No Country For Black Boys: Trayvon Martin, Cages, & Rage…

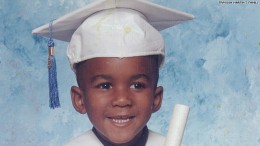

It’s been a year since the killing of Trayvon Martin. I’ve written a lot about the case on this blog. Yet I’ve not really written about Trayvon as a person. I’ve only considered him as a symbol. He has been a proxy to allow me to discuss issues like the criminalization of black youth for example. In fairness, I didn’t know him personally and still know almost nothing about him. I have caught snippets of his biography listening to the pained words of his parents and his brother. I have also heard about who he supposedly was from the right wing media and other outlets that have tried to portray him as a hoodlum: a weed smoking, school failing, tatooed, gold teeth wearing black gangster wannabe. Those images circulate in the public sphere.

Trayvon was 17 years old when he was gunned down in his father’s gated community. I’ve often imagined him lying like a chalk figure on cold, wet concrete gasping for breath. I admit that his face is sometimes replaced in my head by those of other young men I’ve known over the years who are either incarcerated, dead, or disappeared. In order to remain sane, I try not to dwell on these thoughts.

About a month ago, I heard from one of my favorite young people that his 19 year old cousin was gunned down in cold blood on 84th street. This had happened just three weeks before we saw each other. I wasn’t shocked by this. Death announcements are routine now.

The young man then uttered words that I’ve been hearing a lot in the past few years.

“I’m just tryin’ to get my head right,” he said. “I’m just tryin’ to get my head right,” he repeated.

This phrase has become a euphemism and it is heartbreaking. For the young black men in my life, “getting your head right” doesn’t mean talking about feelings. On the contrary, it is code for choking down your emotions; swallowing your sorrow when it threatens to overwhelm. The sadness stays lodged in the pit of your stomach & you don’t dare express your sense of profound pain. This is a rational coping mechanism but I think that it is unhealthy and can sometimes even be deadly. But this is life in what the young men in my world call “Chiraq.” [I’m not ready to unpack the meaning of this word yet.]

There is rage that is always close to the surface for black boys in Chicago. It can and does explode. Lookman is a young black man who I know and respect. He is part of a leadership development program that my organization incubates called Circles and Ciphers. Listen as he shares his experience of getting into fights at school which eventually landed him behind bars at the young age of 15.

When Lookman talks about his time in the “Audy Home,” he means the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center (JTDC). Below is a photo of a cell at the juvenile jail. Lookman talks in the audio clip about looking out of the window in order to feel “human again,” you can see what that window looks like.

In Chiraq, we lock black boys up to cage the rage but it doesn’t disappear, it only grows. To heal the walking wounded, we cling to anything that we can find. We beg them to talk, to express, to let go. We have almost no resources. The state is allocating those to the military and to build more cages. Some of them like Lookman channel their feelings in spoken word. “I’m tired,” he says.

Once the words begin to flow, they keep coming…

Savon never speaks. The rage is there. He never speaks. Then one day in a makeshift recording studio, he shares part of his life story while everyone holds their breath.

If you listen closely to the young men’s words, you can hear a tiny bit of ice cracking. Some of the rage trapped underneath is slowly dissipating. I am not naive though. There are too many who need spaces for healing but can’t find them. There are too many who need jobs that aren’t there. There are so many who we’ve disregarded, thrown away like garbage. So many…

A long time ago, I knew a boy. He told me that there was no place for him in this society. He used to talk with me a lot about moving to Africa. He knew that I had family there. I told him that he was welcome to visit any time. That he would be received like long lost family by my kin. But we both knew that he would never visit the Continent. It became a game between us. Every time I saw him I would ask if he was packed for his trip yet. He would smile and say that he was “working on it.” He made it to Florida where he was shot and killed in 2007. I heard the news from his former girlfriend who was a young woman I worked with for several years. So he never did make it to Africa and I’ve sometimes wondered if he would still be alive today if he had made the trip. The sad truth stares me in the face: the United States may be no country for black boys…