Guest Post: “Unpacking Chiraq 2: Repression, RICO, and War on Terror Tactics” by Nancy A. Heitzeg

Unpacking “Chiraq” #2: Repression, RICO, and War on Terror Tactics

by nancy a heitzeg

What does it mean to call a city a War Zone? To write entire Black and Brown neighborhoods – and all their inhabitants – out of the United States of America and into a script that so effectively “others” them that they are now a foreign enemy state? What does it mean for public perception? What does it mean for police state response?

While the term “Chiraq” may have one set of meanings for those who survive Chicago’s high gun violence rate (see Unpacking ‘Chiraq’ #1: Chief Keef, Badges of Honor, and Capitalism), it serves to legitimate, without question, already solidified stereotypes of youth of color. “Chiraq” also links, per usual this violence to gangs. “Chiraq” implies that the already draconian domestic police approach to gangs is insufficient, and that a military response is now needed.

What other message could one take from the recent edition of HBO’s Vice Episode #9 Chiraq ? Where segments of a major US city are described like this — “The South Side of Chicago is basically a failed state within the borders of the U.S.”? Where viewers are blithely taken from Chicago’s Southside to then “hunting oil pirates in Nigeria”?

The lethal combination of gangs and guns has turned Chicago into a war zone. To see why the Windy City, now dubbed “Chiraq,” had the country’s highest homicide rate in 2012, VICE visits Chicago’s most dangerous areas, where handguns are plentiful and the police and community leaders are fighting a losing battle against gang violence. In the neighborhood of Englewood, we patrol with police, visit with religious leaders, and hang out with members of gangs – soldiers in a turf war that has spread into new communities as projects are destroyed and residents are forced to move elsewhere.

Assata Shakur: Prisoner in the United States (An Interview – Part 2)

Part 1 of the interview is here.

Q: Could you tell us exactly what happened when you first went to court in your first trial? What were the charges that were brought against you and exactly how did the state deal with prosecuting you in this particular case?

AS: The first trial that I participated in was the New Jersey trial. They put in a whole lot of other charges like armed robbery – I was supposed to have robbed the police of guns – and then assault, and whole list of charges. But the main charges were murder of a New Jersey state policeman and wounding another one. We were on trial, we were in the jury selecting process.

Q: When you say “we,” could you state exactly who –

AS: Sundiata Acoli and I were on trial together. We had the same charges and we decided that we would go on trial together. They didn’t oppose that.

Q: Had you recovered from your wounds at the time?

AS: I was still wearing a brace for the broken clavicle, but the problem was mainly my right arm. I was basically paralyzed. And I was a wreck. I’d broken out in a rash, I was very thin… Anyway, we started the jury selection process. And in the middle of it the trial was stopped. It was postponed until January, 1974.

Q: Why?

AS: Because it was found out that there was such a racist climate in the jury room that the trial could no longer proceed. There was like this lynch mob atmosphere, there was no way we could receive anything resembling a fair trial. So they gave us a change of venue to another county – Morris County – where we were supposed to resume the trial. Morris County happened to be 99% white and one of the richest counties in the state of New Jersey, as a matter of fact, in the whole country.

Q: What evidence was presented to indicate that there was a racist climate at that time?

AS: There was no evidence presented, but the press had been trying me for years. I was turned into a monster. They pictured this vicious woman that goes around terrorizing police, this madwoman essentially… They had created this whole mythology in order to destroy me. They started this whole mythology in order to destroy me. They started building this whole campaign in the press in 1970-71. The press were free to say anything and the police, the FBI, the CIA were the ones who were feeding the press information. No one ever asked me any questions and even attempted to deal with the fact that we were human beings, people who had a long history of struggle. It was just overwhelming, and people believed that.

Q: You notice that there was a correlation between the information the police had in their possession and the information and the distortions in the press?

AS: It wasn’t information. They just fabricated things, and fed them to the press. They would accuse me of having I don’t know how many pending charges, and none of that was true. Anybody reading the paper would think that we had been convicted of committing so many crimes all around the country and never was there a mention that we’d never been found guilty of any crime.

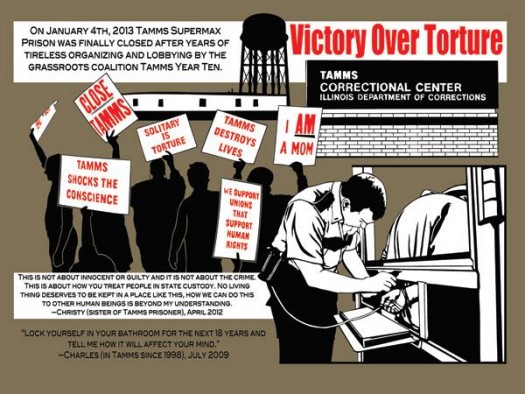

Image of the Day: Closing TAMMS…

I’ve written a lot about the TAMMS Year Ten Campaign on this blog. It’s because I have such admiration for my friends and allies who were involved in the (more than) decade long struggle to close that torture chamber. Anyway, artist Paul Kjelland has created a poster to celebrate the closing of TAMMS Supermax prison. You should read his description of the process for creating the poster.

Assata Shakur: Prisoner in the United States (An Interview – Part 1)

This is the testimony of Assata Shakur, formerly JoAnne Chesimard, who was arrested on the evening of May 2, 1973, along with Sundiata Acoli and Zayd Malik Shakur (who was killed by the New Jersey state police). Assata Shakur, who is now in exile, in Cuba, was a member of the Black Panther Party and of the Black Liberation Army. Here she gives testimony regarding her treatment after being captured by New Jersey state troopers. [Source: Still Black, Still Strong: Survivors of the War against Black Revolutionaries. Edited by Jim Fletcher, Tanaquil Jones and Sylvere Latringer (2003)]

Prisoner in the United States (This is only part of the interview, part 2 will be published on Monday)

Assata Shakur: On the night of May 2, I was shot twice by the New Jersey State Police. I was kept on the floor, kicked, pulled, dragged along by my hair. Finally, I was put into an ambulance, but the police would not let the ambulance leave. They kept asking the ambulance attendant: “Is she dead yet? Is she dead yet?” Finally, when it was clear that I wasn’t going to die in the next five or ten minutes, they took me to the hospital. The police were jumping on me, beating me, choking me, doing everything that they could possibly do as soon as the doctors or the nurses would go outside. I was half dead – hospital authorities had brought in a priest to give me the last rites – but the police would not stop torturing me. That went on until the next morning, when I was taken to the intensive care unit. They had to calm down a little while I was there. Then they moved me to another room, which was the Johnson Suite, and they closed off the exit from the hallway. So they could virtually control all traffic in and out. It was just open season on me for about three or four days. They’d turned up the air conditioning so that I was freezing to death. My lungs were threatening to collapse. They were doing everything so that I would get pneumonia.

Q: Did the medical staff participate or acquiesce to this treatment while you were under their care?

AS: Some of them did. The first night there was a doctor who was just as bad as the state troopers. He said: “Why did you shoot the trooper?” – He didn’t know if I had done it or not, but he just jumped on me. Some of the nurses were very supportive; they could really see the viciousness of the police. One of them gave me a call button, so that I could call whenever the state troopers came in my bed. That way I was able to avoid being further beaten up. They had my legs cuffed to the bed, even though I was half dead and my leg was swollen. Some of the nurses protested the way they had my foot cuffed. It was really bleeding and sticking in the flesh.

Prison Architecture #5

the murdered and the mourned…

“I should write something to mark the beginning of the George Zimmerman trial” is the thought rattling through my mind incessantly over the past couple of days. But I fear that I have run out of words… I’ve written about both Zimmerman and Trayvon Martin many times on this blog. No more words are forthcoming. I’ve been doing my best to ignore Sybrina Fulton’s daily tweets about her son this week. Today, she wrote: “You don’t have to know me to know my pain, use my pain & my lost to stand up for something.” It pushed me over the edge and I felt compelled to call forth Trayvon’s spirit.

“the mysterious connection

between whom we murder

and whom we mourn… – Audre Lorde (Dear Joe)”

I’ve been preoccupied with thoughts about his soul but also our country’s collective one. Does Trayvon’s soul rest easy? Or is it caught in the space “between whom we murder and whom we mourn” like thousands of other black people who have been tragically killed over the years in this country? Audre Lorde has written that: “Our dead line our dreams…” Unfortunately, too often black children are more likely to embody this country’s fears and nightmares.

Across time and space, my mind travels to Baton Rouge, Louisiana in December 1912. Simon Cadors, a black man, is convicted of killing a rich white planter. He’s sentenced to hang. As he awaits his appeal, he is kidnapped from his jail cell by a white mob and lynched. His body is found hanging from a telegraph pole on Christmas eve. Around his neck is a placard that reads: “The inevitable penalty.” It’s a warning to every black person in Louisiana; it’s southern ‘justice.’

A hundred years later, in my mind’s eye I see Trayvon. He’s lying on the cold concrete. As I get closer, I notice a placard hanging from his neck that reads: “The inevitable penalty.” It’s a warning to every black person in Florida; it’s southern ‘justice.’

There is a continuity between Simon Cadors and Trayvon Martin. Both exist in the space “between whom we murder and whom we mourn.” Despair and hope are once again at war within me. Audre whispers in my ear: “Despair is a tool for your enemies.” I decide to search for signs of hope. I find it once again in the voice of our youth:

I tell ’em listen

I don’t fit your description

I don’t think that I embody this picture that you all are depicting

Lamar Jorden is a Chicago poet, writer and rapper. He has been part of the Louder than a Bomb (LTAB) poetry festival and appears on this year’s LTAB Mixtape. His song “Listen” is an exhortation for his peers to define themselves and to reject the negative stereotypes that society imposes on them. Jorden has taken on Sybrina’s Fulton’s call to use our pain and to stand up for something. He is also concerned with questions that Audre asked in 1977 (many years before he was born): “In what way can we cease to contribute to our own oppression? What hidden assumptions of the enemy have we eaten and made our own?” These are questions worth wrestling with as we work to build the world that we want to live in; a world free of oppression where true justice is possible.

Poem of the Day: We Real by Kevin Coval…

I featured a poem titled “Chicago (Keef)” by Kevin Coval last year. It is from his chapbook “More Shit Chief Keef Don’t Like.” Today, I’m featuring another poem from the collection. It’s called “We Real” and is inspired by one of my favorite poets (of all time) Gwendolyn Brooks.

WE REAL

The Glory Boys on house arrest

we real. we

steel. we

still here. we

no fear. we

know school lame. we

dope game. we

know gangs. we

Jeff Forte kids. we

jail birds. we

broke, bitch. we

capitalists. we

jupiter gassed. we

murdered fast. we

unseen we

wanting we

something we

more than one thing. we

eastside. we

southside. we

westside. we

on the block, we

high noon. you ravinia picnic and air condition. we

fire hydrant & fire, cracker. we

hot hell in June. you nap noon. you spoon. we

rap. we

die, soon

On (Some) Black People and the Surveillance State…

[This is a work-in-progress. I am puzzling through my thoughts on these matters. Feel free to leave your comments and ideas]

Some black folks in my life have no patience for some white people’s new found interest/discovery of Cointelpro and particularly of their (now incessant) invocation of the FBI’s surveillance of Martin Luther King Jr. The interest seems to them instrumental and transactional. It’s as if folks who have had little concern about black people’s daily experiences of state violence are now demanding our support in safeguarding their rights. There has been no prior relationship or trust-building so some black folks are feeling used and exploited. It brings to mind the lyric: “Will you still love me, tomorrow?” This sentiment is understandable.

As the revelations about NSA surveillance roil the political world, media outlets & others are suddenly very interested in Americans’ views on matters of privacy, civil liberties, and individual rights. A poll was released a few days ago. It apparently found that “blacks were more likely than whites and hispanics to consider the patriot act a necessary tool [that helps the government find terrorists] (58% to 42% and 40% respectively). On my Twitter timeline, several people mused about why this would be the case. After all, black people are the disproportionate targets of government surveillance at all levels (city, county, state, and federal). We’ve always been under the gaze of the state and we know that our rights are routinely violable. Moreover, we are used to these abuses being ignored by the majority of our fellow citizens. Shouldn’t black people then be the most opposed to violations of civil liberties and to laws that encroach on those liberties?

The Drug War: Still Racist and Failed #19

I came of age in New York City during the height of the crack cocaine era. I don’t think that young people living in the city today can fully comprehend what this was like. One thing to say is that the media was guilty of reporting countless sensational stories about crime and violence during that time. Many of these stories included a myriad references to “crack babies.” Turns out that there was no actual epidemic of “crack babies.” It served as another excuse to wage war on black women and our bodies in particular…

The New York Times reported recently on the “epidemic that was not:”

This week’s Retro Report video on “crack babies” (infants born to addicted mothers) lays out how limited scientific studies in the 1980s led to predictions that a generation of children would be damaged for life. Those predictions turned out to be wrong. This supposed epidemic — one television reporter talks of a 500 percent increase in damaged babies — was kicked off by a study of just 23 infants that the lead researcher now says was blown out of proportion. And the shocking symptoms — like tremors and low birth weight — are not particular to cocaine-exposed babies, pediatric researchers say; they can be seen in many premature newborns.

The worrisome extrapolations made by researchers — including the one who first published disturbing findings about prenatal cocaine use — were only part of the problem. Major newspapers and magazines, including Rolling Stone, Newsweek, The Washington Post and The New York Times, ran articles and columns that went beyond the research. Network TV stars of that era, including Tom Brokaw, Peter Jennings and Dan Rather, also bear responsibility for broadcasting uncritical reports.

Included in their report is a very well done video. You can watch it here.