Clyde Kennard, Political Prisoner: Victim of Another Kind of School-to-Prison Pipeline

Every day is Black History day on the Prison Culture blog. But I do want to acknowledge February as Black History Month. Unlike others, I am not ambivalent about the month. I think that it is a good thing that we have it and I acknowledge that it took over 100 years of work by scholars like Carter G. Woodson among others to make it a reality. I am one of the beneficiaries of that hard work, organizing, and scholarship. I am grateful. I’ve settled on Thursdays as my regular day for posting something related to the history of the PIC on the blog. I will of course continue to weave historical moments in other posts but you can always be assured of finding something history-related on Thursdays here.

“That there was no simple crime with one indictable perpetrator makes it all the more universal.” – Ron Hollander

There once lived a man. He was a very good man. If he were alive today, Tom Brokaw would be touting him as one of the “Greatest Generation.” His name was Clyde Kennard and he was killed by the state. His story has been called by historian John Dittmer “the saddest of the whole [Civil Rights] Movement.”

There once lived a man. He was a very good man. If he were alive today, Tom Brokaw would be touting him as one of the “Greatest Generation.” His name was Clyde Kennard and he was killed by the state. His story has been called by historian John Dittmer “the saddest of the whole [Civil Rights] Movement.”

Mr. Kennard is not a household name even among those who know a lot about the Black Freedom Movement. He should be. I only learned about Clyde Kennard’s story in 2000 when I read David Oshinsky’s “Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm, & the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice.” I then heard more about the case in 2006 when the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University Law School won his posthumous exoneration with the help of three local high school students: Mona Ghadiri, Agnes Mazur and Callie McCune.

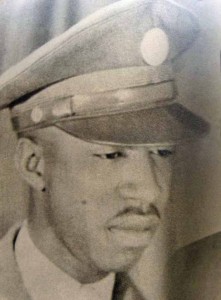

Born in Hattiesburg Mississippi in 1927, Kennard was according to all who knew him quiet and smart. At 12, he moved to Chicago and at 18 he joined the Army where he spent 7 years as a paratrooper. He served in Germany and in Korea. After he was honorably discharged from the Army, he used some of his savings to buy a chicken farm for his parents in Hattiesburg. In 1952, Clyde moved back to Chicago and enrolled in the University of Chicago.

After three years at U of C, his stepfather died. Clyde decided to move back to Mississippi to help his mother with the chicken farm. Because he had already finished three years of his political science degree requirements, he decided that he would enroll at Mississippi Southern College (now called University of Southern Mississippi) to complete his studies.

Unfortunately for Clyde, Mississippi was virulently opposed to integrated education. Mississippi Southern had not admitted any black students as of 1955 when Clyde tried to apply. The state was so opposed to admitting blacks to its Universities that it set up a Sovereignty Commission with the expressed mission of resisting outside efforts to impose integration on the State’s education system.

Unfortunately for Clyde, Mississippi was virulently opposed to integrated education. Mississippi Southern had not admitted any black students as of 1955 when Clyde tried to apply. The state was so opposed to admitting blacks to its Universities that it set up a Sovereignty Commission with the expressed mission of resisting outside efforts to impose integration on the State’s education system.

When Kennard applied in 1955, he was rejected. He was asked to provide five character references from alumni who had attended Mississippi Southern and who lived in his county. There was absolutely no way that a black man living in Hattiesburg would be able to find five white people to offer a recommendation for admission to the University. Everyone knew this. It was basically the equivalent of a poll tax but for education. Kennard was persistent though. He asked Mississippi Southern for a list of white alumni in his county but was told that there was no such list.

In 1958, Clyde Kennard took to the pages of the local paper where he penned a letter announcing his intention to enroll in the University the following term in January. The Sovereignty Commission quickly got to work to figure out how to prevent this. One member of the Commission (who was also affiliated with the local White Citizens’ Council), openly discussed assassinating Kennard to prevent him from attending Mississippi Southern. This document from the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission (December 17, 1958) shows that Kennard was branded as an “integration agitator.” He had in fact been, according to Civil Rights veteran Joyce Ladner, the President of the Hattiesburg, Mississippi NAACP Youth Council in 1958. He was indeed an activist for civil rights but he was acting on his own in his quest to continue his education.

Because he refused to back down and withdraw his application to attend the University, the Sovereignty Commission tried to destroy Kennard first by launching extensive investigations into all aspects of his life. They came up empty. Then they tried to get prominent local black leaders to convince Kennard to drop his quest for admission to the University. This didn’t work either. They tried to foreclose on his farm. No dice.

When these efforts were unsuccessful, they framed him twice for crimes that he didn’t actually commit. They first arrested him for illegal possession of alcohol and reckless driving. Everyone who knew Clyde knew that he never drank. He was found guilty but the conviction would eventually be thrown out of court when it was shown that the liquor had been planted in his car by the FBI. Jesse Bass describes what happened in his second case:

In November 1960, The jury only deliberated for 10 minutes before returning its guilty verdict. Clyde Kennard was sent to Parchman Farm & it became a death sentence. I have written at least a couple of times about Parchman & its brutality. You can read those posts here and here.The next year, 19-year-old Johhny Roberts received a conviction and suspended sentence from the Forrest County Circuit Court for stealing $25 of chicken feed from the same cooperative that foreclosed Kennard’s farm. Roberts testified that Kennard bought the feed from him and had knowledge it was stolen.

An all-white jury convicted Kennard of accessory to burglary based on Roberts’ testimony and judge Stanton A. Hall sentenced him to seven years hard labor, one year for each $3.57 worth of stolen feed. The Mississippi Supreme court agreed, and the Federal Supreme Court denied an appeal.

David Oshinsky (1998) describes Kennard’s time at Parchman:

Kennard did common labor at the prison, working the “long line” in the fields. At night, he wrote letters home for illiterate convicts and taught a number of them to read and write. In 1962, suffering from severe stomach pains, Kennard was moved to a Jackson hospital, where surgeons removed a cancerous growth from his colon. He returned to Parchman eleven days later, despite a medical report that recommended immediate parole “because of the extremely poor prognosis in this rather young patient.” Sent back to the fields, Kennard lost forty pounds and could barely walk. Yet Parchman officials cancelled his medical checkups, claiming he did not need additional care (p.232).

Larry Still, a reporter for JET Magazine, published an article about Kennard that appeared in January 1963. The publicity from the article brought the Kennard case to the attention of many Northern activists including Dick Gregory & Dr. King.

Civil Rights activists in Mississippi & across the South (including Medgar & Myrlie Evers, Joyce & Dorie Ladner, Vernon Dahmer, among others) had already been mobilizing on behalf of Clyde Kennard. Thurgood Marshall took Kennard’s conviction to the Supreme Court in an unsuccessful attempt to overturn it.

Finally in February of 1963, Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett, who was sick of negative media scrutiny, agreed to release Kennard who was close to death at this point. Supporters got him to Chicago where he died on July 4, 1963 at the age of 36 years old. Myrlie Evers wrote that Kennard was “a victim more of Mississippi justice than the cancer that caused his death.”

To get a sense of who Kennard was as a person, read the following paragraph by Minchin and Salmond (2009):

Even when he was close to death, Kennard remained dignified and upbeat. When he was released from prison in February, for instance, he refused to criticize his captors but instead expressed his desire to return to his chicken farm and help his mother. Too weak to work the farm, Kennard instead underwent emergency surgery in Chicago but his cancer continued to spread. As his condition deteriorated, the committed Christian again refused to blame his persecutors. “I still think there are a few white people of good will in this state and we have to do something to bring this out,” he declared. At this time Kennard also spoke of using whatever time he had left to keep fighting for racial justice in Mississippi (p.218)

John Howard Griffin (author of Black Like Me) visited Kennard in the summer of 1963 and wrote an account of it. He recounted some of Kennard’s last words including these about his ordeal:

“I’d be glad it happened if only it would show this country where racism finally leads,” and “Be sure and tell them what happened to me isn’t as bad as what happened to the guard, (who verbally abused him on the ride to the doctor) because this system has turned him into a beast, and it will turn his children into beasts.”

In later years Johnny Roberts recanted his testimony but it was too late for Kennard by then. He told reporter Jerry Mitchell that:

Kennard had “nothing to do with stealing the chicken feed” and that he had been arrested “not because of the feed but because he was trying to go to Southern.” [Minchin and Salmond, 2009]

Larry Still begins his January 1963 article about Clyde Kennard with the following words:

“Among the grim integration jokes being told about Mississippi there is the legend that students who wanted equal high school education were sent to jail and a Negro who wanted an equal college education in the state was sent to prison (p.20).”

Clyde Kennard died because he was desperate to get a college education. As we talk about today’s school-to-prison pipeline, let us not forget that for decades black youth and adults were victims of another kind of school-to-prison pipeline. This is not a new phenomenon, unfortunately. It would behoove us to lift up these historical moments for today’s youth. Kennard paved the way for the more famous James Meredith and others who came after to integrate the schools and Universities of Mississippi. We should call out his name alongside those of King, Malcolm, Stokely, Huey, Ella, Fannie, Septima and more…

To learn much more about Clyde A. Kennard’s life, you should read this good essay by Timothy J Minchin and John A Salmond titled “The saddest story of the whole movement: The Clyde Kennard case and the Search for Racial Reconciliation in Mississippi 1955-2007″ (PDF). The following is an article (PDF) about the three high school students who were involved in the successful campaign to posthumously exonerate Mr. Kennard. The Mississippi Archives have amazing primary source documents from the Sovereignty Commission about Clyde Kennard. You only need to type in his name to access them. Finally, here is a paper about how the media covered the Kennard case.