I watched the excellent documentary “The Trials of Muhammad Ali” by director Bill Siegel a few weeks ago. When it comes to a theatre in your town or city, I highly recommend that you see it. Dave Zirin wrote a very good review of the film in the Nation Magazine. You should read it for a synopsis of the documentary.

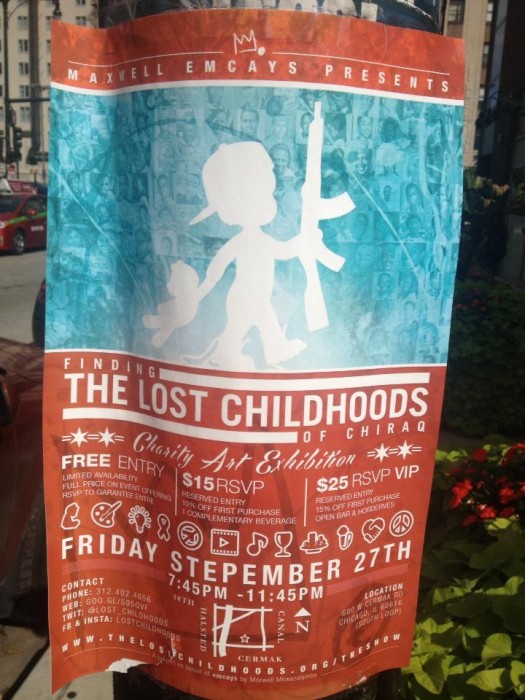

Muhammad Ali by Gordon Parks (1970)

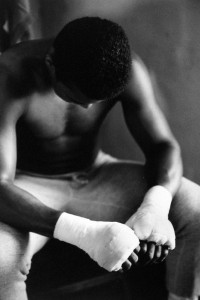

I’d like to address some larger issues that were raised for me as I watched the film. The documentary is mostly about young Ali. He is beautiful. His sense of humor and genial personality come across very clearly. The film covers new ground as it delves into Ali’s relationship with the Nation of Islam (NOI) and his court trials for refusing to join the military when he was drafted.

It’s easy to understand the appeal of the NOI to someone like Ali. The overt expression of racial pride evident in Black Muslim ideology and teachings was surely a draw. At a time when Black was not yet beautiful to find a community that affirmed your humanity and worth would have been and still is enticing. The emphasis on self-discipline and self-determination might have been an attraction as well for Ali, the athlete. Most importantly perhaps was Malcolm X who was the embodiment of confident black manhood for so many. So often, marginalized people are expected to define ourselves through negation. In other words, we are NOT lazy, we are NOT criminal. It’s much more difficult to self-define through a positive affirmation of our qualities. We ARE loving, we ARE resilient, we ARE human. Malcolm was a master at self-definition through positive affirmation and for this he was loved & respected.

As a black person watching the film and hearing Ali call out the people who he saw as his oppressors, I could feel pride and satisfaction at his truth-telling. Yet, I have to admit to wondering what white people watching the film are appreciating about the man. How are they able to absorb and reconcile his confident, unapologetic blackness? In America, blackness is usually punished and contained. As someone on Twitter with the handle @freshestmhizha mentioned, “Black culture is popular, black people are not.” So it can’t be Ali’s embodied blackness that white people are celebrating. What is it then?

The Ali of today is feeble and ill with Parkinson’s disease. There have been several false reports of his impending or actual death. In other words, Ali is not a threat to white supremacy anymore. This no doubt makes it easier for white audiences to countenance and ultimately to forgive Ali’s blackness. After all, they are aware that they are watching history from a safe distance.

When Ali was in his prime, he was clearly considered as a threat by the U.S. government (his FBI file will likely confirm this posthumously). He came to public attention in the 60s during a time when there was real fear within the government of a domestic black insurgency. Ali had to be neutralized and the government found its mechanism when he refused to serve in Vietnam saying that it was against his religious beliefs to participate in a war. Ali’s thoughts on his conscientious objection to military service are encapsulated in the following words (some of which we get to see and hear him speak in archival footage in the film):

“I ain’t draft dodging. I ain’t burning no flag. I ain’t running to Canada. I’m staying right here. You want to send me to jail? Fine, you go right ahead. I’ve been in jail for 400 years. I could be there for 4 or 5 more, but I ain’t going no 10,000 miles to help murder and kill other poor people. If I want to die, I’ll die right here, right now, fightin’ you, if I want to die. You my enemy, not no Chinese, no Vietcong, no Japanese. You my opposer when I want freedom. You my opposer when I want justice. You my opposer when I want equality. Want me to go somewhere and fight for you? You won’t even stand up for me right here in America, for my rights and my religious beliefs. You won’t even stand up for my right here at home. “

Upon refusing to be drafted, Ali transforms from an admired athlete to a convicted felon. Like Jack Johnson decades earlier, he is “unforgivably black.” He is stripped of his heavyweight titles and ends up penniless. In order to support himself and his family, he has to embark on a series of speeches at colleges across the country. When he finally “wins” the right to return to boxing, it’s based on a legal technicality by the U.S. Supreme Court. He is never officially “vindicated” in his decision to refuse to fight in Vietnam. The film underscores the roles available to black men in the 60s. They could be athletes, soldiers, or felons.

When the documentary officially opens in Chicago, I will invite some young black men to see it with me. I am curious about who they will “see” when they watch a larger-than-life Ali filling the screen. Will they see themselves in his brashness or not? Will they be more likely to identify with Jackie Robinson who appears in the film to denounce Ali’s decision against serving in Vietnam? Will they too be struck by Ali’s unapologetic blackness or will they see something else?

I am curious.

Stay tuned…