“We Are Not Criminals:” Immigration Reformers in a Box

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been having a Facebook conversation with my friend Rozalinda about the “comprehensive immigration reform (CIR)” bill. It began organically and is informal. It’s intended to be a bit of a stream of consciousness conversation of the sort folks used to have in the French salons of old (but hopefully less pretentious :)).

Rozalinda has archived our conversation here. For those interested in immigration issues and in the carceral state, I invite you to read Rozalinda’s thoughts in particular, she is really brilliant and visionary. Today, I’ve decided to share my latest Facebook note. Both Rozalinda and I invite others to join in the conversation. Feel free to leave comments, ideas, and thoughts at the blog. The more the merrier…

Dear Rozalinda,

It’s taken a few days to respond because as you know I am always swamped with work.

As I’ve been slowly making my way through this “immigration bill,” I have of course noticed that it explicitly excludes people with criminal convictions (of various kinds). Frankly, I understand why it would be framed in this way. I am assuming that the bill’s writers think that this will make it more palatable to certain constituencies. It ensures that only the so-called “deserving” will have access to this potential “gift” of status normalization and citizenship.

The focus on excluding “criminals” has been the part of the bill that has absorbed most of my attention and interest. I want to address myself to some of the points that you raise about immigrant detention and deportations. Writing on the Al-Jazeera blog, Beth Caldwell offers some useful historical context about the uses and purpose of deportation:

“Deportation has a long track record as a tool used to rid societies of people deemed socially undesirable, and excluding those with criminal convictions from immigration reform is consistent with its historic use. Political theorist William Walters traces the origin of modern deportation to political banishment employed by ancient Greece and Rome, the expulsion of poor or religiously unpopular groups during the Middle Ages in Europe, and the forced movement and genocidal practices of Nazi Germany.

Walters argues that during the late 19th century and early 20th century “states increasingly used deportation as a way of governing the welfare of their populations, both by excluding the socially ‘undesirable’ (paupers, prostitutes, anarchists, criminals, the insane, excludable races, etc) and by removing foreign labour… during periods of economic recession”.

The emergence of the term “criminal alien”, designed to both demonise and alienate, exemplifies the relationship between American immigration policy and social cleansing.”

Interestingly within the immigration advocacy community, deportation as a concept is almost never troubled. It is taken as a given that we must deport people. Here’s a quote from a press release announcing a new report that was published by Human Rights Watch:

“The US government is turning migrants into criminals by prosecuting many who could just be deported,” said Grace Meng, US researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. “Many of these migrants aren’t threats to public safety, but people trying to be with their families.”

So advocates are explicitly conceding that some migrants can and should “just be deported” rather than prosecuted for their “crime” of living without documentation in the country. It’s a major concession in my opinion and buys into the framing of the state.

While the current “CIR” bill moves through the Senate, the Department of Homeland Security budget appropriation bill is also being debated on a parallel track. I was particularly interested to read a couple of days ago that Texas Congressman John Culberson “secured language in the [appropriation] bill that requires Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to use all vacant public and private sector detention facilities to house the detained illegal alien population. ICE will no longer be able to claim it does not have the space to lock up illegal aliens, thereby preventing them from arresting and detaining them.”

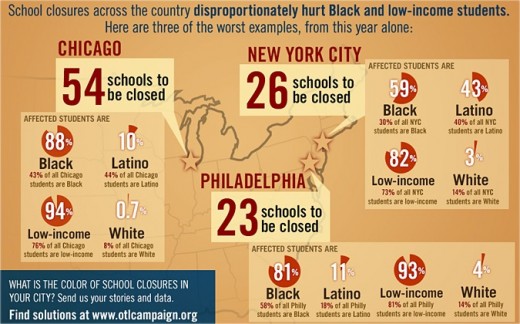

So as the Congress works to supposedly “reform” the immigration system on the one hand, on the other it is preparing for the jailing and incarceration of more people. This is something that is basically happening out of the view of most Americans. In addition, the current Senate gang of eight bill includes provisions suggesting that borders must be certified to be “secured” before the “path to citizenship” can officially open for millions of undocumented people. This means that deportations MUST necessarily continue in order for the promised “path to citizenship” to open. What kind of Faustian bargain is this?

While the political rhetoric focuses on deporting “dangerous criminals,” according to ICE’s own statistics in 2012 nearly 35% of the people kicked out of the country had drug or alcohol convictions. The “dangerous criminal” formulation is of course a canard. But it’s an effective one because it is shorthand in this country for those who can be disposed of and those who should be demonized & discounted.

Here’s the problem [as I see it] in addressing this aspect of CIR, we haven’t done a good job opening up the space for discussions about prison abolition in the broader culture. This therefore greatly constrains our ability to have transgressive conversations about ideas such as “criminal aliens” within the context of CIR. Here’s an example of what I mean. While prisons are places where we warehouse people to punish them in this country, they also do the ideological work of isolating and disappearing undesirable populations in the name of “rehabilitating them” and protecting the “good” citizens. This is very important to remember as we talk about immigrants who are always categorized as desirable or not. The rhetoric in the “immigration bill” and more importantly in discussions about the bill suggests that we don’t want to criminalize” and lock up the “good immigrants.” This bill institutionalizes these distinctions and creates new ones. As such, a lot of work has to be done by advocates to prove that immigrants are in fact “good.” It’s a trap and one wonders if advocates are inevitably doomed to fall into it.

The irony of all of this is that the carceral state is deeply invested in circulating “conversion stories” about the “reformed criminal.” Rehabilitation is supposed to be a central tenet of the American prison system. Prisoners themselves often adopt this rhetoric in their writing and in their speeches. They talk about prison being ‘the best thing’ that ever happened to them. They talk about being ‘changed’ or ‘transformed.’ This language and these ideas are embedded and reified within the culture at large. It’s a story that everyone knows. It explains the popularity of films like the Shawshank Redemption.

But interestingly, CIR offers no possibility of a “conversion story” for an immigrant who has been criminalized. That person is automatically disqualified from a quest for citizenship. The immigrant who is criminalized is forever a ‘criminal’ and will be precluded from ever gaining citizenship rights. Why can’t the immigrant be ‘rehabilitated?’ What does this mean about what the country actually believes about the possibilities of so-called ‘rehabilitation’ for ‘criminals?’ How can we use this seeming contradiction as the basis for calling for prison abolition? If the prison is abolished, will we also be rid of the concept of ‘rehabilitation?’ Does this then afford us an opportunity to get outside of the constraints of the concept of “criminality?” These questions are, I think, deserving of more consideration. Without answers though, I think that this leaves immigration reformers in a box that they cannot escape. I want to think more about this box and what it keeps contained when I have a chance…

In the meantime, I’ll give Beth Caldwell [who I cited earlier] the final word:

“The immigration bill currently pending in the US Senate further exacerbates the demonisation of immigrants – primarily Latino and black – who have gotten into trouble with the law. In doing so, the bill falls short of its stated purpose of being “comprehensive” in its effort to reform immigration law. It fails to address some of the most problematic aspects of contemporary American immigration law, including the forced separation of American families.”