a knife.” Students disagreed that Powell had a knife but some eyewitnesses thought that he may have lunged towards Lieutenant Gilligan. A knife was later found at the scene (eight feet away from where James Powell was shot with its blade closed).

Black people across New York City viewed this killing as unjustified and as one more in the long line of racist incidents of brutality by the NYPD. The next day a number of protests were organized; in particular, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) assembled a multi-racial group of about 75 people to picket the school and then march to the 19th precinct stationhouse on East 67th street. They were met by about 50 police officers and the rally quickly fizzled.

Saturday July 18th was a sweltering day in New York City. A protest was organized in Harlem. By the early evening, there were about 500 people assembled. Among the protesters on that day was William (Bill) Epton. Epton had been a veteran who fought with honor in the Korean War. He returned and became the chairperson of the Harlem branch of the Progressive Labor Party (PLP), a communist organization.

Once the PLP’s Harlem branch, which had been agitating in street rallies against police brutality for months, got word of the July 16th killing of James Powell, it began distributing thousands of posters proclaiming, “Wanted for Murder, Gilligan the Cop.”

Once the PLP’s Harlem branch, which had been agitating in street rallies against police brutality for months, got word of the July 16th killing of James Powell, it began distributing thousands of posters proclaiming, “Wanted for Murder, Gilligan the Cop.”

At the rally on July 18th, Bill Epton delivered a soapbox speech in which he declared, “We’re going to have to kill a lot of cops, a lot of the judges, and we’ll have to go against their army.” Here are Epton’s own words recounting what he said at the rally:

“What I said was that we must fight back when the cops attack us. I said that the police have declared war on Harlem and Harlem must declare war back on them. They – the judges, the cops, the slumlords, the bosses – are the ones who institute violence and murder against the people. I called – openly and publicly – for revolutionary struggle by the people to defeat that reign of terror.”

After the speeches, some protesters decided to march toward the 28th precinct stationhouse. Janet Abu-Lughod (2007) offers this description of what happened next:

After the speeches, some protesters decided to march toward the 28th precinct stationhouse. Janet Abu-Lughod (2007) offers this description of what happened next:

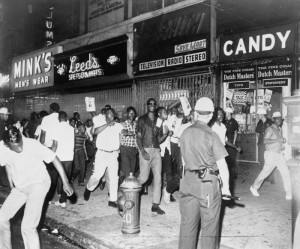

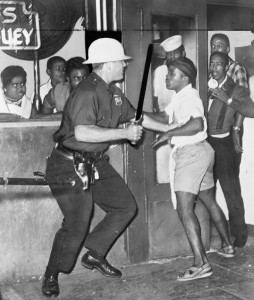

“At the door of the precinct, however, police barred entry, and the crowd was forced to the opposite sidewalk. A committee of five was eventually admitted and demanded the immediate suspension of Gilligan. When the police tried to disperse the crowd, a fight broke out, and a few bottles were thrown from the roofs of tenements nearby. ‘Policemen donned steel…helmets and moved into the tenements, went up the stairs, and took over the roofs, ending the aerial bombardment. Barricades were called for, and…a scuffle broke out, and about twenty-five people, including some policemen, fell to the pavement.’ Some 14 persons were arrested, but this only increased the anger of the gathering and the descent of bottles from the rooftops. And when word of the battle at precinct headquarters reached the rally that was still continuing on 125th Street, it further inflamed emotions. By 10 p.m., the crowd had swelled to an estimated 1,000, and things were getting out of control. ”

The police were brutal in their response to the rebellion. It took three days to get things back under control in Harlem. By Tuesday night July 21st, the riots had moved to Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn. One person died, over 500 were injured and estimates of damages ranged from $500,000 to $1 million dollars.

The police were brutal in their response to the rebellion. It took three days to get things back under control in Harlem. By Tuesday night July 21st, the riots had moved to Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn. One person died, over 500 were injured and estimates of damages ranged from $500,000 to $1 million dollars.

Ultimately, Lieutenant Gilligan was cleared of all charges by a grand jury and went unpunished for his killing of James Powell. It was left to James Farmer, national director of the Congress of Racial Equality, to comment to the New York Times about this outcome: “CORE is astonished that the grand jury, with the compliance of the District Attorney’s office, has seen fit to exonerate a 200-pound police lieutenant in the slaying of a 122-pound Negro Youngster. ” Perhaps the sentiments of the Harlem community were best captured by the words of a leaflet that was distributed at a rally after Gilligan had been exonerated: “Harlem knows that this grand jury decision means that any white policeman who wants to kill a Negro will not have to worry about being tried for murder. ”

Once again, police brutality had instigated a rebellion in Harlem. It wouldn’t be the last time.

In a new song, Jasiri X asks the question: “Do We Need to Start a Riot?” He is in essence asking what it will take to stop the killing of black and brown people by the police. Based on a review of history, community uprisings and rebellions have not successfully ended police violence. We need to find other ways…