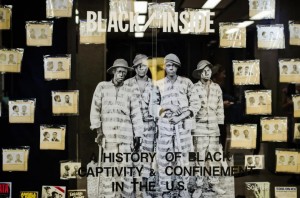

This weekend, I led a bus tour of various Chicago landmarks central to the history of black confinement and captivity. The group included youth and adults and I think that everyone learned something new. I will run the tour one more time on Saturday.

As I planned the tour along with the Black/Inside exhibition, I was reminded again about the overlooked chapters of black history. As I was doing my research, I learned of an episode that took place in 1850 in Chicago after Congress passed the Compromise of 1850 and its provisional bill, the Fugitive Slave Act (FSA).

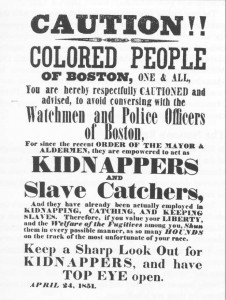

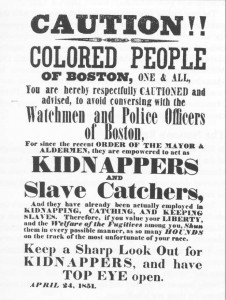

The Fugitive Slave Act denied runaway slaves the right to a trial by jury, authorized federal marshals to call upon bystanders to help them capture suspected fugitives, and imposed stiff fines and imprisonment on any citizen who aided escaped slaves or prevented their capture. Antislavery forces (mainly the Abolitionists) in the North declared the law to be unconstitutional. The law was intended to curtail the Underground Railroad. It had the opposite effect instead galvanizing resistance across the country. For example, abolitionists across the North printed posters warning black people that they were in danger.

The Fugitive Slave Act denied runaway slaves the right to a trial by jury, authorized federal marshals to call upon bystanders to help them capture suspected fugitives, and imposed stiff fines and imprisonment on any citizen who aided escaped slaves or prevented their capture. Antislavery forces (mainly the Abolitionists) in the North declared the law to be unconstitutional. The law was intended to curtail the Underground Railroad. It had the opposite effect instead galvanizing resistance across the country. For example, abolitionists across the North printed posters warning black people that they were in danger.

In Chicago, the response to the law was swift and dramatic. On September 30, 1850, more than three hundred black Chicagoans gathered at Quinn Chapel, the first black church in Chicago, located on the east side of Wells Street near Washington Street, to protest the Fugitive Slave Act. At the time, the city’s population was about 23,000 people (with only 378 blacks).

John Jones, a free black abolitionist and a leading figure of Chicago’s black community, rose to address the crowd. He read a series of resolutions conceived by himself and fellow black abolitionists, Henry O. Wagoner and William Johnson. Jones spoke out at the gathering:

We who have tasted freedom are ready to exclaim with Patrick Henry, “Give us liberty or give us death”… [and] in the language of George Washington. “Resistance to tyrants is obedience to God.” We will stand by our liberty at the expense of our lives and will not consent to be taken into slavery or permit our brethren to be taken.

To protect its members from “being borne back to bondage,” the group created a vigilance committee consisting of a black police force of seven divisions; each division had six persons who were to patrol the city each night to watch for slave catchers. The group also formed a correspondence committee, modeled on that of the American Revolution, called the Liberty Association, “for the general dissemination of the principals of Human Freedom.”

The committee’s resolutions reveal how Chicago’s black abolitionists viewed themselves and their fellow African-Americans: as a free people, heirs to the rights won by the American Revolution, ready to sacrifice their lives, if necessary, to maintain that freedom. This view of African Americans as rightful citizens of the Republic was central to the abolitionist movement of the mid-nineteenth century and key to understanding the actions of those in Chicago and elsewhere who worked to end slavery.

On October 21, the Chicago Common Council (now called the City Council) formally denounced the Fugitive Slave Act as unconstitutional and nonbinding. By a vote of nine to two, the council resolved that the “Senators and Representatives in Congress from the free States who aided and assisted in the passage of this infamous law…are only to be ranked with the traitors Benedict Arnold and Judas Iscariot.” It also resolved that it would not require the police to assist in the arrest of fugitive slaves. John Jones and the other black people who had resisted the Fugitive Slave Act in Chicago had won something significant.