Herman Wallace… We Speak Your Name & Those of the Ancestors

Herman Wallace would have turned 72 years old today. Instead on October 4th, he died in his sleep, his body ravaged by liver cancer. Wallace had just been released from a Louisiana prison three days earlier after having spent over 40 years in solitary confinement in a 6 by 9 cell.

Among his final words, he is reported to have said: “I am free. I am free.” It’s a minor miracle that he was able to die surrounded by friends instead of in a prison hospital. A judge overturned his 1974 conviction for the murder of a guard at Angola prison and ordered his immediate release. Only a couple of days later, while he lay dying in his hospital bed, the state of Louisiana filed charges to re-indict him. There was actually a question as to whether he might be re-arrested. Louisiana was determined that Wallace should die in prison by any means necessary.

Yesterday, Wallace was buried and I’ve been thinking again about the fact that some of his final words before dying were about being “free.” Is death the only way for black people to be “free?” As Wallace’s family continues to raise money to cover the expenses incurred by his funeral, one has to wonder if even death can liberate blackness from captivity.

Yesterday, Wallace was buried and I’ve been thinking again about the fact that some of his final words before dying were about being “free.” Is death the only way for black people to be “free?” As Wallace’s family continues to raise money to cover the expenses incurred by his funeral, one has to wonder if even death can liberate blackness from captivity.

This brings me to the story of Prince Mortimer who I have been thinking a lot about since hearing of Herman Wallace’s death. Mortimer died in 1834 in Wethersfield State Prison. He was 111 years old. Prince Mortimer arrived in America when he was 6 years old from Guinea in West Africa. He was enslaved in Middleton Connecticut and imprisoned at 87 years old for attempting to poison one of his masters, a man by the name of George Starr.

If not for a brief mention of him in an 1844 book by Richard Phelps titled “Newgate of Connecticut : its origin and early history,” Prince Mortimer’s story would have been lost to us. Instead, a lawyer turned writer named Denis R. Caron wrote a book about his life titled “A Century in Captivity: The Life and Trials of Prince Mortimer, a Connecticut Slave.” Frankly the book does a much better job at describing early American prison history than it does at painting a comprehensive picture of Mortimer’s life and of slavery. This is mostly because primary source material about Mortimer is almost non-existent. Regardless, it was through this book that I first learned of him.

When he was 103 years old, Mortimer was transferred from Newgate prison which was being permanently shuttered to Wethersfield State Prison. There, he spent his final days in solitary confinement in a 3 1/2 by 7 cell without water or heat. He was still expected to work even at his advanced age. When Prince Mortimer died in 1834, he was buried in the prisoners’ cemetery in an unmarked grave.

And so I’ve been thinking about Herman Wallace in his tiny cell for over 40 years and of Prince Mortimer who spent 105 years in captivity. I’ve been thinking about the connections between their lives 140 years apart. Mortimer died incarcerated in 1834 and Wallace was sentenced to life in prison in 1974. In the brief account about Mortimer in Phelps’ 1844 book, he writes:

“He appeared a harmless, clever old man, and as his age and infirmities rendered him a burden to his keepers, they frequently tried to induce him to quit the prison. Once he took his departure, and after rambling around in search of some one he formerly knew, like the aged prisoner released from the Bastille, he returned to the gates of the prison, and begged to be re-admitted to his dungeon home, and in prison ended his unhappy years.”

As an enslaved black man in America, Mortimer had been prepared for his prison existence. After all, he’d already spent 81 years in bondage & captivity before he set foot inside Newgate prison. Wallace also understood that as a black man, he had been born into a captive society in a state of confinement where his opportunities were curtailed. Yet, there was something in Wallace’s spirit that always refused to be caged. I’d like to think that perhaps Prince Mortimer was by his side whispering, “Hold on, son. Don’t let them break you.” Maybe Mortimer lived & died so that Herman Wallace could experience three days of freedom before his passing. My mother likes to say that as black people living today, we’ve already been paid for through our ancestors’ suffering. I don’t know if I agree. But I do know that Herman Wallace stands on the shoulders of Prince Mortimer. And that I stand on Wallace’s which means that I can see more of the horizon than either Mortimer or he could.

Prince Mortimer & Herman Wallace, I speak your names in the hope that those who will stand on my shoulders make it closer to true freedom.

I speak your names…

I speak your names…

I speak your names…

Rest in Power!

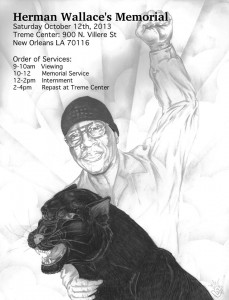

Herman Wallace is laid to rest in New Orleans surrounded by family, friends and fellow Black Panther members. 10/12/13 (photo by Giles Clarke).

Update: I am humbled and honored that this essay was featured in the Angola 3 Newsletter about Herman Wallace’s memorial.