In a recent essay, Nicholas Brady laments and explains that black people are being killed with impunity by law enforcement. There is, however, little outcry by the general public against what amounts to a form of genocide. Brady offers an explanation for this:

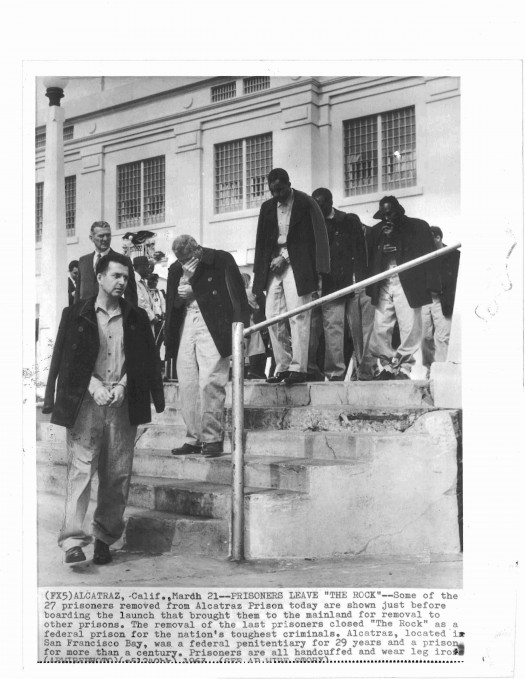

The reason that nobody wants to touch this issue is that it calls into question the ethicality of the entire criminal justice system. When we talk about individual cases we can deal with rogue cops acting in ways “unbecoming” for the police. Yet, returning back to the aforementioned Chamberlain case, we can see how focusing on “rogue” cops mystifies the real problem. Originally all eight officers were exonerated by the grand jury, but now only the officer Hart is being charged for calling Chamberlain a “nigger.” What about the other 7 cops, especially Cantrelli who actually shot Chamberlin for no acceptable reason? The murder cannot be called into question, only the racial epithet used on the scene. The conclusion of the investigation can be summarized as this: the murder of a black man who committed no crime is fair to our procedures. In all of the 120 cases of black people being murdered by the police, security guards, or vigilantes all were either exonerated or were not punished for the murder itself. 120 lives lost are not exceptions, they are the worst statistic of a total system that abuses black people nationally. Whether it is “stop-and-frisk” in New York, “stand your ground” in Florida, or the blue light cameras in Baltimore, the law is systematically and gratuitously watching, intruding, violating, and murdering black people across the nation. It is no longer the lynching rope, but the badge and the gun that is the symbol of violence against black folk.

It’s important to underscore that while there is a lack of outcry in the general population, people of color have been, are, and will continue to agitate on the issue of systemic police violence. We have no choice.

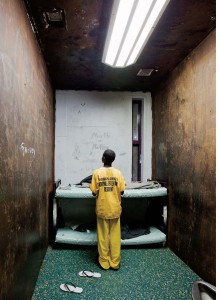

Whenever I ask a young person of color (particularly black youth) to narrate a personal experience of injustice, almost all (with few exceptions) tell a story of police harassment and violence. The youth who I work and interact with, as I have written in the past, mostly want to talk about the police. This is part of the reason that I have been focusing so diligently for the past couple of years on developing tools and resources that can be used by educators, organizers, and community members to address police violence and structural oppression.

A conversation that I had with a young black man who has been recently released from prison produced a light-bulb moment for me. He casually said the following words:

“You know Ms. K, when I was growing up in the hood, I wasn’t afraid of the bogeyman, I was afraid of the 5.0. In the ghetto, the police are the bogeyman.”

The young man’s framing has really stayed with me for the past few weeks. I am once again reminded of why it is so important to listen to the stories and voices of young people. What does it mean for the psyches, health, and well-being of our young people when the bogeyman is real and has almost limitless power?

Below is a short clip of black youth talking about the impact of their encounters with the police. Please take three minutes to listen to what they have to say. Then recall the words of the young man cited above. For many black youth, the bogeyman is very, very real…

Impact of Policing on Youth of Color from Mariame Kaba on Vimeo.

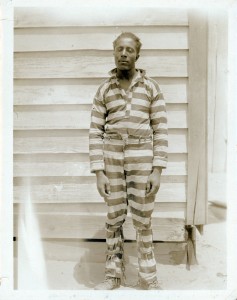

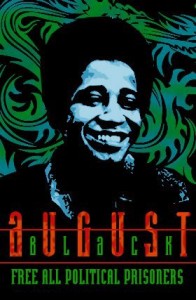

An enemy bullet has once more brought grief and sadness to black people and to all who oppose racism and injustice and who love and fight for freedom. On Saturday, August 21, a San Quentin guard’s sniper bullet executed George Jackson and wiped out that last modicum of freedom with which he had persevered and resisted so fiercely for eleven years.

An enemy bullet has once more brought grief and sadness to black people and to all who oppose racism and injustice and who love and fight for freedom. On Saturday, August 21, a San Quentin guard’s sniper bullet executed George Jackson and wiped out that last modicum of freedom with which he had persevered and resisted so fiercely for eleven years.